Amy Cuddy’s TED Talk, Your body language shapes who you are, has millions of views for a reason — everyone who watched it understood a little bit more about themselves. But the flip side of her research is equally fascinating — how we can understand others through the body language they, consciously or unconsciously, choose to use. Back during the last U.S. presidential election in 2012, our writer Ben Lillie sat down to ask Dr. Cuddy: Can we use your research to understand the people who want to be the next President of the US? (Read the full interview here). As America swings into the 2016 season, here are four key insights on how to judge candidates during a presidential debate. (And one tip on how to win it.)

We judge candidates (and everyone) on two primary dimensions: their warmth, and their power. We ask: do I like this person (warmth/trustworthiness)? And do I respect this person (power/competence)? As Cuddy says, “We’re constantly — although usually unintentionally — sending nonverbal signals that people use to judge how warm or powerful we are, and we’re also constantly judging how warm and powerful they are based on their nonverbal signals. So that’s what I’m looking for when I’m watching politicians: what their body language says — or is trying to say — about their power and their warmth.”

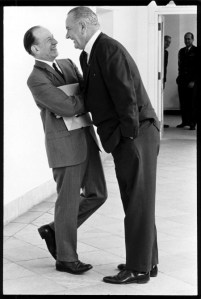

Debate drinking game: Spot the power pose. Watching debates is a guilty pleasure for this expert on body language. “If you look for power poses, you’ll start noticing lots of them,” she says. “Pay attention to how expansive the candidates’ postures are: Are they using wide, open, strong, defined gestures? Are they standing with their feet apart? Do they have their hands resting on the outsides of the podium, to spread out a bit more? Puffing out their chests a bit? Racing to be the first one to reach out and initiate the handshake? And how much space are they taking up? Are they trying to occupy each other’s space, by doing something like grabbing their opponent’s arm during the handshake? Or doing even more aggressive things, like walking toward their opponent and really getting up in their space, LBJ-style? It’s also interesting to track the nonverbals throughout the debate — is the stronger debater becoming even more expansive and the weaker debater beginning to close up a bit, even in subtle ways, like how much they lift or lower their chin?”

Most politicians are past masters at displaying power. Warmth, not so much. “I don’t see a lot of politicians in the national spotlight who are really struggling to communicate power, mostly because they focus so obsessively on appearing the strongest, the most alpha,” she says. “But what these politicians are much more likely to struggle with, or just neglect to do altogether, is communicate warmth and trustworthiness.” She studied one Congressional candidate who had a habit of smiling at precisely the wrong time: when he was criticizing someone else. “And so there he’d be, talking about some very negative thing … while smiling. People don’t like that; it comes across as snarky and self-satisfied. Voters were like, ‘Sure, he’s smart, but I don’t like the guy.’ I have to say, he really is a truly nice person — he cared so much about what he was doing — but he just didn’t know how to get that across.” You can see it in this video clip from a past presidential debate: “There’s a John McCain clip where he’s saying that he’s going to ‘follow Osama Bin Laden to the gates of hell.’ And then at the very end of this aggressive, fierce statement, he breaks into this painfully fake smile. You can tell that someone, maybe a coach, maybe an advisor, said, ‘You need to smile more, Senator.’ And it’s as if whenever he paused, he’d remember: ‘must smile more, must smile more,’ but it was often at the most inopportune times. It looks terribly awkward, and it makes people really uncomfortable.”

Why warmth matters when you’re choosing a future leader — or hoping to become one. Debates are a chance for candidates to stand up and be judged. And, Cuddy says, “People judge trustworthiness before competence. They make inferences of trustworthiness and warmth before competence and power. And the reason is that it answers the question, ‘Is this person friend or foe?’ With a stranger, you first want to know what their intentions are toward you, and then you want to know, can they carry out those intentions? You have to connect with people and build trust before you can influence or lead them. Trust is the conduit for influence; it’s the medium through which ideas travel. If they don’t trust you, your ideas are just dead in the water. If they trust you, they’re open and they can hear what you’re offering. Having the best idea is worth nothing if people don’t trust you.”

So, candidates, keep the power posing for backstage. Onstage, show us that you care. As Cuddy says, “It’s really important to separate what you do before the interaction from what you do during the interaction. You want to feel powerful going in — but that does not equal dominant or alpha. You want to feel that you have the power to bring your full, spirited self to the situation, stripped of the fears and inhibitions that might typically hold you back. I believe this allows you not just to be stronger, but also to be more open and trusting. But nonverbally displaying power during the interaction — now that’s another thing. I’m definitely not an advocate, as I think I’ve made clear by now, of going in and power-posing in front of people in order to intimidate them or something. Yes, use strong, open nonverbals: Don’t slouch or make yourself small, and be as big as you can comfortably be. But don’t use alpha cowboy moves, like sitting with legs apart and your arm draped over the back of the chair next to you. That can directly undermine the trust you need to build.”

Illustration by Emily Pidgeon/TED.