Here’s a riddle for you: A plane flew for five days and nights, staying airborne for 118 hours. But it didn’t use a single drop of fuel. How?

Because it’s solar-powered. Carrying some 17,000 solar cells, the Solar Impulse 2 plane ascends to 28,000 feet during the day to collect enough solar energy to charge the batteries attached to four electric motors. These then power the plane through the following 12 hours of darkness. At sunrise, the batteries start to recharge — and on it goes. The one-seater plane is the dream of adventurer Bertrand Piccard (TED Talk: My solar-powered adventure), one he designed to demonstrate the power and possibility of pollution-free travel. On July 1, 2015, the plane set a world record for the longest ever flight after a five-day, 5,100-mile trip from Japan to Hawaii. With Solar Impulse 2 grounded for repair right now (more on that below), Piccard got on the phone from Hawaii to share more about his big idea.

This solar flight isn’t about speed or airtime; it’s about showing there’s another way to travel. Solar planes themselves aren’t new; the first experimental crafts took flight in the 1970s. But Piccard’s plane is the first to effectively store energy, allowing for continuous flight. This isn’t about allowing extra long flights, either — after all, commercial planes can fly this distance in a shorter amount of time and with more passengers onboard. This is about showing what solar technology can do right now — with a view to thinking about what it might do as the technology improves.

World records only matter because they provide proof of concept. Solar Impulse 2 is halfway through an around-the-world flight, which began in Abu Dhabi in March. So far, the team has set two records for solar-powered flight and one general aviation world record. But Piccard stresses that he and his fellow pilot, André Borschberg, are not doing this for the glory. “The record was the proof that an airplane with no fuel can fly longer than any jet plane,” he says. “The goal is to encourage people to replace old, polluting technologies with new, clean technologies.”

