Take the strategy employed by memory athletes to memorize decks of cards and thousands of digits of pi, and adapt it to get over stranger-name forgetfulness.

You’re at a social function — it could be a work-related meeting, a friend’s birthday, a community function — and you start talking to a stranger. The two of you chat for a while, but as the conversation winds down, the other person calls you by name and then says, “It was great to meet you.”

That’s when you realize you have no idea what their name is — and they told you just minutes ago.

How often has this happened to you? And what’s a person to do?

It seems you’ve got three main options: 1) mask the awkwardness by responding with an over-enthusiastic “So great!” or an overly toothy grin; 2) limit yourself to events where name tags are mandatory; or 3) shun society and embark on life as a recluse.

But might we suggest a fourth option? Try this advice from memory champs Kevin Horsley and Daniel Kilov.

Recognize that you probably don’t have a problem.

That’s right: You don’t. For most people, “there’s no such thing as a good or bad memory,” says Horsley, an International Grand Master of Memory based in South Africa. “There’s only a good or bad memory strategy.”

According to Horsley, your problem is most likely plain and simple distraction. Think back to the last time that someone’s name went in one ear and out the other. Were you in an unfamiliar space, and was there also unfamiliar music, furnishings or people? Were you in a situation where you really wanted or needed to make a good impression? And were you worried about who you would talk to or what you would talk about? With so much external stimuli and internal stress, it’s not surprising that your attention became fragmented.

Change your strategy.

Rote memorization — repeating things over and over until we retain them — is what many of us are taught to do in school, but it doesn’t work well for everyone. Growing up, Kilov found it “dull, impersonal and ineffective.” He admits, “I didn’t have a good memory in school.” Then, Kilov contacted memory champion Tansel Ali and after a few months of practice and coaching, he placed second in the Australian Memory Championships (just behind Ali). All he needed were different techniques, and today he can memorize a shuffled deck of cards in less than two minutes.

Make associations.

The primary approach used by memory champions like Horsley and Kilov is to make compelling associations that stick in the mind like a TV commercial jingle. They do this by linking the information they want to remember to people, characters or things they’re already familiar with.

Take the following as an example. First, picture the Sydney Opera House. Inside, author Toni Morrison is playing the bagpipes and wearing a Scottish kilt. Next, out in the harbor, Malcolm X is driving a speedboat and making his only passenger, a bull, seasick by turning the craft around in circles. Nearby, Tony the Tiger is walking across the Sydney Harbour Bridge, and he’s dressed in monk’s robes. Now close your eyes and make these images as vivid as possible in your mind.

Congratulations, you’ve just learned, in order, the names of the three most recent Australian Prime Ministers: Scott Morrison, Malcolm Turnbull and Tony Abbott. (Editor’s note: This may not be so exciting for Australian readers.) Please know that this strategy works best when you follow your own personal interests. Perhaps the best way for you to remember the name “Scott Morrison” is by picturing a Scottish terrier chasing the Doors’ Jim Morrison.

Make your connections as entertaining as possible.

The more vivid and the more personal your imagery, the likelier it is to stay in your mind. While creating mental pictures may seem like a childish exercise, no one will be able to see what’s going on in your brain (yet). And, as Horsley points out, there’s a good reason that children pick things up so quickly. Think about how kids first learn about a puddle. “What does that child do with that puddle?” he asks. “They jump in, they experience the moment, and they have a little fun.”

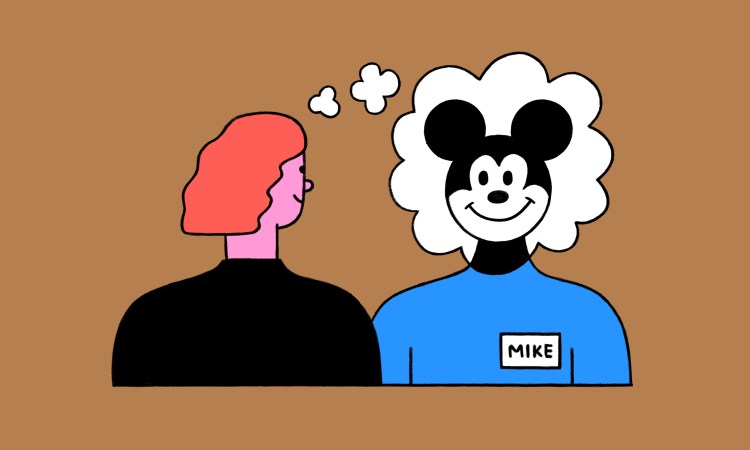

Incorporate the person’s face into your imagery.

When you use this technique with people you meet, make sure their face is part of your mental picture. The easiest way to do this is to place them at the very center of your tableau. This is important: Otherwise, you’ll recall their name but have no person to tie it to.

This approach can work for names with less obvious association, and that will also give you a chance to flex your creativity. Let’s say you meet someone named Hasiba Aziz. For her, you could envision a laughing zebra sitting next to snoring donkey (Ha + Zebra + Ass + Zzzzzs).

And just remember (ha!): There is no shame in asking someone to repeat their name.

If, at the end of the conversation, you find you can’t recall the other person’s name, say, “I’m so sorry, but I’m a little distracted by the music/chatter/crowd/etc. Can you tell me your name again?” Then, try to create your image association for them before you start talking to the next person.

Watch Kevin Horsley’s TEDxPretoria talk here:

Watch Daniel Kilov’s TEDxMacquarieUniversity talk here: