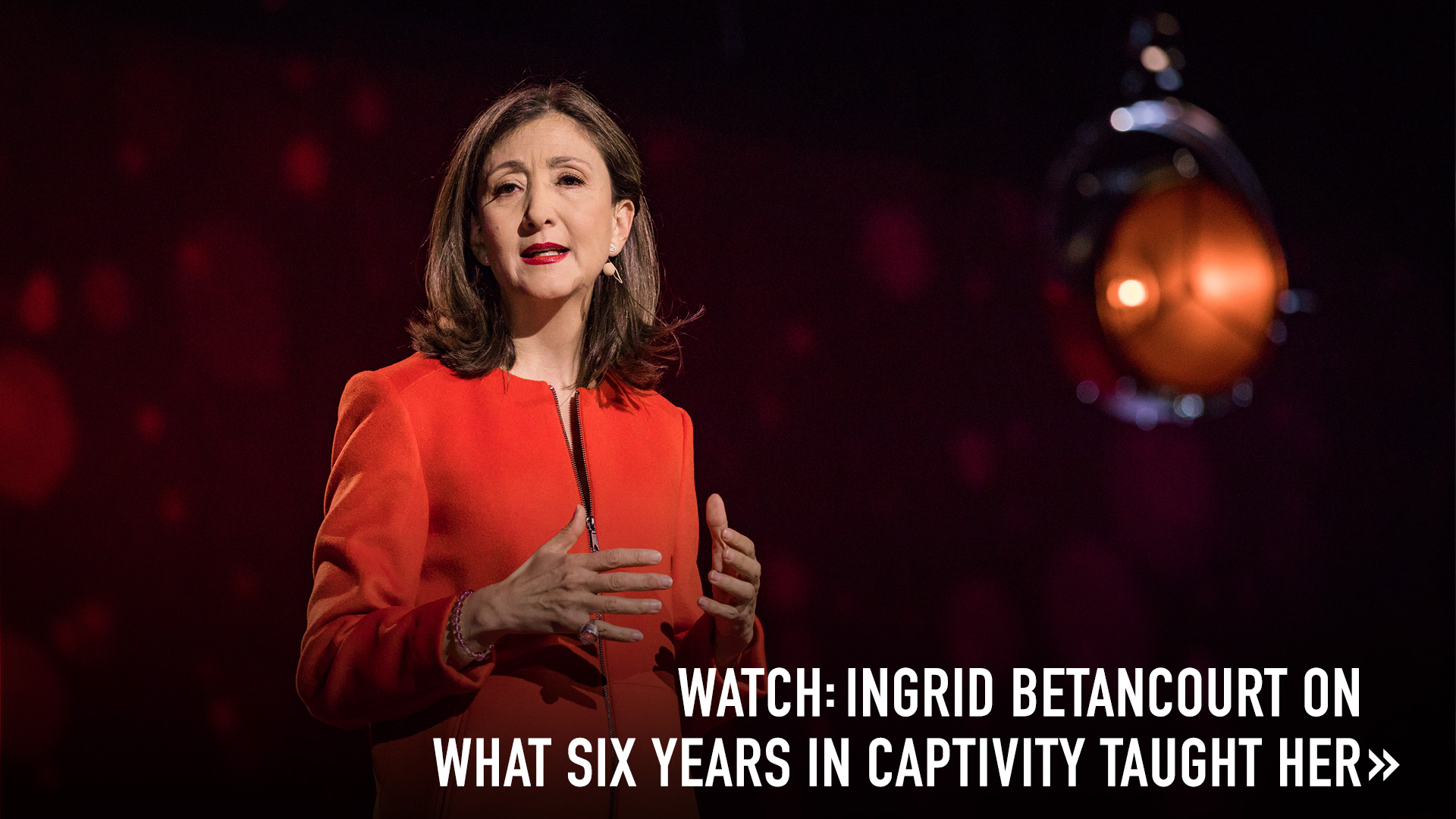

In 2002, Ingrid Betancourt was campaigning to become president of Colombia when she was kidnapped by guerillas. She was held in the jungle for six years. With fear her constant companion, she learned how to use it and grow.

The first time I felt fear I was 41 years old. People have always said I was brave. When I was little, I’d climb the highest tree, and I’d approach any animal fearlessly. I liked challenges. My father used to say, “Good steel can withstand any temperature.”

