Probably not. But if we want a future where more of those jobs are decent and well-paying, we — and our institutions — need to rise to its challenge, says economist David Autor.

Here’s a startling fact: in the 45 years since the introduction of the automated teller machine, those vending machines that dispense cash, the number of human bank tellers employed in the United States has roughly doubled, from about a quarter of a million in 1970 to a half a million today, with 100,000 added since the year 2000. These facts, revealed in Boston University economist James Bessen’s recent book Learning by Doing, raise an intriguing question: What are all those tellers doing, and why hasn’t automation eliminated their employment by now?

If you think about it, many of the great inventions of the last 200 years were designed to replace human labor. Tractors were developed to substitute mechanical power for human physical toil. Assembly lines were engineered to replace inconsistent human handiwork with machine perfection. Computers were programmed to swap out error-prone, inconsistent human calculation with digital perfection. These inventions have worked: We no longer dig ditches by hand, pound tools out of wrought iron or do bookkeeping using actual books. And yet, the fraction of US adults employed in the labor market is higher now in 2016 than it was in 1890, and it’s risen in just about every decade in the intervening 125 years. This poses a paradox. Our machines increasingly do our work for us. But the reason there are still so many jobs can be explained by two fundamental economic principles: one has to do with human genius and creativity; and the other has to do with human insatiability, or greed, if you like.

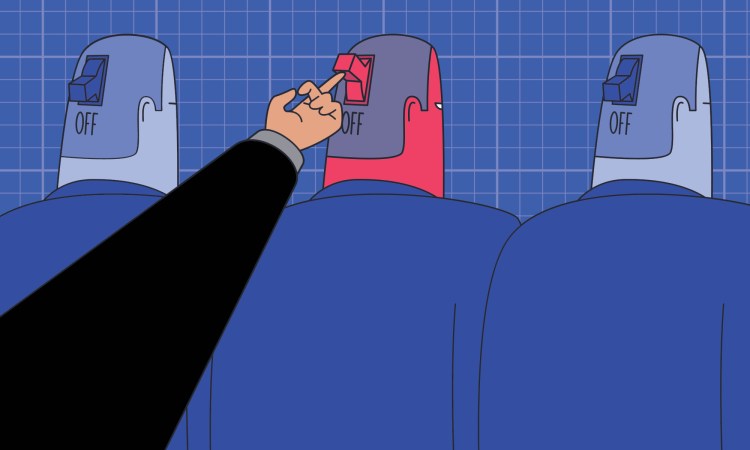

Automating a subset of a position’s tasks doesn’t make the other ones unnecessary — in fact, it makes them more important.

I’ll call the first economic principle the O-ring principle, and it determines the type of work that we do. ATMs ended up having two countervailing effects on bank teller employment. As you’d expect, they replaced a lot of teller tasks, and the number of tellers per branch fell by about one-third. But banks quickly discovered ATMs also made it cheaper to open new branches, so the number of bank branches increased by about 40 percent in the same time period. The net result was more branches and more tellers. However, these tellers were doing somewhat different work. As their routine, cash-handling tasks receded, they became less like checkout clerks and more like salespeople, forging relationships with customers, solving problems and introducing them to new products like credit cards, loans and investments. They were doing a more cognitively demanding job.

In general, automating some subset of a position’s tasks doesn’t make the other ones unnecessary — in fact, it makes them more important and increases their economic value. Let me give you a stark example. In 1986, the space shuttle Challenger exploded and crashed down to Earth less than two minutes after takeoff. The cause of that crash, it turned out, was an inexpensive rubber O-ring in the booster rocket that had frozen on the launchpad the night before and failed catastrophically moments after takeoff. In this multibillion-dollar enterprise, that simple rubber O-ring made the difference between mission success and the death of seven astronauts. Building on this powerful metaphor, Harvard economist Michael Kremer developed the O-ring production function.

The O-ring production function conceives of work as a series of interlocking steps, links in a chain, and every one of those links must hold for the mission to succeed. If any of them fails, the mission, product or service comes crashing down. This precarious situation has a surprisingly positive implication, which is that improvements in the reliability of any one link in the chain increase the value of improving any of the other links. Conversely, if most of the links are brittle and prone to breakage, the fact that your link is not that reliable is not that important because something else will probably break anyway. But as all the other links become robust and reliable, the importance of each link becomes more essential. The reason the O-ring was critical to space shuttle Challenger is because everything else worked perfectly.

In much of the work that we do, we are the O-rings. Yes, ATMs could do certain cash-handling tasks faster and better than tellers, but that didn’t make human tellers superfluous. Instead, it increased the importance of their problem-solving skills and their relationships with customers. The same principle applies if we’re building a building, if we’re diagnosing and caring for a patient, or if we’re teaching a roomful of high schoolers. As our tools improve, technology magnifies our leverage and increases the importance of our expertise, judgment and creativity.

Material abundance has never eliminated perceived scarcity.

The second principle is the never-get-enough principle, and it determines how many jobs there actually are. Once we create a technology that makes us sufficiently productive at something, we’ve basically worked our way out of a job. In 1900, 40 percent of all US employment was on farms; today, it’s less than two percent. This isn’t because we’re eating less or because there are fewer Americans. A century of productivity growth in farming means that now, a couple of million farmers can feed a nation of 320 million. It’s amazing progress, but it also means there are only so many O-ring jobs left in farming. So technology can eliminate jobs, and farming is only one example. But what’s true about a single product, service or industry has never been true about the economy as a whole.

