You can gain strengths and abilities you didn’t know you had from fantasy role-playing games, says writer Ethan Gilsdorf.

You’re a member of a team of adventurers, and your shared quest is to rescue a prince who has disappeared near an abandoned castle. In this mission, who do you want to be? A brave dwarf warrior? A brainy human wizard? A skilled elvish archer? A stealthy hobbit thief?

As you approach the ruins, you see a creature. It’s nine feet tall, green and grumbling, and it carries a massive axe. A troll, it’s chained to the entrance gate. What do you do? Rush and attack? Blast it with a magic fireball? Sneak around and find another way in? Try to bargain with it? Or something else?

I grew up in an isolated New Hampshire town before the Internet, smartphones and social media. Like most kids, I played board games like Risk, Stratego, Mousetrap, Battleship, Clue, Monopoly.

Then, in 1974, came Dungeons & Dragons, or D&D — a game that changed everything. D&D introduced rules for fantasy role-playing in a swords-and-sorcery world. I first encountered D&D in 1979 when I was 12, and it blew my mind. My buddies and I played it a lot.

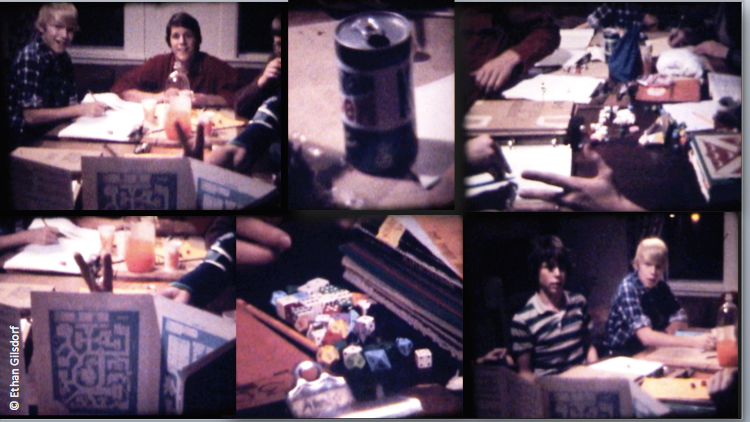

These stills are from a home movie I shot in 1981 and should give you an idea of how the game is played. There are maps, rulebooks with names like Monster Manual and Dungeon Master’s Guide, and lots of strange polyhedral dice. You’ll also notice Mountain Dew and Doritos — key provisions for a quest.

And, as you can see, there’s no board. D&D is played in your imagination. Each person is a character that has certain powers and weaknesses, represented by statistics that you keep track of on a sheet of paper. For example, you might have a strength of 16 (out of 18), which is good, or a charisma of 3 (out of 18), which is not so good. Each character also has a level — if you’re level 2, you’re still wet behind the ears — and a name, personality and special abilities. One player, the Dungeon Master, or DM, dreams up the adventures that the players will go on and creates the world, the backstory of its peoples, creatures, magical lore and legends. The DM also serves as the game’s referee and god.

As a player, you “play” by describing what your character wants to do. “I ask the bartender when she last saw the prince,” you might announce, or “I strike the troll with my axe.” The roll of various dice and the DM’s judgment determine the success or failure of any action. It’s sort of like reading The Lord of the Rings — but as you read, you get to decide the paths of each character. Best of all, no one knows what happens next. Games can last for weeks, even years.

When I first started to play D&D, I was dealing with a lot of my own monsters. The same school year that I discovered role-playing games, my mother suffered a crippling brain aneurysm that left her physically and mentally disabled. She was unpredictable and behaved strangely. She scared me. I was already a hopeless introvert, and her illness made me feel even more powerless, even more trapped in the maze of adolescence. The game allowed me to escape my fears and navigate a fantasy world as someone else — someone with power and agency.

I played D&D obsessively, every Friday night from eighth through twelfth grade. Then, I stopped for 25 years. When I returned to D&D in my forties, I realized something. Role-playing games had shaped me. They provided a powerful coping mechanism. They had given me powerful tools. They saved me.

But I believe fantasy role-playing games have the ability to benefit anyone. Here are five ways in which D&D and the power of fantasy can help you combat the perils and challenges of reality — and make you a better person in real life.

