Computers have become so powerful that the idea they can’t just do, you know, everything is almost unfathomable. Yet many calculations are still too big for even the biggest supercomputer to process — like cracking complex encryptions or modeling global weather systems. That’s where the promise of quantum computing comes in. With the principles of quantum mechanics at its core (more on this below), quantum computers can, in theory, provide exponentially more power and speed than today’s supercomputers — in a much smaller space. The idea has been around for decades, but today, scientists like TED Fellow Jonathan Home and his team at the Institute for Quantum Electronics in Switzerland are, atom by atom, taking quantum computing out of the realm of theory and into reality. Here, Home walks us through how quantum computing works, some of the challenges of creating a fully functioning system — and how it could one day be used.

Quantum computing: where bits are atoms. So, what is the difference between regular and quantum computing? Quantum computing promises much more power in much smaller packages. Here’s how. In a regular computer, the physical system is a chip, and information is coded in bits, using the binary system — a bit is either a 1 or a 0. In a quantum computer, the physical system is an atom, aka a qubit — and quantum mechanics allows an atom to be a 1 and a 0 at the same time. (Don’t worry. This idea hurts everyone’s head, even quantum physicists’.) In other words, each atom can hold twice as much information as a regular bit. Another important difference: “In a normal computing system, you can try one number at a time, whereas a quantum computer can solve multiple problems in parallel,” says Home. This means that if quantum computing comes to fruition, we would, in theory, end up with a machine that’s both smaller and exponentially more powerful than our current machines.

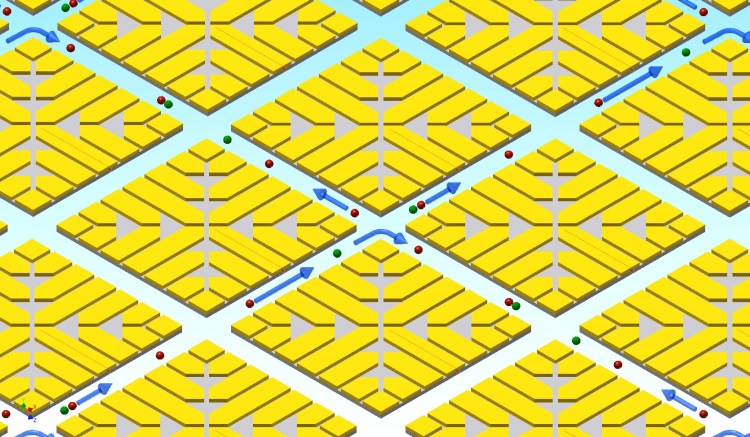

A quantum computer is built atom by atom. The current, painstaking challenge: getting more atoms to work together, forming stable circuits. “The task of building a quantum computer takes a long time, and is full of important progression rather than ‘breakthroughs,’” says Home. “But quantum computing is already real, in the sense that we are actually building small devices which can do simple algorithms according to quantum mechanics.” In 2009, Home and colleagues at the National Institute of Standards and Technology were able to put together the basic components of a quantum computer, with two quantum bits forming the electrical circuit that’s the basis of all computing. Now, he and his team at the Institute for Quantum Electronics are building on that work, figuring out how best to control more of the individual atoms needed for quantum computing. One method is freezing and manipulating multiple atoms — around 10 — with laser light and nudging them together to form circuits. Experiments like this are exciting, small, proofs of concept that show quantum computing is possible.

But, says Home, a fully functional quantum machine requires around a million atoms, and it’s very difficult to predict when they’ll be able to work with such numbers. “The work we’re doing may turn out to allow quantum computers to be scaled up from small demonstrations into full-scale computational devices,” says Home. “Another possibility is that we might discover new physics as we are able to build larger systems, but we don’t yet know what this would look like.”

Once we have them, quantum computers’ speed and size would let us tackle currently impossible problems. Right now, when scientists need to crunch a massive amount of data — say, sequence genomes or track weather patterns — they need big computers. Really big. The Cielo supercomputer, for example, housed at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, occupies 3,000 square feet. (Its predecessor, the IBM Roadrunner, was twice that size.) And for some problems, the scale of the computation you have to do grows exponentially with the size of the numbers involved. “If a problem is just one digit longer than your current supercomputer can handle, you’d need one that’s twice the size,” says Home. “That just becomes uncontrollable.” The time it takes to solve the problem similarly increases. A quantum computer could sidestep these issues. “Because of its design, a quantum computer could solve a problem it would take a supercomputer the age of the universe to solve in a week, maybe even a day.”

A very probable use for quantum computers, if and when we get them: breaking complex encryption. Many modern computer security systems are based on the assumption that computers can’t make extremely large, complicated calculations within a reasonable amount of time. For example, RSA cryptography — the encryption system commonly used for securing sensitive data like financial transactions — depends on the difficulty of finding the product of two very large prime numbers. Scientists estimate that factoring the large prime numbers we use for encryption today would take current supercomputers about 2,000 years, for example. But a quantum computer could expect to complete a similar task in a few days. This would change the game — and possibly endanger the world’s most sensitive information. “The US National Security Administration funds research into quantum computing, probably because they want to know whether it’s possible to build such a thing. If it is, others could use it against US infrastructure, and then they’re in trouble,” says Home. Conversely, it could also be used to create cryptography that’s harder to break.

Other applications for quantum computers include problems we haven’t yet thought up. “Quantum computing could allow scientists to calculate molecular structure, which means they would then be able to control and design molecules, or compute more efficient industrial reaction chains,” says Home. “But in all likelihood, we’ll use quantum computers for applications we never dreamed of.” After all, we created classical computers to calculate bomb trajectories and break cryptography — not to do word processing or post on Facebook. “It’s sometimes dangerous to limit yourself by saying, ‘I know what the applications of this are,’” he says.

Quantum computers won’t replace traditional computers. They are more likely to run in the background of our lives rather than replace our laptops and phones, because, for everyday applications, there’s no appreciable benefit to using the quantum machine. “If you do need to use a quantum computer to do serious calculations, they’ll be done remotely via the Internet anyway,” Home says.

The biggest challenge ahead: translating the laws of physics. “One obstacle is that as more atoms are applied to the quantum computing system, the margin of error gets smaller. Nevertheless there’s a beautiful theory that says you can correct all errors as long as your accuracy per operation is so good, 99.99% or so, and we’re not there yet,” says Home. The other obstacle is that integrating all the technologies that manipulate those atoms onto chips is technically very difficult. But Home says he thinks the proof of principle is all in place: “Nothing in physics seems to prevent us from getting to the goal — eventually.”