Many of the industries in which we now work — health and medicine, finance and insurance, electronics and computing — were tiny or barely existent a century ago. Many of the products that we purchase, like air conditioners, sport utility vehicles, computers and mobile devices, were unattainably expensive, or just hadn’t been invented back then. As automation frees our time and increases the scope of what is possible, we invent new products, new ideas and new services that command our attention, occupy our time and spur consumption. While you may think some of these are frivolous — extreme yoga, adventure tourism, Pokémon GO — the fact is, people desire them and they’re willing to work hard to pay for them. In 2015, the average worker who wanted to attain the average living standard of 1915 could do so by working just 17 weeks a year, or one third of the time. But most people don’t choose to do that. They’re willing to work hard to harvest the technological bounty that is available to them. Material abundance has never eliminated perceived scarcity, or, in the words of economist Thorstein Veblen, invention is the mother of necessity.

However, this doesn’t mean we’ll always have plenty of jobs. Automation creates wealth by allowing us to do more work in less time, but there is no economic law which mandates we will use our wealth well, and this is something worth worrying about. Consider two countries: Norway and Saudi Arabia. While both are oil-rich nations, they haven’t used that wealth equally well to foster human prosperity. Norway is a thriving democracy. By and large, its citizens work and play well together, and it typically ranks between no. 1 and no. 4 in rankings of national happiness. Saudi Arabia, by contrast, is an absolute monarchy in which many citizens lack a path for personal advancement, and it’s typically ranked 35th among nations in happiness, which is low for such a wealthy nation. (By way of comparison, the US is typically ranked around 12th or 13th.) The difference between the two countries is not their wealth and it’s not their technology — it’s their institutions. Norway has invested to build a society with opportunity and economic mobility. Saudi Arabia has raised living standards while frustrating many other human strivings.

We’ve faced equally momentous economic transformations in the past, and we’ve come through them successfully.

The challenge today is not that we’re running out of work — the US has added 14 million jobs since the 2008 recession — but that many of those jobs are not good jobs. What’s more, many citizens cannot qualify for the good jobs that are being created. Employment growth in the US and in much of the developed world looks like a barbell with increasing poundage on either end of the bar. On the one hand, you have high-education, high-wage jobs, like doctors and nurses, programmers and engineers, and marketing and sales managers. Employment and employment growth are robust in those professions. Similarly, growth is robust in many low-skill, low-education jobs, like food service, cleaning, security and home-health work. At the same time, employment is shrinking in many middle-education, middle-wage, middle-class jobs, like blue-collar production and operative positions and white-collar clerical and sales positions.

The reasons behind the contracting middle are not mysterious — many middle-skill jobs use well-understood rules and procedures that increasingly can be codified in software and executed by computers. The challenge this phenomenon creates is that it knocks out rungs in the economic ladder, shrinks the size of the middle class, and threatens to make us a more stratified society, divided between highly paid, highly educated professionals doing interesting work and low-wage employees whose primary responsibility is to see to the comfort and health of the affluent. That’s not my vision of progress, and I doubt that it’s many people’s.

The encouraging news is we’ve faced equally momentous economic transformations in the past, and we’ve come through them successfully. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, when automation eliminated vast numbers of agricultural jobs, the farm states faced a threat of mass unemployment, a generation of youth no longer needed to work in the fields but not prepared for industry. The country took the radical step of requiring that the entire youth population remain in school and continue their education until they were 16. This was called the high school movement, and it was a radically expensive thing to do. Not only did America have to invest in schools, but kids couldn’t work at jobs. It also turned out to be one of the best investments the US made in the 20th century, giving us the most skilled, the most flexible and the most productive workforce in the world. To see how well this worked, imagine taking the labor force of 1899 and bringing them into the present. Despite their strong bodies and good characters, many of them would lack the basic literacy and numeracy skills to do all but the most mundane jobs. Many of them would be unemployable.

What this highlights is the primacy of our institutions, most especially our schools, in allowing us to reap the harvest of our technological prosperity. Clearly, we can still get this wrong. If the US had not invested in its schools and in its skills a century ago with the high school movement, we’d be a less prosperous, less mobile and probably a lot less happy society. But it’s equally foolish to say our future will be decided by the machines or the market. It will be decided by us and by our institutions.

Some would argue that this time is different from what happened 100 years ago, and of course, it is different — every time is different. On many occasions in the last two centuries, scholars and activists have raised the alarm that we were running out of work and making ourselves obsolete. There were the Luddites in the early 1800s; US Secretary of Labor James Davis in the mid-1920s; Nobel-winning economist Wassily Leontief in 1982; and the many researchers, pundits, technologists and media figures today.

But the predictions of our present-day self-proclaimed oracles strike me as arrogant. In effect, they’re saying, “If I can’t think of what people will do for work in the future, then you, me and our kids aren’t going to think of it, either.” While I can’t tell you what people are going to do for work 100 years from now, the future doesn’t hinge on my imagination. If I were a farmer in Iowa in the year 1900 and an economist from the 21st century teleported down and said, “Hey, guess what, farmer, in the next hundred years, agricultural employment will drop to two percent due to rising productivity. What do you think the other 38 percent of workers are going to do?” I wouldn’t have said, “Oh, we got this. We’ll do app development, radiological medicine, yoga instruction, Bitmoji.” I wouldn’t have had a clue. But I hope I would have said, “Wow, a 95 percent reduction in farm employment with no shortage of food. That’s an amazing amount of progress. I hope that humanity finds something remarkable to do with all of that prosperity.”

Of course, rising to our challenges will not be automatic, costless or easy. But it is feasible, and thanks to our amazing productivity, we’re rich and can afford to invest in ourselves and in our children, just as America did 100 years ago. Arguably, we can’t afford not to.