And when I entered into politics in Colombia, I thought I’d be able to withstand anything. I wanted to end corruption; I wanted to cut ties between politicians and drug traffickers. The first time I was elected, it was because I called out corrupt and untouchable politicians by name. I also called out the president for his ties to the cartels.

That’s when the threats started. As a result, one morning I had to send my very young children, hidden in the French ambassador’s armored car, to the airport to stay out of the country. Days later, I was the victim of an attack but I emerged unharmed. And the following year, the Colombian people elected me with the highest number of votes. I thought people applauded me because I was brave. I, too, thought I was brave.

But I wasn’t. I had simply never experienced true fear.

I went to sleep in fear every night — cold sweats, shakes, stomach aches — but worse than that was what was happening to my mind.

That changed on February 23, 2002. At the time, I was promoting my campaign agenda as a presidential candidate when I was detained by a group of armed men. They were wearing uniforms with military garments. I looked at their boots — they were rubber, and I knew that the Colombian army wore leather boots — so I knew these were FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) guerrillas.

From that point on, everything happened very quickly. The commando leader ordered us to stop the vehicle. Meanwhile, one of his men stepped on an anti-personnel mine and flew through the air. He landed, sitting upright, in front of me. We made eye contact, and it was then that the young man understood: his rubber boot with his leg still in it had landed far away. He started screaming like crazy.

The truth is, I felt — as I feel right now, because I’m reliving these emotions — I felt at that moment that something inside of me was breaking and that I was being infected with his fear. My mind went blank and couldn’t think; it was paralyzed. When I finally reacted, I said to myself, “They’re going to kill me, and I didn’t say goodbye to my children.” As they took me into the deepest depths of the jungle, the FARC soldiers announced that if the government didn’t negotiate, they’d kill me. And I knew that the government wouldn’t negotiate.

I was suffering enormous behavioral changes, and it wasn’t just paranoia. It was also the urge to kill.

I went to sleep in fear every night — cold sweats, shakes, stomach aches, insomnia. But worse than that was what was happening to my mind, because my memory was being erased: all the phone numbers, addresses, names of very dear people, even significant life events. So, I began to doubt myself, to doubt my mental health. And with doubt came desperation, and with desperation came depression. I was suffering enormous behavioral changes, and it wasn’t just paranoia in moments of panic. It was distrust, it was hatred, and it was also the urge to kill.

This I realized when my captors had me chained by the neck to a tree. They kept me outside that day, during a tropical downpour. I remember feeling an urgent need to use the bathroom.

“Whatever you have to do, you’ll do in front of me, bitch!” the guard screamed at me.

And I decided at that moment to kill him. For days, I was planning, trying to find the right moment, the right way to do it, filled with hatred and fear. Suddenly, I rose up, snapped out of it, and thought, “I’m not going to become one of them. I’m not going to become an assassin. I still have enough freedom to decide who I want to be.”

Beyond my fear I felt the need to defend my identity, to not let them turn me into a thing or a number.

That’s when I learned that fear had brought me face to face with myself. It forced me to align my energies, and I learned that facing fear could become a pathway to growth. When I think back, I’m able to identify the three steps I took to do it.

The first was to be guided by principles. I realized that in the midst of panic and my mental block, if I followed my principles, I acted correctly. I remember the first night in the concentration camp that the guerrillas had built in the middle of the jungle. It had 12-foot-high bars, barbed wire, lookouts in the four corners, and armed men pointing guns at us 24 hours a day. The first morning, some men arrived and yelled: “Count off! Count off!”

My fellow hostages woke up, startled, and began to identify themselves in numbered sequence. But when it was my turn, I said, “Ingrid Betancourt. If you want to know if I’m here, call me by my name.”

The guards’ fury was nothing compared to that of the other hostages because they were scared — we were all scared –and they were afraid that, because of me, they would be punished. Beyond my fear I felt the need to defend my identity, to not let them turn me into a thing or a number. That was one of my principles: to defend what I considered to be human dignity.

The jungle is like a different planet — a world of shadows, bugs, jaguars, anacondas. But none of these animals did us as much harm as the humans.

But make no mistake. The guerrillas had been kidnapping for years, and they had developed a technique to break us, to defeat us and to divide us. So the second step was to learn how to build trust and unite.

