As the sharing economy gains market share, it needs more support and structure to grow in the right directions.

For more than a decade, the sharing economy has functioned as a sort of benign, artsy cousin of the world’s corporate capitalist machine. Lately, though, the advances of Uber, Airbnb et al have brought much attention (and money) to the sector — and not everyone is happy about it. But one man believes that the real drama of the sharing economy is yet to come — and has the power to revolutionize work and transform culture.

In his new book The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism, published this week by MIT Press, Arun Sundararajan sketches out two scenarios for the future of work. In one outlook, growing numbers of Americans make money by leasing out their homes, skills or cars on digital platforms. Joining the haphazard world of self-employment, they become “disenfranchised drones,” cut off from salaries, benefits and legal protections and scrambling for opportunities and financial security.

In the other scenario, growing numbers of Americans turn to the same digitally organized marketplaces to become “empowered entrepreneurs.” Joining the liberating world of self-employment, they have high job satisfaction and a healthy work/life balance.

Which will it be? Sundararajan, a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business, sees enough value in the sharing economy — today’s networked, person-to-person exchanges of goods and services — to be an optimist. What’s more, he says, the potential advantages are not just commercial but can make us a more connected and trusting society. But he warns that the road to a happy outcome involves careful choices along the way. Regulations, whether by government or peers, will have to ensure that sharing-economy platforms operate fairly and safely alongside conventional businesses. New policies and funding models must give independent workers the insurance, retirement benefits, paid leave and other safeguards that have long been attached to full-time employment.

Digital technologies are creating an unstoppable revolution.

“We are at the early stages of a fundamental shift in how we organize economic activity,” Sundararajan said, speaking from his office at NYU. At the same time, he points out that the sharing economy isn’t new. In 1900, more than 40 percent of the paid United States workforce was self-employed, largely as farm hands and day laborers but also as small business owners like tradespeople and shopkeepers. By 1960,as workers embraced the job security and benefits offered by manufacturing and management jobs, the number of self-employed had dropped below 15 percent. So today’s model is in some ways a return to an older way of working.

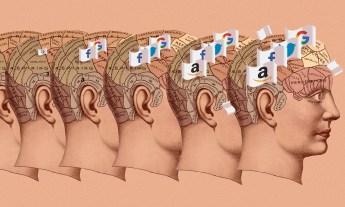

What is different, of course, is that sharing-economy participants now transact their business over vast networks with a speed and precision that allows them to make efficient use of idle resources like parked cars, spare rooms and spare time. Digital technologies are crucial here, to pinpoint and serve customers efficiently. In a sense, digital technologies transform everyday physical objects into transmittable data that expands the scope of what can be exchanged, fueling economic growth. Books, record albums, furniture, cash—all that was solid melts into code, downloaded from personal computers, reconstituted by devices like 3D printers, or zipping perpetually from server to server.

Thanks to the ever-growing power and agility of networks, computers and smartphones, we have seen the sharing economy evolve beyond goods sold on eBay and Etsy. Today, it includes services distributed through TaskRabbit, investment opportunities made possible on the micro-lending site Kiva, independent self-regulating currency operations in the form of Bitcoin. In the near future, Sundararajan believes, energy, healthcare and commercial real estate will also be exchanged through person-to-person markets. We might buy surplus power stored on an improved battery. We might seek a health-care worker in our neighborhoods to stitch up a laceration. We might rent office space from a workshare.

The rewards of the sharing economy are not only economic. Digital technologies are further responsible for establishing the most crucial component of the sharing economy: trust. It is one thing to depend on eBay for the prompt delivery of goods that meet your expectations — it is another to turn over your home to strangers through Airbnb. No sharing platform will work unless participants are convinced that they are dealing with people who are competent, well meaning and true to their identities (and not parading around under false ones). Sundararajan attributes the explosion of the sharing economy to a “digital trust infrastructure” made up of many kinds of assurances, from online reviews and social media pages to the mere act of holding a government-issued ID card up to a camera to prove one’s identity.

If the future of work is to be happy, however, independent contractors will have to be guaranteed the same labor protections and comforts as their full-time peers.

As we place ourselves with increasing confidence in vulnerable situations — stepping into a stranger’s car, handing house keys to an outsider — we build a more trusting society. Simply venturing into other spheres restores interpersonal connections that have been lost through market capitalism. “Economic exchange has become excessively impersonal,” Sundararajan says. We are separated from a cab driver by a partition and credit card machine, but we sit next to a Lyft driver. We drop a hotel’s white towels on the bathroom floor for the housekeeper to pick up, but carefully fold and hang the colorful towels in our Airbnb rentals, thinking about their owners. “A lot of the appeal of the sharing economy is that people feel happy connecting to other human beings as part of daily activity,” Sundararajan believes. That’s true for both sides of the exchange.

On some sharing platforms, workers also find sympathy for perceived injustices that were overlooked in traditional work environments. “We have paid so much more attention to the plight of Uber drivers than taxi drivers,” Sundararajan says. Domestic workers, who for decades have failed to receive labor protections, may find their collective voice as they connect with peers on sites like TaskRabbit and Handy.

But the economic advantages are nothing to sneeze at. Greater efficiency goes hand in hand with the goodwill these platforms generate. The creativity and variety generated by the sharing economy (1.5 million Etsy sellers, to cite just one example) boost innovation and quality, improvements that stimulate consumption and promote new marketplaces. “Our findings have consistently suggested that workers can generally expect to earn more per hour getting their freelance assignments through a digital labor market than by seeking it through traditional channels,” Sundararajan writes.

As more workers become micro-entrepreneurs and micro-venture capitalists, wealth can be distributed across a much broader population. The book notes, for instance, that most of the real estate owned by more than a million Airbnb hosts would otherwise be concentrated in hotel chains. “If a larger fraction of the population owns the means of production, that will naturally reduce income inequality,” Sundararajan suggests.

Benefits should not accrue only to those who are full-time employees. If the future of work is to be happy, however, independent contractors will have to be guaranteed the same labor protections and comforts as their full-time peers. The system in which freelance workers pay double Social Security benefits while getting neither 401(k) contributions nor paid time off is an artifact of the 20th century, when traditional social safety nets were woven and labor unions rose to balance the power between full-time workers and management. The Sharing Economy describes several models for funding benefits for the self-employed, including the idea, now being considered in Finland, of guaranteeing a fixed monthly income to every working adult. While this is not such a radical way of redistributing taxes as it may seem, Sundararajan believes a system with contributions from both the government and the sharing platforms themselves would be a more realistic path in the US, at least in the short term.

“We are at a critical stage of policy choice and have to pay attention to make sure the right choices are made,” Sundararajan says. The very meanings of the terms “employee” and “independent contractor” have blurred, as has the idea of what actually constitutes work. “In today’s economy, being employed or unemployed is becoming increasingly difficult to measure as microentrepreneurship, multiple gigs, freelance work and fluid self-employment muddle traditional definitions and measures,” he writes. The growth of the sharing economy will not only force new classifications of employment but will stimulate conversations about using yardsticks other than GDP to evaluate growth and prosperity. Leisure time, education and access to basic services like healthcare could (and maybe should) all be factors.

Still, many uncertainties remain about the future of work. The practice of outsourcing jobs overseas and developing machines that can perform even specialized human tasks casts a pall. And even while technology connects people, it also fosters isolation at home with Netflix streaming and Seamless food deliveries.

Even so, Sundararajan remains bullish. If the playing field were level in terms of benefits for full-time workers and independent contractors, there would be no contest between the two. Being the one holding the reins, he says, “is fundamentally empowering to the individual.”