Aziz Abu Sarah explains how he recovered from the murder of his brother and learned how peace and love can be potent tools of activism.

“You are responsible for the terror attacks” said a man after a lecture I gave about religion and violence at an interfaith event in New Jersey two years ago. “Your people are trying to kill us.”

He was frustrated and furious. I get these accusations often, particularly after attacks like the one in San Bernardino, California, last December. But I know his feelings very well. Pain doesn’t differentiate between ethnicity, color or religion. I am a Palestinian who grew up in Jerusalem, but I now live in America — so any attack here is an attack on my home, too. Over decades, many friends and colleagues in the Middle East and Afghanistan have been killed or displaced by terrorist attacks and ideology. So I, too, have felt fury — and my own anger and hatred fueled eight years of destructive activism.

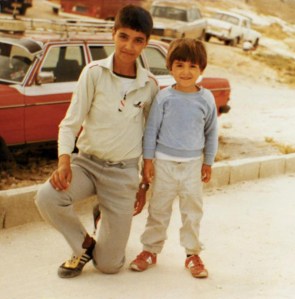

My brother Tayseer was killed when I was 10 years old. He was only 19, and his Israeli interrogators had beaten him in prison so that he would admit he’d thrown rocks at cars. He died from internal injuries soon after. His death enraged me, left me buried in feelings of loss, emptiness and unanswered questions, and I spent the remainder of my childhood feeling that I had no choice but to avenge his murder and fight back. For the rest of my youth, the idea of revenge consumed and drove me.

Meanwhile, to grow up in Jerusalem as a Palestinian meant living in constant insecurity. We had to move from our house because Israel legally declared we were outside the borders of the municipality of Jerusalem. I was told I couldn’t go to my school any more because it was in the wrong catchment area. For months I had to sneak my way there, running around checkpoints, getting shot at, being beaten if I got caught. I carried an onion to counteract the tear gas. Every day was a fight.

I knew now I couldn’t let those who murdered Tayseer drown me in blind hatred and anger.

By the time I was 13, I was very active politically. I read a lot, I participated in protests that sometimes turned violent, I threw stones. By the time I was 16, I was already a leader of the youth movement for Fatah, one of the biggest Palestinian secular political groups. I became an editor of Fatah’s youth magazine in Jerusalem, and I mobilized huge protests. Three of my fellow students were killed in these protests. It was a destructive time, and the future looked to hold more of the same.

Then, miraculously, I had a change of heart. It began with my first encounter with Israelis and Jews in a Hebrew class when I was 18 years old. Hebrew was mandatory at my high school, but I had flatly refused to learn it. It was the language of the enemy — no way. But now I needed to learn it or else forfeit the chance of a higher education. So I enrolled in a class designed for Jewish immigrants to Israel — and for the first time in my life found myself face-to-face with Jews who weren’t soldiers or settlers. Talking with them, discovering their mundane normality, our mutual love of coffee, country music, food, slowly, very slowly, brought down my walls.

Funny as it might sound, it was painful to make these new friends. Coming to terms with my own demonization of Jews was harrowing. I was stunned at how it had allowed me to disregard people’s common humanity. We weren’t so different after all. I knew now I couldn’t let those who murdered Tayseer drown me in blind hatred and anger. I could choose whether to respond with hatred and violence, or with grace and love.

Tentatively, I began choosing to respond with love. I found that it changed things. It might not change others’ minds, but it did change me: it taught me forgiveness. I remember waking up every morning and saying to myself, “I forgive, not because the person who killed my brother deserves it, but because I want to forgive.” It was so redeeming, so transformational. Suddenly, the next time a bomb went off in West Jerusalem, I didn’t think, “Oh they’re my enemy, who cares?” I thought, “Wait, my friends live there.” I started calling to make sure they were safe.

My journey to forgiveness began by being willing to take a first step out of my comfort zone. I forced myself to stay with this discomfort. I learned about Judaism as a college student by working in an ultra-Orthodox neighborhood, then I attended an evangelical Bible college to learn more about Christianity. Later in life, I’d spend day after day filming with the Israeli army for a National Geographic web series on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These sometimes painful experiences forced me to challenge my assumptions about the “enemy.” They didn’t always change my opinions and convictions, but they gave me a much better understanding of — and compassion for — others.

Terror is claiming many lives, but we must not let it claim our souls as well.

Since then, I’ve made it my life’s work to bring down walls between people by promoting education, advocacy — and interfaith, intercultural tourism, because travel is a vital educational tool, countering xenophobia and cultural superiority. I search for ways to expand horizons and connect people with each other — not just Arabs and Jews in Israel, Palestine, Jordan and Turkey, but Catholics and Protestants in Ireland, Bosnians and Serbs, and so on. I believe this is essential for building a peaceful future.

Terror is claiming many lives, but we must not let it claim our souls as well. We cannot afford to let continuous news of escalating violence turn us back in fear to old narratives of blame, thinking they will keep us safe. Let’s use this opportunity to tolerate the discomfort, however small, to try and understand where other people may be coming from. It’s not as expedient as a military strike. But in the long term, it’s the only moral way to break the cycle of violence.

I can’t forget my brother. I don’t think what happened to him is OK. But forgiveness is not about condoning violence or renouncing justice. It’s setting yourself free from anger so that it doesn’t consume you. That energy can then be used to bring people together. Now, whenever I read the paper and see more people being killed, the energy of my rage is transmuted into the question: “What can I do to stop this?” That kind of anger, I think, is okay.