Between them, Dave Isay, TED Prize winner and founder of StoryCorps, and Brandon Stanton, founder of Humans of New York, have collected more than 75,000 stories from regular people around the world. Isay collects his stories as audio files, while Stanton takes a photo and then interviews his subject — but they’ve both developed fascinating techniques for helping people to open up. They sat down recently to talk about their work and their thoughts on what makes for an honest, open interview environment.

A supportive culture breeds good stories. “We think of the internet as such a coarse place, yet people treat our app with such respect. I am constantly amazed by this,” Isay says about the listener contributions to the StoryCorps app. The secret, he says: Create an intimate culture where trust is paramount. Stanton agrees. “We don’t judge or criticize,” he says. “I am interviewing people with a spirit of genuine interest and compassion, and therefore the general tone of the site is one of genuine interest and compassion.” Maintaining that spirit is the only reason he thinks Humans of New York survives. “The moment that culture changes, Humans of New York is no longer viable,” he says bluntly. “If I approach someone and ask for a photograph, and they know they’re going to be subjected to a judgefest, suddenly it’s not a great proposition anymore, it’s something to be feared. I can exist without the audience; I can’t exist without the people telling their story.”

Engage deeply. Interrupt kindly. People aren’t very good at knowing how to tell their own stories, says Stanton, and that means that they’re often vague and imprecise. Cutting through that is part of the interviewer’s job. “Interviewing someone is a very proactive process and requires taking a lot of agency into your own hands to get past people’s general normal self-preservation mode,” he says. “My interviews are very pointed. I’m an active participant; I will kindly interrupt people. But I’ve learned there is nothing people won’t tell you if you ask in a compassionate and legitimately interested way.” Isay agrees: “When I started making radio documentaries, I wanted to be the vehicle through which people could tell their stories.” But that doesn’t mean letting them ramble.

Trust in people. “StoryCorps has made me less fearful of other people,” says Isay. “I’ve learned really bad people are few and far between, even though that’s not represented in newspapers in the culture of fear we live in.” By giving people tools with which they can share their own stories, he’s become hopeful that people are basically good. “People want to have these conversations, but it can be hard and scary. I think about it like jumping in a freezing cold pool. You just have to do it and take that step and do that interview.”

Do not commodify your stories. “The only things I make money on are speeches and books,” says Stanton; HONY might have 15 million followers, but he doesn’t sell advertising. “I want HONY to be about telling the stories of people, and there’s part of me that does not like the idea of making money or selling advertisements based on the value of other people’s stories.” StoryCorps, meanwhile, has always been a nonprofit. As president, Isay spends most of his time fundraising — a task he is happy to do, he says, because it allows StoryCorps to be StoryCorps.

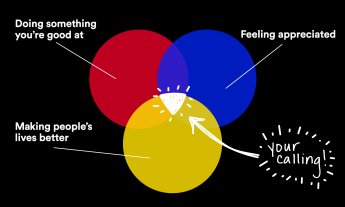

If you have a calling, pursue it relentlessly. “The first interview I ever did, I knew that was what I was going to do for the rest of my life,” says Isay. Not, he says, that it was always easy: “It takes some courage to find your calling and just do it no matter what anybody says.” For his part, Stanton had been working in finance when he lost his job. “All I knew was that I loved photography, so for the next few months I did nothing but photograph all day long,” he says. That was the beginning of HONY. “If I had waited until I was ‘ready’ to do HONY, it would have never gotten done.” As Isay confirms, “you just gotta jump.”