The Good Country Index measures how much each of 125 countries contributes to the planet. Announced at the TEDSalon in Berlin, the Index features some unexpected winners — and even more surprising losers. (Sorry, USA.)

Irish people, rejoice! It turns out, your green land is the “goodest” country in the world. That’s right. The “goodest.” At least, that’s according to Simon Anholt, who’s spent the past two years compiling an index to determine which of 125 countries contributes the most to the common, global good. Watch his TED Talk, “Which country does the most good for the world?”

“I wanted to know why people admire Country A and not Country B,” Anholt said in a phone interview before he unveiled the full Index at the TEDSalon in Berlin on Monday, June 23. “To cut a long story short, I discovered the thing people most admired is the perception that a country is good. That turned out to be much more important than the perception they’re rich or beautiful or powerful or modern or anything like that. So then I wanted to know which countries are perceived to contribute the most to humanity — and which countries actually are good.”

Good news, then, for Ireland. Less good news for the likes of the United States, which didn’t even make the top 20, coming in at number 21. “If the ranking were based on the total contribution of each entire country rather than per dollar of GDP, it’s likely the U.S. would have ranked a bit higher, as its total contribution is so great,” acknowledges Anholt. “But then again, so is its total debit and harm.”

We caught up with Anholt to find out a little more about the process of compiling the Index, to see why he thinks citizens treat politicians like prostitutes, and to gauge what kind of response he’s seeking now. An edited version of our conversation follows.

How does the Index work?

