If English teacher (and citizen scientist) Hanny van Arkel can discover a rare astronomical object in her spare time, maybe you can too.

Hanny van Arkel was listening to a lot of Queen back in 2007. She wasn’t a big galaxy watcher at the time, but when Queen guitarist Brian May started promoting a citizen astronomy project called Galaxy Zoo, she decided to check it out. Then a few months later, she discovered a quasar ionization echo — and everything changed.

Galaxy Zoo allows anyone with an Internet connection to help scientists classify millions of galaxies. It’s fast, easy, and slightly addictive. (Watch scientist’s Chris Lintott’s TEDx Talk about the project here.) And Galaxy Zoo is just one of an ever-growing network of citizen science projects. For example, Floating Forests asks participants to identify clusters of kelp in photos of the world’s oceans. Elsewhere, Cyclone Center enlists people in tracing the patterns of tropical cyclones.

Citizen science is by no means a new concept. But the topic has gained prominence in scientific research lately — and the term was added to the Oxford English Dictionary this year.

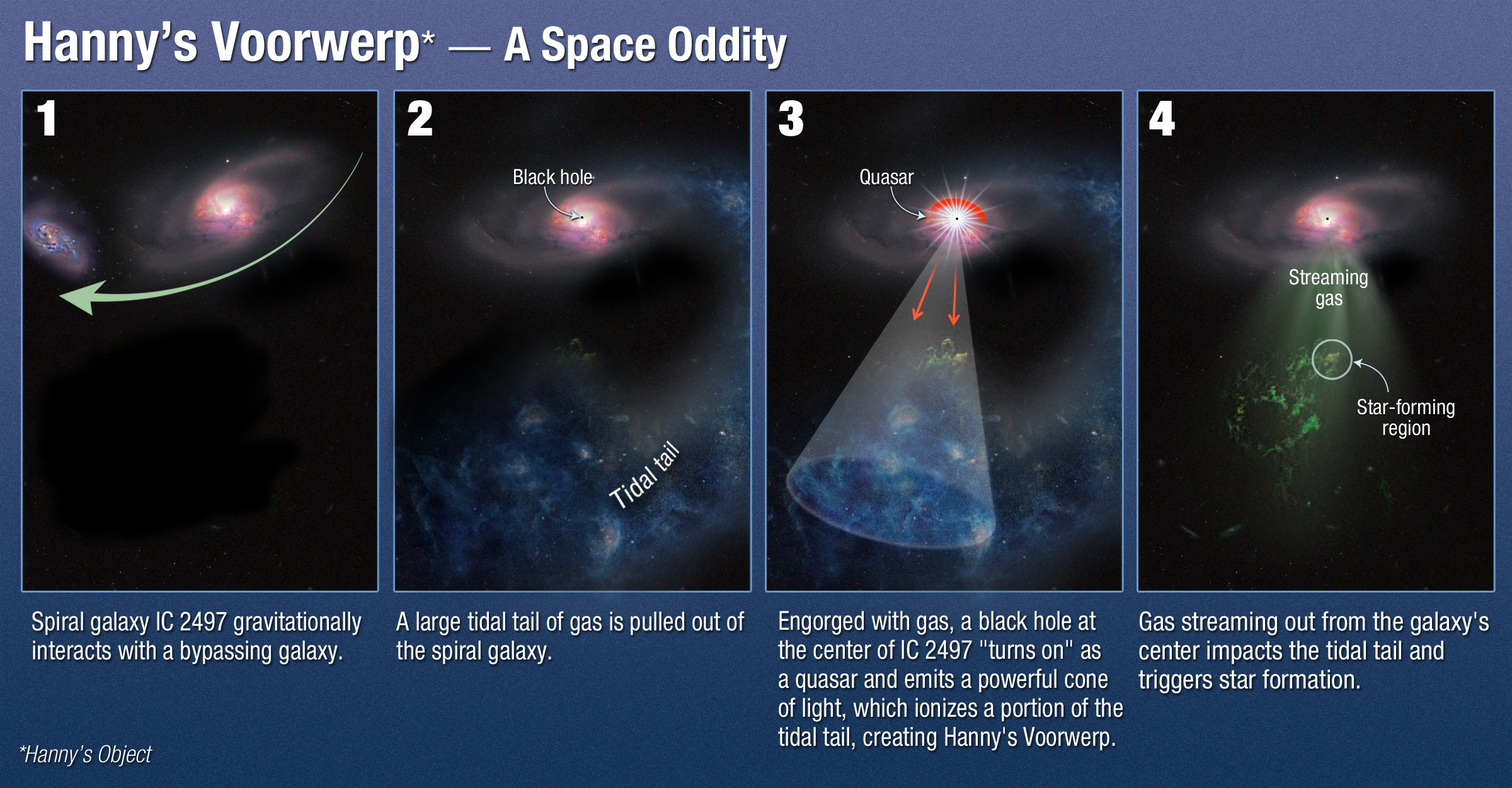

And with a superabundance of data available thanks to the increasing capabilities and sophistication of scientific technology, scientists need all the help they can get to pinpoint ideas worth noticing. A discovery like van Arkel’s — evidence of the lingering aftermath of a dead quasar, a quasar “light echo” — is rare even in the professional scientific community, and gives weight to the potential of projects such as Lintott’s.

The impact on van Arkel has been meaningful too. The English teacher has become an inadvertent science hero — even inspiring an astronomy comic book called Hanny and the Mystery of the Voorwerp.

