It’s not a joke; it’s a lab for collaboration. Listen to too much talk about innovation, and before long you’re bound to hear someone utter the “cross” word. It might be followed by “fertilization,” maybe “pollination,” perhaps even “disciplinary,” but the sharing of ideas with unlike-minded people is a hot topic, the holy grail of wannabe world-changers.

After all, the thinking goes, working with or alongside those who have different skills can lead to unconventional insights and ideas. And those are the ideas that actually have a shot at reinventing the status quo. And what self-respecting innovator isn’t interested in doing that?

There’s only one problem. Figuring out how to hire and house people with different skills is hard. If yours is a small company, however fervent your belief in the gospel of innovation, it’s difficult to justify hiring a neuroscientist if you’re trying to develop, you know, an app. Even larger companies, who crow about how they totally value the wisdom of mixing disciplines, can get stymied when it comes to organizing their employees. Like sits with like, and though cafeterias stocked with free food are intended to turboboost the “water cooler factor” of unexpected meetings and conversations, it can still be hard to quantify how often impromptu meetings lead to actual insights.

Certain labs or locations have become legendary over the years. The Bell Labs complex was filled with a hodgepodge of researchers, physicists and engineers delightedly pushing the boundaries of what was possible. MIT’s Building 20 was known as the “magical incubator” for its mix of legends and insights (its successor, the Frank Gehry-designed Stata Center, has notably been less successful in producing the same outcome). And now, some MIT Media Lab veterans are building their own space for experimentation and collaboration in a building on a busy street in downtown Brooklyn.

33 Flatbush Avenue is a seven-story building filled with creative people and enormous amounts of stuff, much of it collected by the building’s eccentric landlord, Al Attara. The top floor has been colonized by an eclectic group, a number of them MIT Media Lab veterans, with a few TED Fellows in the mix, all with very different areas of expertise. In one corner is costume designer Andrea Lauer; occupying another wall is musical robot builder Andy Cavatorta; designer and creative engineer Bill Washabaugh perches with his team in a corner by one of the windows, overlooked by a neon sign reading, ahem, “Go F*ck Yourself.” (“It’s aimed at myself, mainly,” he explains sheepishly.) Physicist and author Janna Levin (see her TED Talk, The sound the universe makes) has a curiously baroque space containing a writing desk and a few chaises longues. Biologists Ellen Jorgensen and TED Fellow Oliver Medvedik have a large but more contained space, perhaps advisable given their work at Genspace, the community biolab.

On the face of things, almost none of the assembled workers have anything in common — and that, says designer, inventor and another TED Fellow working here, James Patten, is precisely the point. “Everyone collaborates with everyone, whether formally or informally,” he said recently. “We’re very careful about who we add to the mix, to make sure we can all learn something new. Really, what we share is a sense of curiosity and a desire to be constantly learning.”

Patten himself works on projects that push the boundaries of both the expected and the easily understood. His own personal workspace certainly isn’t wildly interesting to look at; it’s just a desk surrounded by piles of unidentifiable stuff and shelves packed full of oddities (I did particularly enjoy the container marked “dismembered electronics”). But by the time you’ve stepped off the creaking elevator and circuitously picked your way over there, you’ve already been infected with a spirit of experimentation. It’s not glamorous, certainly not a place for germophobes, yet the space is imbued with a crackle of creativity and collaboration any organization would do well to mimic.

Other tenants on the seventh floor at 33 include designer and engineer Adam Lassy; designer and technologist Amanda Parkes; graphic designer and TED Fellow E. Roon Kang; media artist Kyle McDonald; programmer and artist Lauren McCarthy and artist and biologist Nurit Bar-shai. Figuring out who will do well in the space is a critical decision and one of the only formal processes the group has: potential new tenants give a 20-minute presentation of their work, followed by a discussion and Q&A. A two-thirds majority is needed to let someone join. “At its most amazing, there’s a real mix of people and projects in the space,” says Patten. “What it really comes down to is that we’re all constantly looking for interesting, unexpected connections and insights.”

