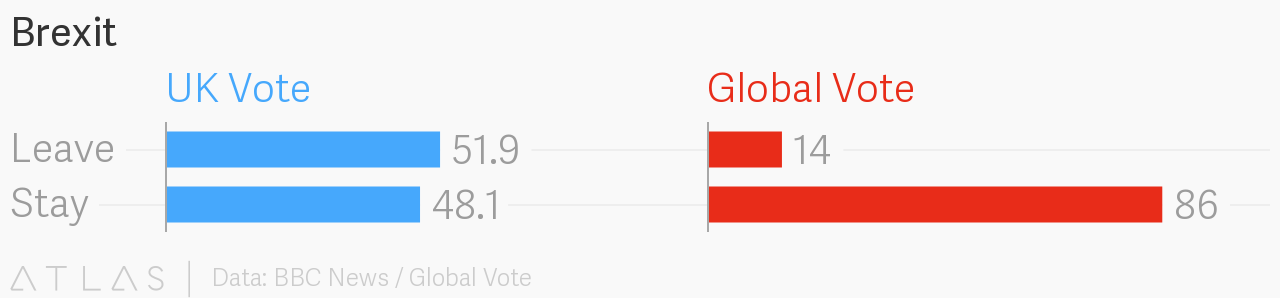

And Brexit wouldn’t have happened. At least that’s according to the Global Vote, an initiative which lets people vote in other country’s elections. Creator Simon Anholt tells us about the lessons learned from this real-life experiment in democracy.

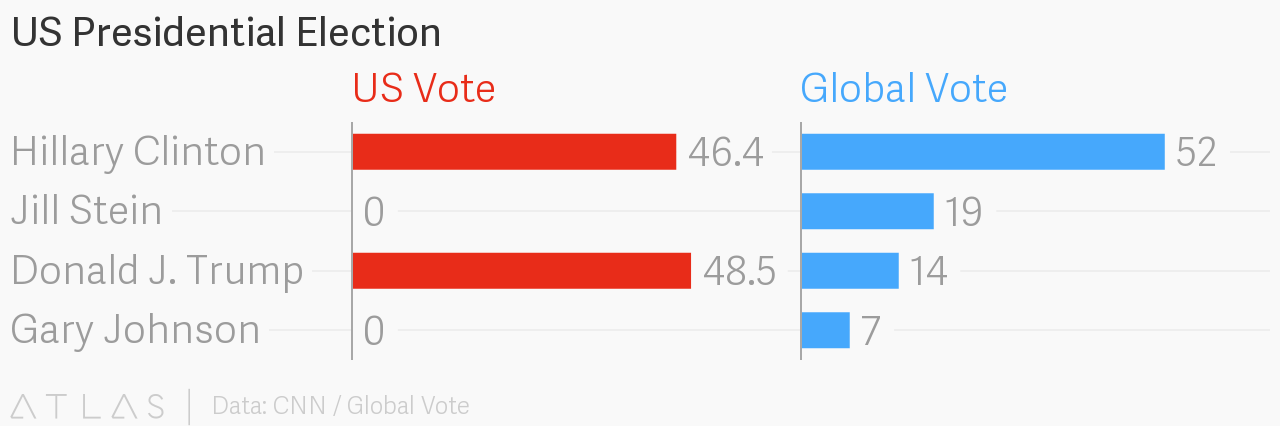

The results of the November 2016 election in America were as follows: Hillary Clinton, the Democratic candidate, won a landslide victory with 52 percent of the overall vote. Jill Stein, the Green candidate, came a distant second, with 19 percent. Donald J. Trump, the Republican candidate, was hot on her heels with 14 percent, and the remainder of the vote was shared by abstainers and Gary Johnson, the Libertarian candidate.

Contrary to what you might think, I am not living in a parallel universe. I live in the world, and that is how the world voted, according to the Global Vote. This initiative, which I launched in June 2016 as part of my Good Country project, lets anybody anywhere vote in the elections of other people’s countries.

Before I explain why I did this, allow me to explain why I didn’t. I did not want to interfere in the democratic processes of other countries. To prevent the Global Vote from influencing the outcomes of the elections we cover, our results are usually released after the electorate in each country has gone to the polls. And it wasn’t done for research purposes, either. This initiative is not designed to present a statistically accurate picture of world opinion, and in fact the results are strongly reflective of the internationalist mind-set of the people who take part.

And it’s not about domestic politics either. Through the Global Vote I’m asking people to consider: What are these candidates going to do for the rest of us, all around the world? We live, as you’re no doubt sick of hearing, in a globalized, hyperconnected, interdependent world where the decisions of other countries can have an effect on our lives no matter who we are, no matter where we live. Like the wings of the butterfly beating on one side of the Pacific that are said to create a storm on the other side, so it is with the planet today. Any country could produce the next Nelson Mandela — or the next Joseph Stalin. Its leader could make decisions that pollute the atmosphere and the oceans, which belong to all of us, or they could benefit the whole of humanity.