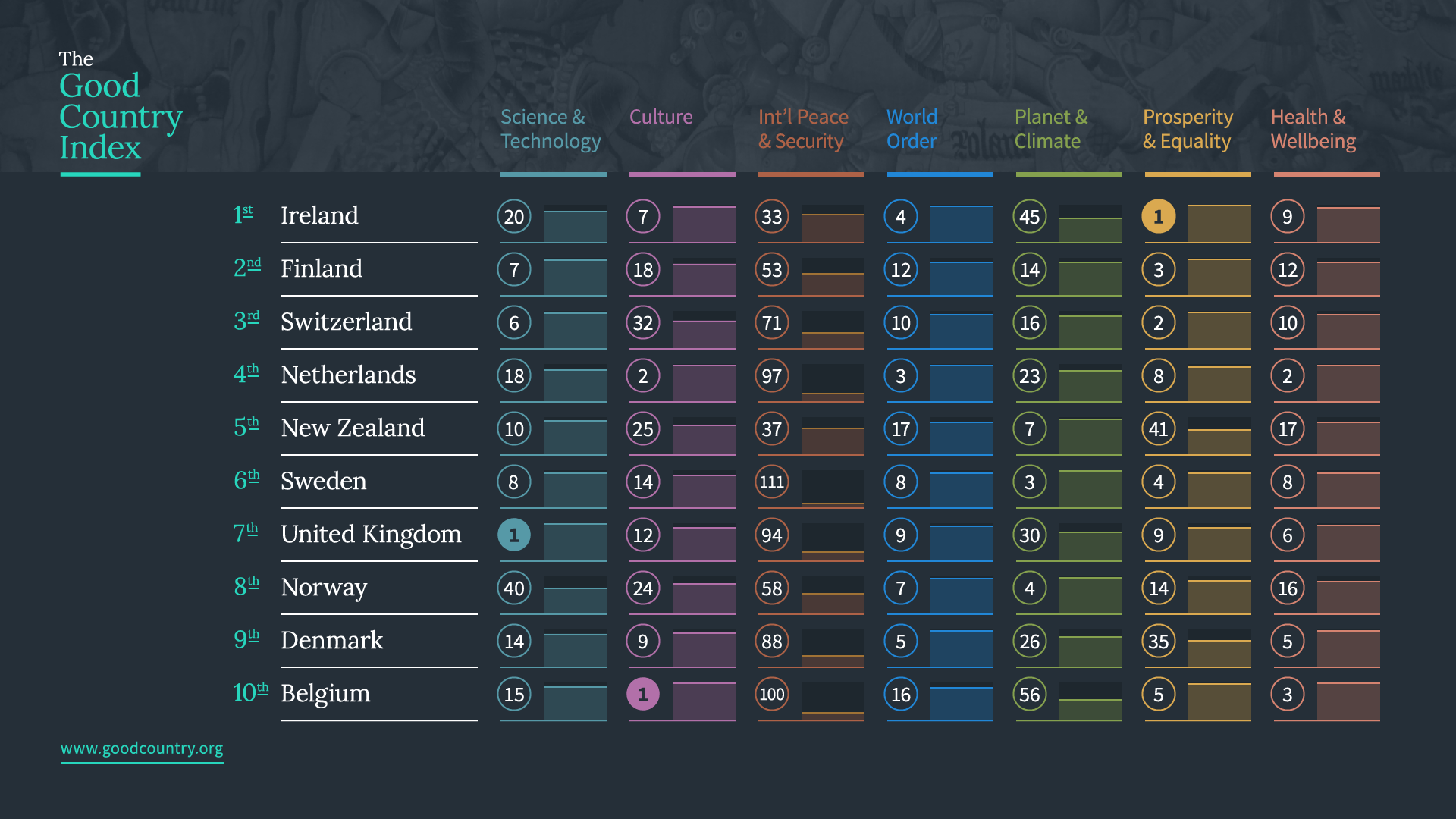

There are 125 country balance sheets graded across seven categories, including things like science and technology, world order, prosperity and equality and health and wellbeing. Each of those seven has got five datasets in them. Take for example world order. That includes five data sets representing things like how much each country gives in charity and overseas development, its population growth, and its status of ratification and signatories of UN treaties.

“Countries perform better and better but the world and planet and humanity in general are getting worse and worse.”

How did you determine which data sets to use?

There’s a PR answer to that and there’s a real answer. The real answer is there’s not a lot of choice; there simply isn’t all that much good data on every country on earth available. To collect reliable data on one country on something like its number of migrants is a gigantic task requiring hundreds of people and thousands of hours to collect. Trying to do that for 200 odd countries is really an enormous piece of work. The 35 sets I’ve used are probably half of the good robust data sets that are actually available in the world. Luckily, the data sets work quite well.

There’s a lot of talk of “big data” at the moment, but what you’re pointing out is a simple but fundamental point that’s often overlooked: You have to rely on what’s available to you. I know from my own research that sometimes I’ll try to find stats and the most recent report will be from 2009, say. So even if it’s great data, it might be hugely out of date. How do you get around this — and how recent is the data in this Index?

Trying to figure this out took an enormous amount of time. No one has ever brought such a diverse breadth of data together. And the first thing you notice is that their timescales are totally different. Some of this stuff takes literally decades to collect. And some of it is very slow-moving stuff. For instance, it can easily take 15 years between a UN international treaty being tabled and being ratified.

So we ended up with the slightly disappointing year of 2010. Disappointing to anyone who doesn’t know how this kind of stuff works. The reality of the matter is 2010 is the epicenter of a cluster of where most of the recent data lies. That’s fine, this is the first Index, so in a sense it’s a baseline; this is our portrait of the world in this decade. And an awful lot of data doesn’t change year on year anyway.

So despite the disparity in the measurements, the different timeframes, the different everything throughout the data, you stand behind this Index. Couldn’t someone reasonably pick holes in the approach?

The objections to the approach massively outnumber the supporting factors. I have become the world’s leading expert on why this is a crap idea. And I decided to do it anyway. The simple reason that I’m not claiming to have the final answer on any of this. This is a very well constructed piece of research, but it’s by no means the final answer, because you couldn’t have the final answer unless you had enormously more data than is currently available. So it’s designed to be basically a step in the right direction.

“Countries still behave as if they weren’t connected; they still measure their performance entirely inwards.”