The jungle is like a different planet. It’s a world of shadows, of rain, with the hum of millions of bugs, like majiña ants and bullet ants. While I was in the jungle, I didn’t stop scratching for a single day. Of course, there were also jaguars, tarantulas, scorpions, anacondas — I once came face to face with a 24-foot-long anaconda that could have swallowed me in one bite.

Still, I want to tell you that none of these animals did us as much harm as the humans. The guerrillas terrorized us. They spread rumors. Among the hostages, they sparked betrayals, jealousy, resentment and mistrust. The first time I escaped for a long time was with Lucho. Lucho had been a hostage for two years longer than me. We decided to tie ourselves up with ropes and lower ourselves into the dark water full of piranhas and alligators. During the day, we would hide in the mangroves, and at night, we would get in the water, swim, and let the current carry us. That went on for several days, until Lucho became sick. A diabetic, he fell into a diabetic coma, and the guerrillas captured us.

But after having lived through that with Lucho and after having faced fear together, united, nothing — not punishment, not violence — could ever again divide us. At the same time, all of the guerrillas’ manipulation was so damaging to us that even today, tensions linger among some of the hostages I was held with. It was passed down from all of the poison that the guerrillas created.

“Ingrid, you know I don’t believe in God,” said Pincho. I told him, “God doesn’t care. He’ll still help you.”

The third step was to learn how to develop faith — it is very important to me. Jhon Frank Pinchao was a police officer who had been a hostage for more than eight years. He was famous for being the biggest scaredy-cat of us all. But Pincho — I called him “Pincho” — had decided he wanted to escape, and he asked me to help him. By that point, I basically had a master’s degree in escape attempts.

We were delayed because, first, Pincho had to learn how to swim, and we had to carry out our preparations in total secrecy. When we finally had everything ready, Pincho came up to me and said, “Ingrid, suppose I’m in the jungle, and I go around and around in circles, and I can’t find the way out. What do I do?”

“Pincho, you grab a phone, and you call the man upstairs,” I said.

“Ingrid, you know I don’t believe in God,” he said.

I told him, “God doesn’t care. He’ll still help you.”

That evening, it rained all night. The following morning, the camp woke up to a big commotion because Pincho had fled. The guerrillas made us dismantle the camp, and we started marching. During the march, the head guerrilla told us that Pincho had died, and they’d found his remains eaten by an anaconda. Seventeen days passed — and believe me, I counted them, because they were torture for me — and on the seventeenth day, the news exploded from the radio: Pincho was free and obviously alive.

And this was the first thing he said: “I know my fellow hostages are listening. Ingrid, I did what you told me. I called the man upstairs, and he sent me the patrol that rescued me from the jungle.”

That was an extraordinary moment. Obviously, fear is contagious. But faith is, too. Faith isn’t rational or emotional. Faith is an exercise of the will. It is the discipline of the will. It’s what allows us to transform everything that we are — our weaknesses and our frailties — into strength and power. It’s truly a transformation. It’s what gives us the strength to stand up in the face of fear, look above it, and see beyond it. I know we all need to connect with that strength we have inside of us during the times when there’s a storm raging around our boat.

Yes, fear is part of the human condition, but it’s also the guide by which each of us builds our identity and our personality.

Many, many, many, many years passed before I could return to my house. But when they took us, handcuffed, into the helicopter that finally brought us out of the jungle, everything happened as quickly as when they had kidnapped me. In an instant, I saw the guerrilla commander at my feet, gagged, and the rescue leader, yelling, “We’re the Colombian army! You are free!” And the shriek that came out of all of us when we regained our freedom continues to vibrate in me to this day.

Now I know they can divide all of us; they can manipulate us all with fear. The “No” vote on the peace referendum in Colombia; Brexit; the idea of a wall between Mexico and the United States; Islamic terrorism — they’re all examples of using fear politically to divide and recruit us. We all feel fear. But we can all avoid being recruited by using the resources we have — our principles, unity, faith. Yes, fear is part of the human condition as well as being necessary for survival. But above all, fear is the guide by which each of us builds our identity and our personality.

I was 41 years old the first time I felt fear, and feeling it was not my decision. But it was my decision what to do with it. You can survive by crawling along, filled with fear. But you can also rise above that fear, spread your wings, and soar. You can fly high — so high until you reach the stars, where all of us want to go.