Yet in reality a limited number of people are eligible to vote for a country’s leaders, and then just a fraction of them actually go to the polls. For example, just 140 million Americans voted for president Trump, yet he has the power to affect all the other 7.36 billion of us on Earth. Similarly, in the Brexit referendum on whether to stay in or leave the EU, 33.5 million British people voted, but the outcome will have a significant impact on the lives of hundreds of millions of people in other nations. Huge decisions that affect all of us are being decided by relatively low numbers of people, which seems far from democratic.

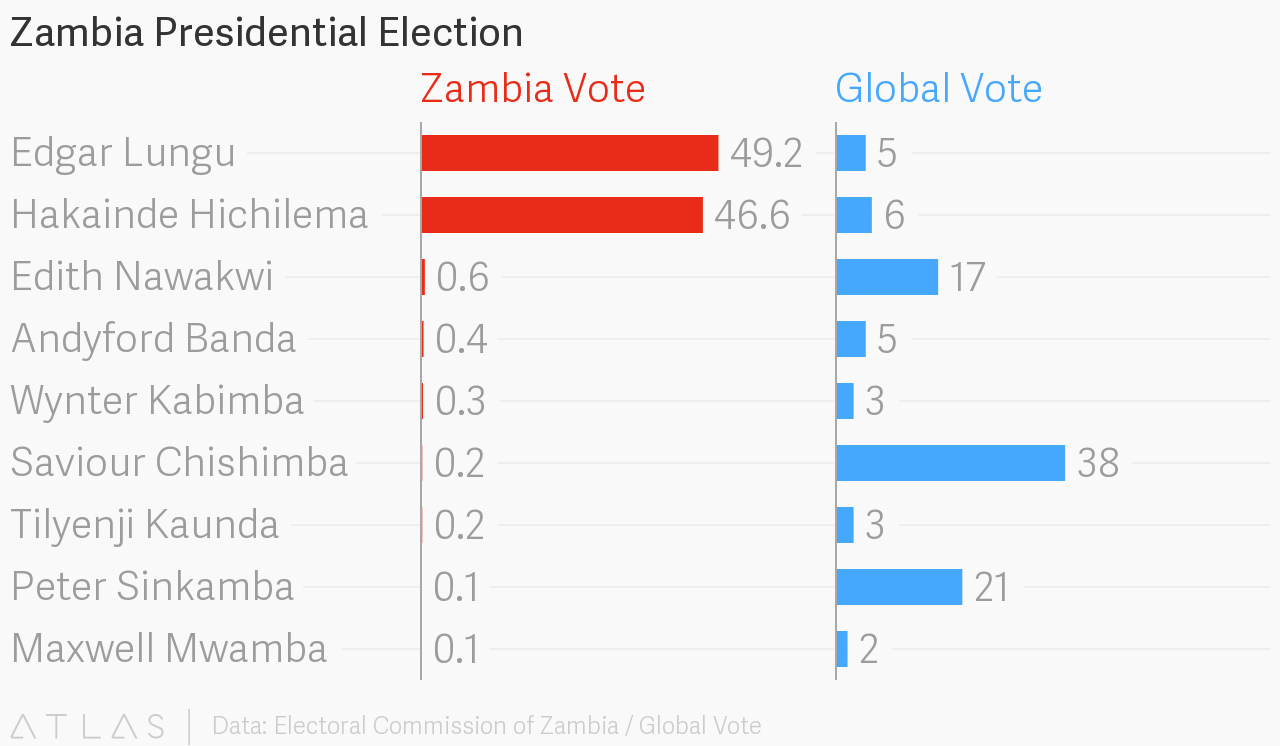

For every election we cover, the Global Vote sends the same two questions to all the candidates: 1) If you get elected, what are you going to do for the rest of us who live on the planet? 2) What is your vision for your country’s future in the world? Not every candidate answers, but more do every time. And some answer very enthusiastically. Saviour Chishimba was one of the candidates in the 2016 Zambian presidential election. His answers to those two questions were an 18-page dissertation on his view of Zambia’s role in the world and in the international community, which I posted on the Global Vote website. As you can see below, Saviour ended up winning our vote but scored a tiny fraction of votes in the actual election (although the results were hotly contested, the victory of Lungu was eventually confirmed by officials).

We humans currently face an enormous and growing number of gigantic challenges, like climate change, human rights abuses, mass migration, terrorism, economic chaos and the proliferation of nuclear weapons. All of these problems, some of which actually threaten to wipe us out, are global problems. No one country has the capability to tackle them alone, so nations must cooperate and collaborate to solve them. This may seem very obvious, yet leaders don’t do it nearly often enough. Most of the time, countries still behave like they were warring, selfish tribes, much as they’ve done since the nation-state was invented hundreds of years ago.

This has got to change. That shift will only happen if we ordinary people tell politicians that the culture has changed and they’ve got a new mandate. The old mandate was simple: if you’re in a position of power or authority, you’re responsible for your own people and your own tiny slice of territory. But today, every country’s leader has a dual mandate, which says you’re responsible for your own people — and for every other man, woman, child and animal on the planet. You’re responsible for your own slice of territory — and for every square mile of the Earth’s surface and the atmosphere above it. And if you don’t like that responsibility, you shouldn’t be in power. Candidates for all national elections should understand that when they win, they join the team that runs the planet.