What do you want people to take away from the Index?

The reason I’ve done it is not because I wanted to do an index but because I wanted ordinary people — not politicians — to start thinking about whether countries are good or bad. At the moment all they ever talk about or measure is whether a country is successful. We have fallen into the habit of measuring the performance of countries as if they were islands, as if they had no connection with each other, and as if one country doing well had no impact whatsoever on other countries. But of course this is the age of globalization, and the central fact of the age we live in is that every country, every market, every medium of communication, every natural resource is connected. A chicken catches a cold and sneezes in a Chinese village. 20 years ago that would only have been bad news for the chicken and its immediate family; today it threatens the survival of the human species because of globalization. Two small banks fail in rural America. 20 years ago that was no problem except for them and their communities; today it knocks the entire global economic system for six.

And you don’t think that countries are legislating effectively for the global age?

Countries still behave as if they weren’t connected; they still measure their performance entirely inwards. My argument is that we can’t just blame governments for this, it’s the fault of populations who don’t demand anything different of them. They say they want three percent growth or they’ll vote for someone else. We have to start asking where that growth comes from. We are screwing poorer countries to buy products more cheaply, we are raping the environment to produce more energy to drive our industry faster. Countries perform better and better but the world and planet and humanity in general are getting worse and worse. The whole system starts to look like a rapidly growing tumor. It has an illusion of health because of its growth but it’s almost as big as the host body.

How will thinking globally help?

It’s essential to get ordinary people along with politicians and businesses and so on to start to ask themselves about the international implications of what they’re doing. That’s what I mean by a “good” country. I don’t mean morally or ethically good, but a country that considers the common good as much as it considers its own citizens. By day I’m a policy advisor, I advise presidents and prime ministers around the world, 53 of them in the last 20 years, I haven’t seen a single example of a domestic issue or policy that wasn’t massively improved by considering the international context.

But wouldn’t you agree that there’s a pretty big disconnect between policy makers and “ordinary” people? How do you make people aware that they have to pay attention — and appreciate that they actually can influence said policy makers?

There used to be this automatic and universal relationship of love and trust between citizens and their cities or their city states, the equivalent of the modern country. What that is being replaced with today is a relationship of prostitution. It’s very simple: We throw money at the government as if they were hired management teams and tell them to sort out our problems and they’ll hear from us if we don’t like the way they do it. It seems to me that’s a very sad thing and it has to somehow change.

It’s interesting to hear you describe the government as basically crap middle managers to whom we have delegated the task of running the world. Business plays such a big part in this — particularly with globalization. Certain companies are arguably more powerful than countries now. How does that play into the Index? And what of the fact a public company has a fiduciary duty to do the best it can for its shareholders, which might contradict what we otherwise see as being “good”?

Just as public companies have a fiduciary duty to shareholders, so there’s an unwritten supposition but very real rule that a government’s primary duty is to its citizens. No one would dream of questioning that. And I don’t, either. I just say it’s not impossible to align that with a broader, further-reaching, longer agenda.

The fact is that companies are way ahead of countries in this. They underwent a revolution ten, twenty years ago of Corporate Social Responsibility. In fact, when I first started working on this, I came up with this ludicrous tag, “Governmental Social Responsibility,” because it’s an exact equivalent. Now, people love to sneer at CSR, and when you probe to find out why, the main answer seems to be that people think that companies are being hypocritical. And that’s interesting because I don’t think it matters. I’ve seen this work over and over again. Someone starts behaving in a right-on way for purely cynical reasons, they’re lying through their teeth, just doing it for PR. But the moment it starts working — and it usually does work — and they start receiving some of that warmth from public opinion, it becomes the most important thing they’ve ever done. Their reputation, as soon as they start to earn one, instantly becomes their most treasured possession. They will do anything to maintain that reputation and build it further; they will even become good — even that! — in order to maintain it. That little loophole in human nature is probably what will save us all.