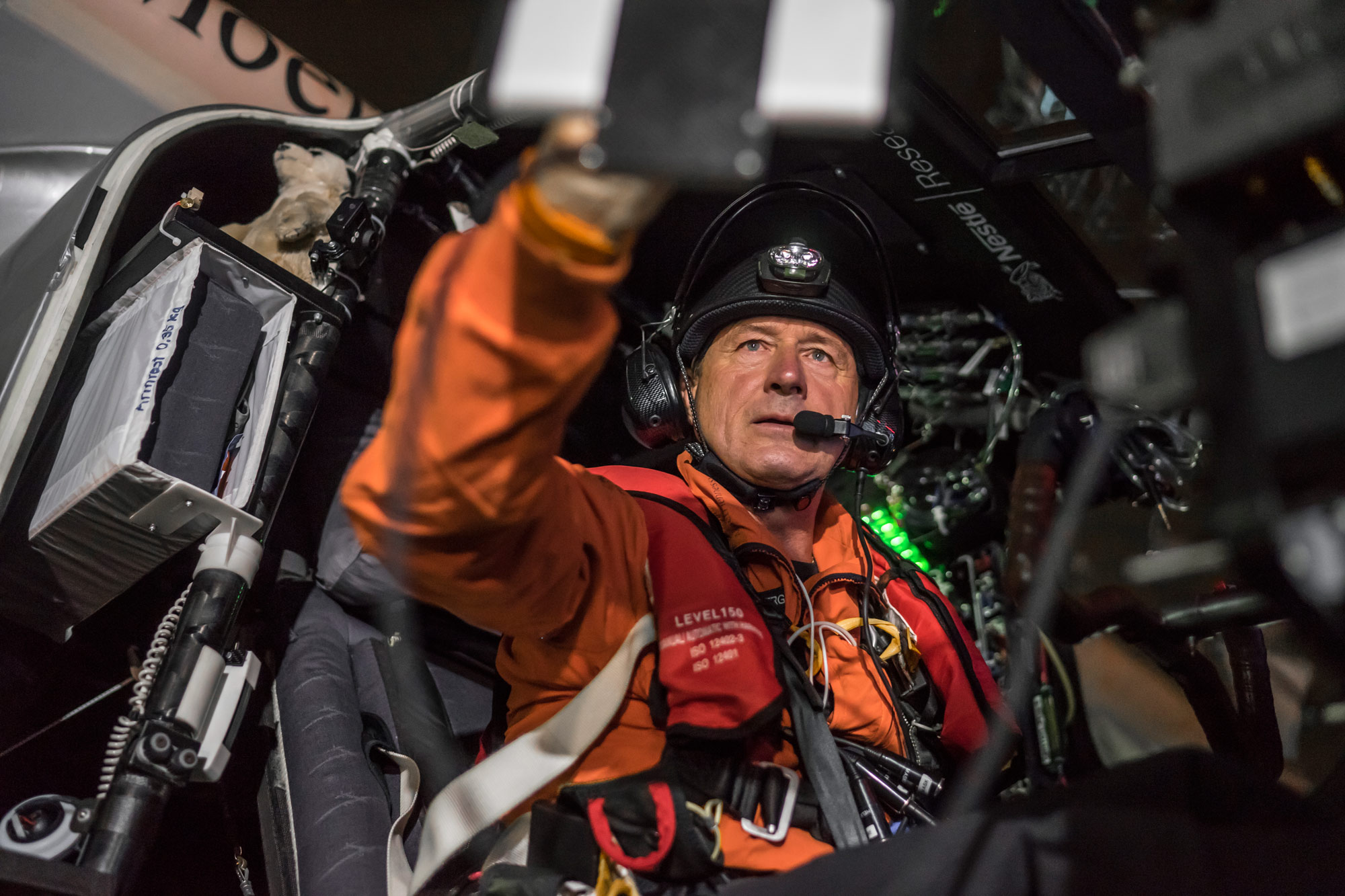

The hardest part of a long-haul solo flight is the isolation. Piccard and Borschberg trained extensively to live in the tiny cockpit — which is no bigger than the cab of a truck — for days at a time. There’s just enough room for the pilot, oxygen supplies and a week’s worth of food, specially prepared by Nestlé to withstand the range of temperatures in flight. The two make good use of autopilot and take long naps rather than settle in for a nighttime sleep. They do seated exercises to keep their muscles active; they meditate. “There’s a really nice moment when the sun rises,” says Piccard. “The sky is silver and the ground is black. Then you see a little line at the horizon. Suddenly, the sun pops out in a red flash. All the colors arrive on the Earth. The sun is up, and you feel all this energy coming again to the cells on the airplane. You say, ‘Wow, now that’s a new day coming.’”

When everything is new, unexpected things will happen. A team of 50 people works on the maintenance, communications and complicated logistics of flying an experimental plane among commercial airliners. “Everything is challenging because it’s new,” says Piccard. “Nobody did this before, so nobody can help. You just have to invent solutions.” The team ran up against an unforeseen challenge after Borschberg landed in Hawaii. “We overheated our batteries,” says Piccard. “The batteries are very efficient, but we had over-insulated them.” New batteries need to be tested extensively before the journey can continue — and that means the plane won’t take off again until next spring. (In September, the days become too short to cross an ocean safely.) While Piccard is disappointed about the delay, he sees it as just part of the process. “Fortunately, it’s not a race,” he says.

Adventure requires patience, persistence and leading by example. Piccard has been working on this project for 16 years. “When I started speaking about my vision of a plane with perpetual endurance, a lot of people — especially in the world of aviation — told me I was crazy,” says Piccard, whose first headline-grabbing journey was a nonstop, round-the-world balloon flight in 2009. “You shouldn’t always listen to people who tell you it won’t work.” Meanwhile, while the topic of clean energy typically makes people’s eyes glaze over, Piccard is committed to showing how it might work, not just talking about it. “I wanted to demonstrate that you can achieve impossible things with renewable energy,” he says. Already, their progress has inspired others: “An Indian minister said in an interview that he was inspired by Solar Impulse to make solar trains,” he says. “When we arrived in Hawaii, the governor said they have a goal to use 100% renewable energy by 2045, but now he realized they could be more ambitious.”

Pioneers shouldn’t go it alone. For Piccard, the key to any success for Solar Impulse came when he met Borschberg in 2003. “Everything I didn’t know how to do, he knew. Everything he didn’t know, I knew,” says Piccard. “André is a more experienced airplane pilot. I am the more experienced explorer.” The two decided who would fly which leg of the around-the-world flight accordingly — Piccard is flying over the Atlantic, the path of his hero Charles Lindbergh, while Borschberg’s experience was needed for the long haul over the Pacific. Piccard spent most of Borschberg’s record-breaking flight at Solar Impulse Mission Control Center in Monaco, and flew to Hawaii to greet his friend on the tarmac. It was an emotional moment. Says Piccard, “André told me, ‘Without you, I could never have done this adventure.’ And I told him, ‘Without you, my vision would have been a crazy dream.’”

Photos courtesy Solar Impulse.