Since the Global Vote launched, our voters have got it wrong nearly every single time — that is, the candidate they’ve chosen is seldom the one elected by the country’s citizens. To me, this confirms the necessity of the exercise, since it highlights the gulf between the way people vote in their own country and the way they’d vote if they were really considering humanity as a whole. It shows me how much progress we still have to make in motivating everyone — both voters and candidates — to think about improving the world we live in for ourselves, our children and our grandchildren.

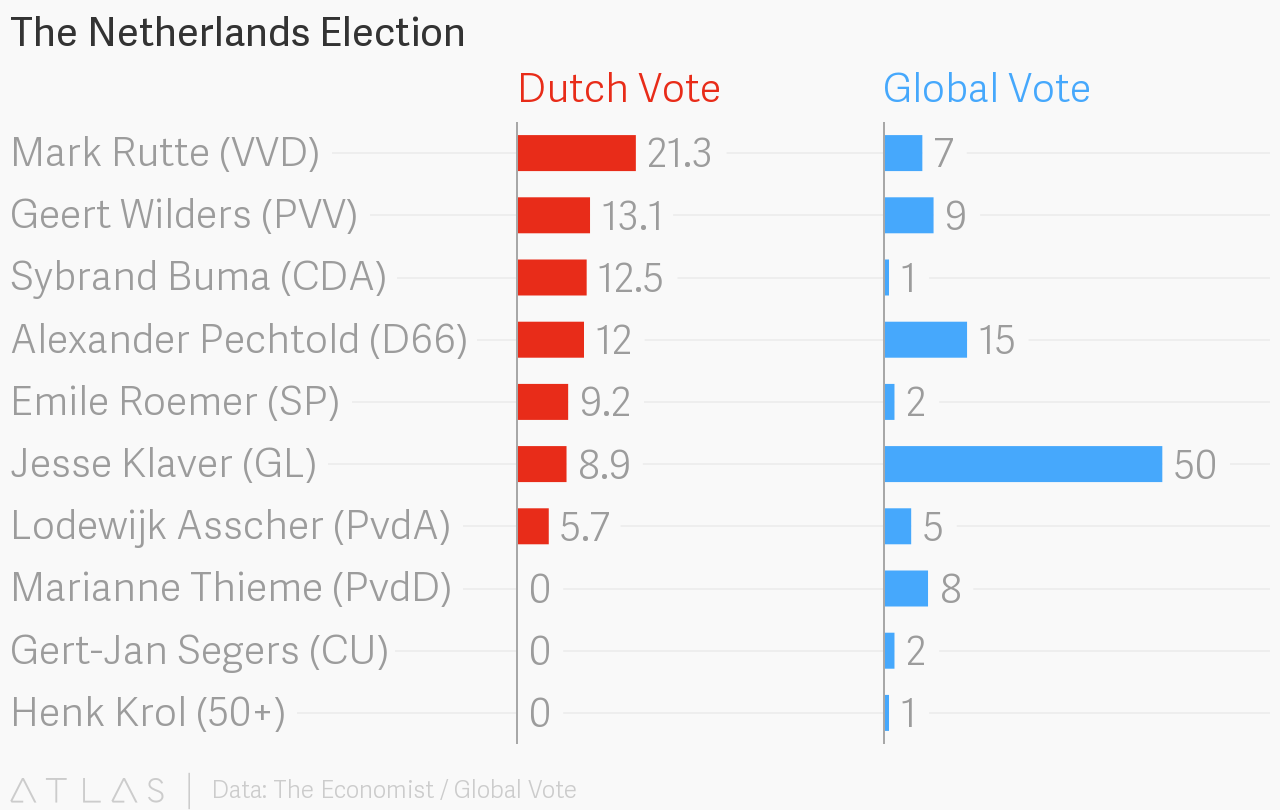

So far, we’ve had people from 146 countries participate, with anywhere from tens of thousands to 100,000 people (for the US presidential race) voting in each of our elections. I’m proud that the electorate is always relatively bipartisan. Yes, in our US election, Hillary Clinton received the largest number of votes but Trump did pretty well, too. In the Dutch election, the Green party candidate did well, but many people used the opportunity to vote for Geert Wilders, the populist candidate. Our candidate profiles are very carefully written to be neutral, objective and unbiased; it is particularly important that the Global Vote does not increase the existing political divisions. I don’t really care which candidate or which party wins — the important thing is that in doing it we’re demonstrating humanity’s essential interdependence.

The best thing about globalization is that it has the potential to stir up the world’s cultures and ideas to make us more creative, more effective and more productive than we have ever been before. The worst thing about globalization is how badly we have allowed it to be mismanaged in recent decades, enriching the few at the expense of the many. However, it would be a tragic error to try and stop globalization, and I don’t think we could even if we tried. And while we can’t reverse what has already happened, we can do better in the future by working together — across parties, across oceans and across national borders.