How do you walk 500 miles? Extreme hiker Sarah Marquis explains how pain gives way to pleasure during an epic trek through the wilderness.

Sarah Marquis will call her parents to let her know she’s coming to visit — and she’ll be there in a week. That’s because her preferred mode of transport is on foot, and from her house in the Swiss Alps to her folks up north is a seven-day, cross-country hike. She wouldn’t choose to arrive a moment sooner. “Walking is the perfect speed for us,” says Marquis, who believes that modern-day commuters, hurtling through the world at unnatural speeds, have lost a profound connection to their surroundings. Marquis has made a career out of walking extreme distances, up to 12,000 miles in one trip, and sharing her stories of endurance in a series of books and lectures. She describes her most recent expedition, a 500-mile, three-month-long trek through Western Australia’s Kimberley National Park.

The first step is simply being present. In June 2015, Marquis was dropped off by helicopter at the mouth of the Berkeley River, the starting point of her journey, in a desolate patch of “crocodile country” roughly 60 miles from the nearest town. “I had this amazing feeling of freedom mixed with fear, mixed with, ‘I have to get out of here, now,’” she says. For 10 days, she walked with a singular purpose to dodge crocodiles and reach her destination as quickly as possible. Gradually, her fear gave way to a growing awareness of her surroundings. “You start to notice little things in the landscape, like a nice little patch of grass that’s greener than the rest,” she says. The process is not so much a conscious struggle with fear, she says, as it is as a shift in focus to tune into strange, new sensations.

When you walk everywhere, every sense is heightened and attuned to unexpected pleasures. Marquis can pick up the trace scent of water from a distance of several kilometers. “The air is usually saturated with tannin from the plants, the trees and the grass, but as soon as you get closer to the water, the air becomes really sharp,” she says. “It’s difficult to explain.” As her sense of smell sharpened, so too did her palate — on this trip she had a ration of 100 grams of flour a day, and then she had to find all other food along the way. So the edible flowers of the Grevillea tree, for instance, were a sugary treat, until the nectar struck her as too sweet and cloying. Meanwhile, the bland heart of the Pandanus spiralis palm tree became one of her favorite wild delicacies. “It’s like eating a cookie,” she says. “Really. Now that I’m talking about it, I can feel the taste in my mouth.”

Pain doesn’t fade away. It vanishes all at once. “You have to go through this horrific, difficult time,” Marquis says of extreme hiking. Every muscle and joint ached as her body adjusted to the strain of walking for 12 hours, upwards of 20 kilometers a day. There was no knowing when the pain would end. On a previous 3-year trek across Asia and Australia, Marquis says, the pain persisted for six months. Inevitably, though, it vanishes. “It’s like you walk through a door,” Marquis says. “You open the door, and it’s all fine after that, and you don’t feel the pain in your body.”

The true goal is a journey of the mind. Marquis insists that the key to enjoying a long walk is to avoid the temptation to distract yourself with a book, an iPod or any other machine-made diversion. Neither should you resort to spinning stories or songs in your head. Any conscious attempt to fend off boredom is futile, and she’s seen her fellow hikers suffer the consequences. “They fight with themselves all the way, just to avoid this journey of the mind,” she says. The goal is not to retreat into your mind, but to unleash it on your surroundings. “It’s an out-of-body experience, but you have to believe in yourself and step into the unknown. The exploration is not only happening outside. It’s constant work, a humbling road, but it’s so worth it.”

Boredom is inconceivable. “There is this big open, wide, amazing space around you,” she says, “It entertains me all the way, and I’m fascinated with nearly everything.” Because anything from an insect under a leaf to the color of a rock becomes an object of fascination, each minute is as exciting as the last. “People often ask me, ‘What was the highlight of your trip?’” she says. “But it’s a stupid question, because there really is no such thing.”

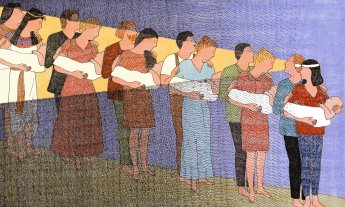

Photo illustration by Sacha Vega/TED.