We spoke to van Arkel about the story behind her discovery, the hullabaloo after, and how it feels to become an accidental astronomer. An edited transcript follows:

You speak about your discovery in your TEDxGhent talk, but for those who haven’t seen it, could you explain how it happened?

I found [Galaxy Zoo] through Queen’s guitarist Brian May. The project was made up by a friend of his, Chris Lintott. I wasn’t really into astronomy at that point; I was more into music, and Queen’s music, so that’s how I found out. Brian said that on Galaxy Zoo you could actually help scientific research and scientists, and I thought that sounded really cool. Even if you’re not a scientist yourself — they were actually asking citizens.

They had a data set of about a million pictures and these were already taken by a telescope and your task was to look through these pictures — they were beautiful images — and they outlined what you could find and what you had to click, so it wasn’t really difficult.

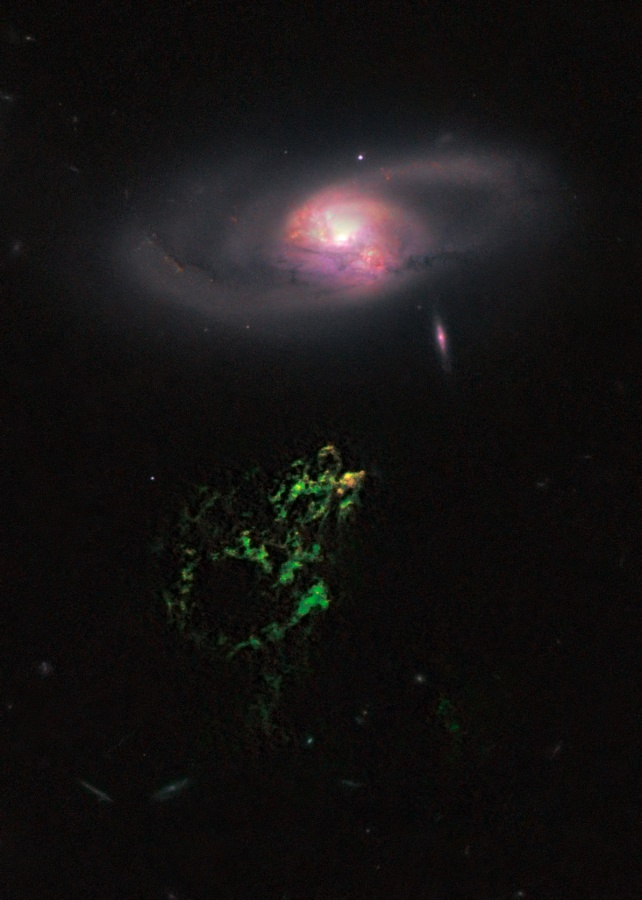

They were looking for different shapes and different galaxies and that sort of thing, but then I found something in one of these pictures that they hadn’t described previously in the tutorial, and that’s how I discovered Hanny’s Voorwerp.

What happened after that?

Well, first, not much, actually. There were lots of people classifying galaxies and asking Chris if they had discovered something, and I think my email was one of tens of thousands of emails that he got. I also mentioned it on the community forum, but people were just saying it looked weird, and nobody really had an answer. So it took a couple of months before [the scientists] thought, ‘We should really look into this,’ because they hadn’t seen anything like it in the whole set of pictures that they had. So they looked into it and about a year after the discovery they found out it was really something interesting and invited me onto the team to investigate this. That was really cool because I got to see how all of that works.

How did that work? What was that like for you?

So if you want to know more about an object like that, you need to have more information and look at it with different telescopes. And if you want to do that, you have to write a proposal, in which you say why you need to use these telescopes and that sort of thing. So my name was on these proposals. I think most of them were answered with a yes. Then that data comes in, they write papers about it, and I was involved in that process. I didn’t actually write anything — I just read along and asked, ‘What does that mean?’ and ‘What does that mean?’ But I’m officially a co-author (http://arxiv.org/abs/0906.5304), and I guess that’s how these things work. So that was fun.

Do you feel like you know more about astronomy now than when you started working on Galaxy Zoo?

Oh, definitely, yeah. I was always interested in astronomy — I just didn’t do anything with it. I learned a lot, and there was also this whole community of people doing it, too. I actually met some of my best friends through this project. So now we frequently do science-related things together. Or not science-related things.

And people turned you into a comic book, right?

Ah, yes, there was that, too! So we eventually found out what Hanny’s Voorwerp was and got a really cool picture from the Hubble space telescope. Then there was this American team of artists and astronomers that turned the whole discovery into a comic book. They asked for a couple of pictures from me, and then they turned me into this figure that says, ‘Oh, wow, what is this?’ and then I discover something. But it’s also good science. That was the aim of the comic book, to explain it to young people, and it looks really great.

Do you get a lot of people contacting you after reading about your story and asking you how they can discover things or what it’s like to be a citizen scientist?

Oh, yes, definitely. Over the years, I’ve met and spoken to so many people; sometimes I hear back from people from all these different places in the world, saying, ‘I found out about Galaxy Zoo because of your story,’ and that is the coolest thing.

It’s been seven years since your discovery … is there still hype?

Yes, I discovered it in 2007 and the press thing started in 2008. I think this is the good sort of press coverage, where you get to say, ‘This is a really cool project: Join in!’ and I can still have other things [going on in my life] as well.

Did you ever expect you’d make an astronomic discovery when you started working on Galaxy Zoo?

No (laughs), no, no. I mean, life has its surprises and this was certainly one of them.

Are you still teaching? Or has your life been taken over by the discovery?

I still manage to do both. It’s a good combination.

Featured image via iStock.