1. You’ll get to be part of a team.

Unlike in Monopoly, in fantasy games you’re not a ruthless real-estate mogul bankrupting your fellow players by putting hotels all across Middle-earth, from Hobbiton to Mordor. While you can complete some tasks on your own and make individual decisions, most of the story action requires your adventuring party to work together to accomplish quests.

Collaboration means recognizing the power of teamwork and diversity. In D&D, humans can’t go it alone, and neither can any other culture — be they elves, dwarves, wizards, thieves or warriors. Let’s go back to that scenario with the troll. Let’s say your characters choose to fight the monster. Your team has a range of skills to draw from — spell casting, fighting prowess, healing powers, seductive charm. Each member plays a part.

The same occurs in the real world with your officemates, your family or other groups when you have to finish a project at work, host an elaborate meal, build a startup, or plan a trip. Each person in the circle contributes. D&D’s lessons are: Celebrate your differences; it’s OK to rely on each other; I’ve got your back.

That surging feeling of camaraderie — of being part of something bigger than yourself — is a powerful thing. As a kid, I was too uncoordinated to play team sports, but I received the bonding experience of mutual accomplishment through D&D. (Who needs football when you can shoot fireballs from your fingertips?)

2. You’ll learn how to solve your way out of anything.

Beyond providing the thrill of victory, these role-playing games also help you solve problems. Let’s say you attack the troll and kill it. You ransack its body and find a scrap of paper with a strange message scribbled on it: L L C R C L. What could that mean? You don’t know, but you hang onto that scrap. Maybe it’ll come in handy later.

Your party enters the dungeon under the castle. It’s dark and scary. Luckily, you’ve brought torches, rope, grappling hooks and a wand that shoots giant spider repellant. Life is like that dangerous dungeon — you need to be prepared, and you shouldn’t wander through it without the tools to MacGyver yourself out of trouble. For instance, you wouldn’t drive a car without having a spare tire in the trunk. Or when you walk your dog, you know to bring your smartphone, some treats, and extra poop bags.

Back to the dungeon. You discover a long corridor with a strange pattern of tiles on the floor. Your loveable but blundering dwarf steps on the first tile. You hear a click. Arrows shoot out at you from the darkness — it’s a trap! Then, you remember that scrap of paper. Could it be a code? Maybe L means left, C is center, R is right? You step on the tiles in that order, and voilà, you pass through unscathed.

But there’s more than one solution to this puzzle — and most puzzles — both in D&D and in life. You could disarm the trap; set off the arrows by rolling a large rock down the corridor; bribe a lowly orc to walk in front of you to trigger the trap. The point is, role-playing games teach innovation. They train the mind to solve problems, make unexpected connections, and discover alternative paths through the darkness.

3. You’ll grow in character.

Solving problems also requires perseverance. You must begin at the first — the lowest — level. You’re a wuss with just four hit points. You have a rusty sword. You cast a spell that makes … pancakes. Have patience. As you gain experience points, you will grow in skill and strength. You do this by taking risks, which lead to reward.

Let’s go back to the troll. Want to leap from the castle wall onto it, and bang the monster on the head with a rock? Go for it. The game lets you take risks and fail in a safe environment. Sure, your character could be gravely injured or even die (if your DM is particularly mean). But that’s a chance you can take in the game, and the risk is made all the safer because your fellow teammates are there to catch you if you fall. If you die, a cleric can resurrect you. And you get to try again.

Take it from this 17th-level nerd, it gets better — you can and will heal from defeat, setback, embarrassment. If I’m shy and fearful and stupid in real life, in the game I can play a wise and fearless dwarf. I can practice being courageous or wise in these fantasy worlds before I’m ready to be courageous and wise in real life. Playing D&D empowered me to confront my arch nemesis at school and my mother at home, so I could live and fight another day.

4. You’ll gain empathy for others.

Another step in building character is developing empathy and tolerance. You and me, we’re separate beings — I’m the “self”; you’re the “other.” So, how do we bridge that gap? Role-playing creates that intersection.

In fantasy gaming, you inhabit someone else’s skin. You can choose to be someone like you, or someone not at all like you. The game’s immersive narrative forces you to interact with others (elves, trolls, dragons, bartenders) all the time. In a fantasy world, you don’t wander around assuming people — and creatures — look, act and think like you. And you can’t help but imagine their predicaments and experiences. The DM might say, “The dragon tells you she’s certain the townspeople have painted her in a bad light.” Or: “You enter the forest glade and see a small band of goblins dressed like the group that nearly killed you in the dungeon under the castle. But these goblins are children. What do you do?” D&D poses important ethical thought experiments to test human, elvish or orcish behavior and help us model how we might behave in the real world. That, my friends, is why D&D is the perfect engine for empathy training.