It’s hard to describe, so we roped in photographer Ryan Lash to try and capture the spirit of a place. Take a look.

Downtown Brooklyn is where it’s at

It doesn’t look like much, but 33 Flatbush Avenue, in a drab part of downtown Brooklyn, is a hotbed of creativity and collaboration. Really.

A whole floor of mess

The seventh floor of 33 Flatbush Avenue, like most of the building, is crammed to the gills with… stuff. Some of it is supplied by tenants, much of it is stored there by landlord Al Attara. It’s not a place for germophobes, but somehow the place makes sense.

What to do when you need to construct a 90 foot window

The multi-tiled window hanging over this part of the space was a prototype for a piece installed at the Nature Research Center in Raleigh, North Carolina. The real thing is ten feet wide, 90 feet in length and made of 3,600 tiles of LCD glass. It represented a serious collaboration between many of the tenants at 33 Flatbush, who took over another floor of the building to manufacture it.

The name of the game: collaboration

“The theme of the space is that everyone collaborates with everyone,” says designer and inventor, James Patten. “That includes official collaborations, of course, but there are also constant informal moments where someone will help you figure something out or let you know if an idea is crazy.”

When software guys experiment with hardware

Entrepreneur, data scientist, and TED Fellow Jean-Baptiste Michel is more used to the virtual world of software and deep computer science. But even he has got in on the hardware design action. One of his first pieces, for which he tore apart an old-school clock, has pride of place on the wall behind his desk.

Artists play with pixels

Artist and designer Jamie Zigelbaum shows off Pixel, installed in the entryway of the seventh floor. “Everything these days is screens,” he explains. “We don’t think about what it means for all communication to be mediated by pixels, which are now this fundamental unit.” This piece, therefore, is a bodysize lightbox pixel; it glows more brightly when someone passes by and changes color on direct touch.

A chaotic, magical place to write

Astrophysicist, author and Columbia professor Janna Levin has two other offices in the city. She comes to this space to write. Yes, it’s a mess, she says, and yes, there’s a sense of chaos — and that’s precisely the point. “I have to have that hubbub. It’s a fascinating and magical place.”

