“The political and the sexual are intimate bedfellows,” says Shereen El Feki in her talk from TEDGlobal 2013. “That is true for all of us, no matter where we live and love.”

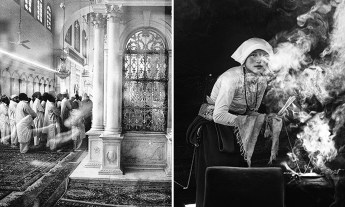

For five years, El Feki talked to people across Middle East about their bedroom behavior, and what she found over and over was a seemingly deep-rooted conservatism — in which any sex outside of heterosexual marriage is unacceptable. But as she shows, Arabic literature is rich with proof that the regional culture was once far more sexually open; erotic writing was produced even by religious scholars.

So what happened? El Feki points to the rise of religious conservatism starting in the 1970s — within the lifetimes of many people she interviewed. Such a rapid turnaround may seem improbable. But it happens all the time, and the past century offers many examples of societies that radically shifted their sexual attitudes. Below, the 20th century in five sexual revolutions.

Where: The United States

When: The 1920s

What changed: The Jazz Age in American life is mythologized as something of a decade-long party — and it isn’t a bad way of thinking of the economic and political factors that aligned to allow sexual expression at a level not imagined a decade before. In the rural, agriculturally dominated time that preceded it, a large traditional family was an economic asset — but by the ’20s, urbanization and industrialization had reached levels that allowed for fewer children, later marriage and more sexual freedom. Peace and prosperity after WWI called for celebration. Meanwhile, the long struggle for women’s right to vote had brought women out of the home and into the streets. But perhaps one of the most interesting things that made sexuality so visible in this time was the rise of the advertising industry, which brought sex appeal into everyday objects. In these prosperous times, not all goods were necessities — and manufacturers needed a means to market them. Earlier taboos on risqué public imagery gave way to a new truism — that sex sells.

Learn more about this shift »

Where: Germany

When: 1930s and ’40s

What changed: The rise of the Nazi party in the 1930s brought an abrupt shift in much of German culture, including in the areas of sex and gender. Although women had gained new freedoms during the post-WWI Weimar era, and sexuality had found much greater public expression, the Third Reich enacted an astoundingly rapid reversal of this “cultural decay,” as it was portrayed in propaganda. The Nazis’ primary focus was the procreation of a pure Aryan race – and their social policies emphasized a rigid family structure that focused on childbearing. Beginning in 1941, couples required a marriage clearance certificate to show that they had been properly screened for racial purity. Though the official ideology was of dutiful marriage, the Third Reich was in practice extremely permissive of premarital and extramarital relations that fell within the bounds of racial purity and heterosexuality. As an example, unwed teenage mothers once faced serious stigma but, by Nazi ideology, were considered superior to childless married women.

Learn more about this shift »

Where: The Western world

When: The 1960s

What changed: While the Arab world was becoming more conservative in its view of sexuality, the opposite was happening across the Western world. The Civil Rights, women’s liberation, and anti-war movements sent the status quo into tumult, as the tensions and uncertainty of the Cold War hung in the backdrop. Youth in Europe and America demanded a change from their parents’ reticence about sex, and challenged their behavioral taboos. The slogan “The personal is political” called for sexual matters to be a subject of international discussion. Free love and youthful rebellion is the image that the Sexual Revolution of the swinging ’60s often brings to mind – but equally important were the sudden changes that the new technology of the birth-control pill, which hit the market in 1960, brought into the bedroom. Before the Pill, fears of unwanted pregnancy had kept many women — both married and unmarried — from embracing their own sexual desires, but with better contraception came an unprecedented expression of sexuality.

Learn more about this change »

Where: China

When: The 1980s

What changed: Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong had made procreation to serve the state a tenet of his ideology. “The more people, the stronger we are,” he emphasized in his brutal Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. But after Mao, the Chinese government began to look for ways to control the country’s soaring population. A one-child policy was instituted in 1979 to address social, economic and environmental burdens –- but this required a populace that was knowledgeable about sex and contraception. Not an easy task, historically: Sexual conservatism had been a part of Neo-Confucianism from the 1100s on. Starting in 1980, books on sex began to be published where there had previously been none. Some were bestsellers. But as population control remained a pressing problem, the government recognized the further need for sex education in schools. Programs were introduced, first in high schools, and by 1988 the government had established sex education as standard middle school curriculum nationwide. Impressively, the need for family planning managed to outpace 900 years of deep cultural aversion to talking publicly about sex. After the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, a wave of political repression carried with it a return to more sexual restrictions, but sex education in China is on the rise today.

Learn more about this shift »

Where: South Africa

When: Post-apartheid – 1990s to the present

What’s changing: Generally lauded for its transition to a free democracy, post-apartheid South Africa bears a deep sexual scar — a higher incidence of rape and sexual violence than any peacetime country in the world. Compounding the problem, 10 percent of the population is infected with HIV. Some scholars view South Africa’s struggles with rape as a psychological legacy of years of institutionalized violence, both a backlash to oppression and a mirroring of it. President Jacob Zuma called for “a concerted campaign to end this scourge in our society,” and launched the Stop Rape campaign in 2013. Marches and demonstrations are held regularly in an effort to increase awareness, but many South Africans feel that only harsher punishment will act as a deterrent, and advocate a return to the death penalty, which was abolished in 1995. Weary from a decades-long culture of violence, the country is collectively seeking a way to break the cycle.

Learn more about this change»

Looking at the complexities of sex in the 20th century, a sketch emerges of the types of cultural and political changes that can ripple into every corner of a society — even its bedrooms. Far from being immutable and constant, sexual attitudes can shift with social change — for better or for worse.