Because of the game, I can look at everyone — the annoying driver on I-95, the bossy colleague at work, my sick and broken mother — with just a tad more empathy, compassion and love.

5. You’ll tap into one of the greatest talents of all: your imagination.

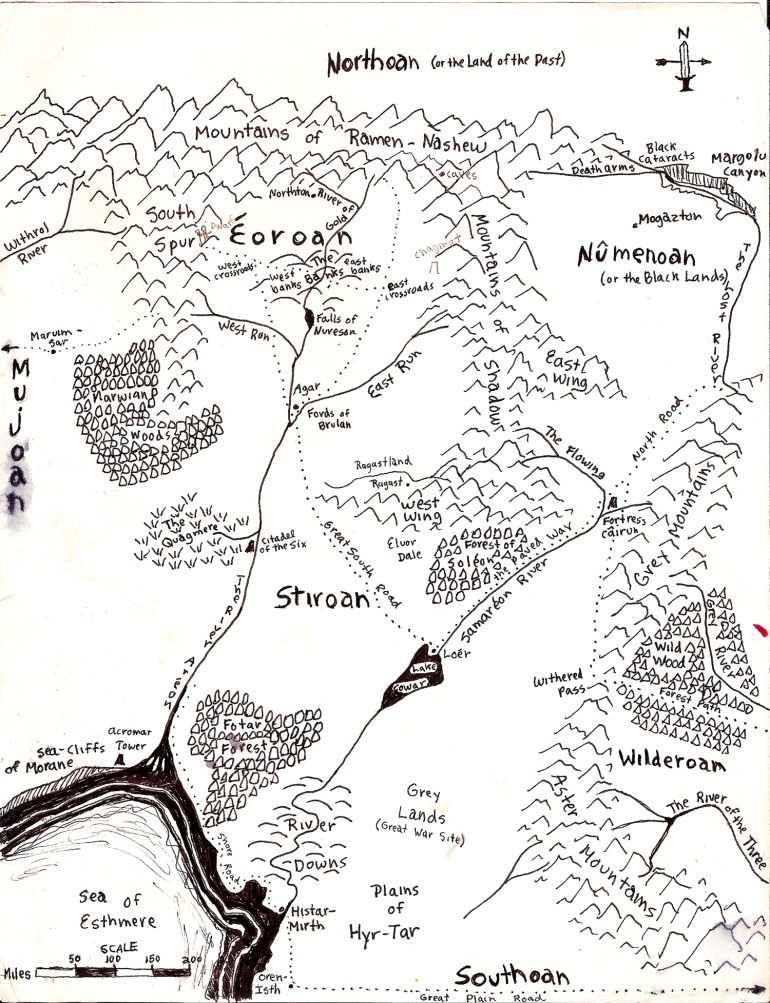

These games don’t work without story and imagination. Look at this map I drew back in the Reagan Administration:

Focus on it for a moment. I’m guessing your wondering mind is now activated. You’re asking questions like, What is this place? Who lives here? What’s the story? What happens next?

While movies, TV shows and video games offer immersive narratives and worlds, they don’t engage the imagination in the same way that D&D does. The game’s crude tools — its maps, sketches, dice, books, figurines — force you to fill in the gaps. You must bring your imagination to the table to complete the picture.

Humans used to sit around the fire telling each other stories. But today, most of us settle for being passive consumers of Hollywood narratives made with millions of dollars and thousands of digital animators. Storytelling, it seems, has been taken from us.

Fantasy role-playing games return that power of storytelling to us. D&D sparked my imagination and kindled an interest in everything from geography to languages, history to poetry. It made me want to create, to be a storyteller and a world builder. And to take a leap and imagine a better world.

Which leads me to this game’s most powerful magic. Stories not only connect us; they create hope. In D&D, there’s a rule. If you’re trying to do something and you roll a 20, no matter how impossible the odds, it happens. You can slay the troll with a single shot, kiss the girl, love your mother.

Deep inside each of us is a dungeon with a powerful dragon. You won’t know whether you can defeat it — or even befriend it — unless you try.

This piece was adapted from a talk that the writer gave at a TEDxPiscataquaRiver event.