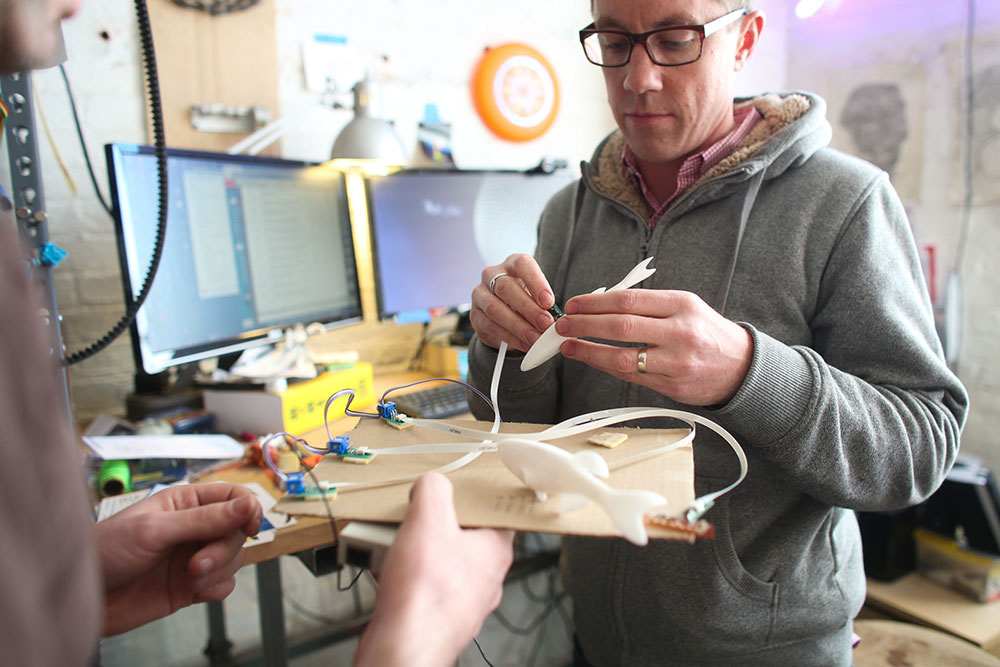

Informative, robotic fish fit for a hospital

Designer and engineer Bill Washabaugh and James Patten are currently collaborating on an interactive wall to be installed in a hospital in North Carolina. Circuits will be installed inside 475 fish that will be located on the wall; these will respond to touch and display digital information about a corresponding donor.

The one thing everyone really has in common: a love of sensible storage options

The tenants may not have much in common, work-wise, but they all clearly have charge cards at The Container Store. All the walls are stacked with plastic crates filled with crucial thingies and doodads.

The secret ingredient for success: The snack box

The crate of snacks is crucial for James Patten’s survival. “I’ll get into my work and won’t notice time passing,” he confesses. “Then I’ll take a phone call or something and realize that I’m totally out of it. But by then it’s already too late, so having a box of snacks right there is pretty helpful.”

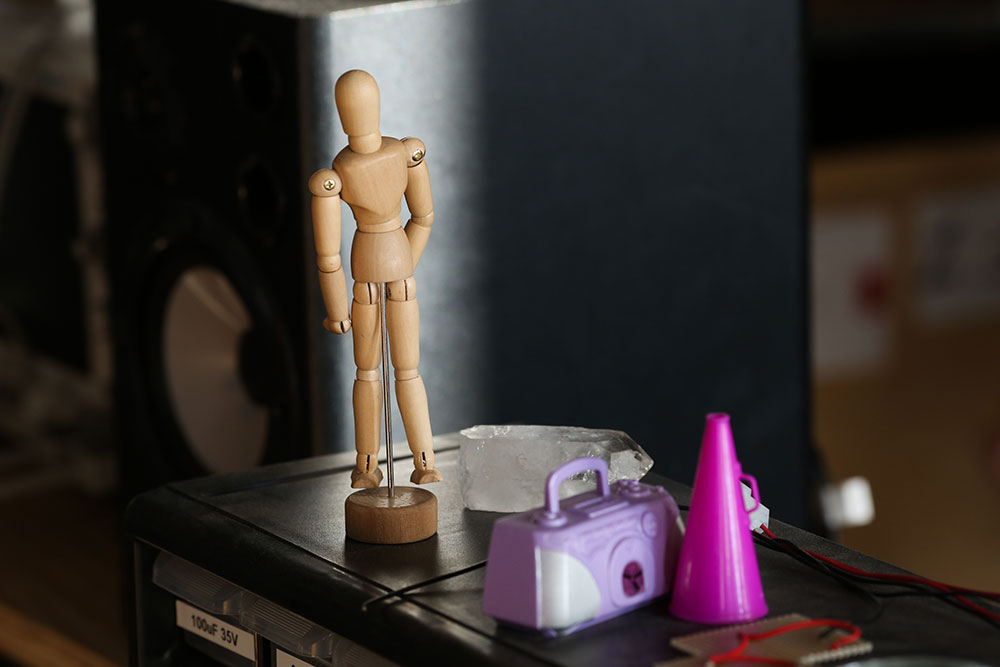

How to keep things interesting

A hoarder’s paradise, every surface on the floor is stacked with objects, from children’s toys to artist’s instruments or broken, filleted electronics. Much of it has been collected over the years by landlord Al Attara, who apparently keeps the nice furniture on the third floor. “All of the objects have history,” says James Patten. “Sometimes we’ll want to clear stuff out and it’ll turn out that a particular metal object was a prop in the first Die Hard film. It keeps things interesting.”

Photographs: Ryan Lash.