Behavioral economist Wendy de la Rosa regretted how much she was spending, but felt like she couldn’t stop. She shares the lifehack that got her spending under control — and two other money-saving tricks.

We all know that saving is important and something that we should be doing more of. Overall, though, most of us seem to be doing less and less of it. Is it just because we’re dumb when it comes to money or lack willpower?

No — the amount we save largely depends on the environmental cues around us. I’m a behavioral economist and the cofounder of Common Cents Lab, a research lab based at Duke University that uses behavioral science to help Americans improve their financial well-being.

Here’s an example of what I mean. In 2017, we ran a study in which the subjects — people who received SNAP food benefits — were divided into two groups. With one group, we showed them their benefits income on a monthly basis. For the other group, we showed them their benefits income on a weekly basis.

We found the people who saw their income on a weekly basis budgeted better than the ones who saw their income on a monthly basis. While the amount of money was exactly the same, we changed the environment — here, the timing — in which they understood their income.

Why did this help? Most SNAP benefits are distributed in a lump sum once a month. From social science, we know that receiving lump sums can create a “windfall” mindset, which leads to a false sense of security and hinders our ability to budget. As a result, we’re more likely to misallocate our funds.

The windfall effect is something we’re all susceptible to. Many of us feel more flush on the days we get paid — and thus end up spending more — compared to the last day of our pay cycle. You can harness the effect of our study by thinking about your salary in weekly amounts rather than yearly or monthly.

Here are three other ways that you can help yourself make smarter money decisions:

1. Take aim at your small, frequent purchases.

At Common Cents Labs, we’ve run a few different studies and asked people to tell us which purchases they most regret. After bank overdraft fees, the number-one regretted purchase was … eating out. It’s a frequent purchase that many of us make regularly, but, savings-wise, it’s death by a thousand cuts. A coffee here, a burrito there — it all adds up and decreases our savings.

When I lived in New York City, my most-regretted purchase was on ride-sharing apps. One month, when I looked at my expenses, I saw that I’d spent over $2,000 on them. That was more than my monthly rent!

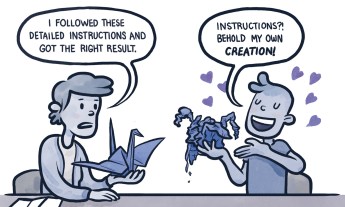

I vowed to make a change, and the next month, when I looked at my expenses, I saw that I spent … $2,000! Despite my pledge, there was no change. Why? The information I’d gotten about my spending wasn’t enough to change my behavior, even though I really wanted to. It backfired because I did nothing to change my environment.

I decided to do two things. The first: I unlinked my credit card from the ride-sharing apps and I linked them to a debit card which had $300. If I needed more than that, I would have to go through the process of adding more money to the card or switching to a different card. From research, I knew that every click and every barrier affects our behavior and we’re less likely to try to overcome them.

The second: I gave myself a limit. We humans aren’t machines; we don’t carry around a spreadsheet in our brains, adding up what we’re spending, and comparing the amount to what we had wanted to spend. However, our brains are very good at focusing on simpler numbers, like counting how many times we’ve done something. So I told myself that I’d use ride-sharing apps only 3 times a week or 12 times a month. This was a huge reduction from my typical behavior — I’d been using them 50 to 75 times a month. Imposing a quota forced me to ration my travels.

Take a look at the expenses in your own life, and identify your most regretted purchases. Then, modify your environment to make it harder for you to spend. Borrow my tactics, and you can also get creative. If the thing that you keep buying is from a website, delete your payment information and address from the site and browser so you have to enter them every single time you buy. If you use an app to buy it — but it can be purchased without one — de-install the app from your phone. Instead of a debit card with a set amount, you could withdraw that amount in cash from the ATM and restrict yourself to using that.

2. Commit your best self — a.k.a. your future self — to saving.

Fundamentally, we humans think about ourselves in two different ways: there’s our present self and there’s our future self. We have an optimistic view of our future selves. Our future selves are the one who will work out, who will call our parents more, who will save for retirement. And one reason we don’t save is because we believe that our future selves are going to take care of it. We forget that our future selves are actually the same as our present selves and that our present selves need to start doing this good thing now.

At Common Cents Labs, we know one of the best times for people to save is when they get their tax refund. So we ran a study. With the first group, we texted people in early February — in the hopes that it was before they filed their tax returns — and asked them: “If you get a tax refund, what percentage would you like to save?” Now this is a hard question to answer. The people didn’t necessarily know if they’d receive a tax refund or how much it would be, but we asked the question anyway and we told them that their answer would be binding.

With the second group, we asked people right after they had filed their returns and received their refund: “What percentage would you like to save?”Just as with the other group, their answer would be binding.

Here’s what happened. The second group of people — the ones who just received their tax refund — said they wanted to save about 17 percent of it. But the first group of people — the ones who hadn’t even filed their taxes and gotten a refund — said they wanted to save about 27 percent, 10 percentage points higher.

Why the difference? We think it’s because we asked the first group to answer on behalf of their future selves, and of course, their future selves can save more money. We can tap into that same power by thinking about how we can commit our future selves to save money. For example, we could sign up for an app — such as Qapital, Digit or Chime — that lets people make savings decisions in advance.

However, it’s important that the commitment have real consequences — this cannot be an empty pledge that we can easily get out of. The decision we make today for our future selves must matter. In our tax savings experiment, users made a real commitment when they told us how much they planned to save; they knew their refund money would be directly transferred into their savings accounts.

3. Use transition moments to your advantage.

In 2017, we did an experiment with a website that helps older adults to share their housing. We ran two different ads on social media that were targeted to the same population of 64-year-olds. With one group, the ad said: “Hey, you’re getting older. Are you ready for retirement? House sharing can help.” With the second group, the ad got more specific and said: “You’re 64 turning 65. Are you ready for retirement? House sharing can help.”

What we were doing with the second group was highlighting that a transition is happening in people’s lives. And we saw people’s click-through rates on the ad — and ultimately their sign-up rates — increase as a result.

In psychology, we call this the “fresh start effect.” Think about it: whether it’s the start of a new year or a new season, your motivation to act increases. Put this to work in your own life by placing a meeting invite on your calendar the day after your next birthday. Identify the one financial thing you most want to do — maybe it’s opening a retirement savings account or consolidating your student loans or credit-card debt. And make this one invite that you can’t cancel or move around.

This article was adapted from TED’s “The Way We Work” series. Watch it here:

Other videos in the series examine office romance, happiness on the job, the side-hustle revolution, building a company that people like working for, working from home, and bringing your whole self to the workplace. Go here to see them all.