Behavioral economist Dan Ariely points out the surprising joy and engagement we feel when we make things.

We are the CEOs of our own lives. We work hard to spur ourselves to get up and go to work and do what we must do day after day. We also try to encourage people to work for and with us. We do this in our personal lives, too: from a very young age, kids try to persuade their parents to do things for them. As adults, we try to encourage our significant others to do things for us; we attempt to get our kids to clean up their rooms; and we try to induce our neighbors to trim their hedges or help out with a block party.

Rather than seeing motivation as a simple, rat-seeking-reward equation, I’ve found that it’s this beautiful, deeply human, and psychologically complex world. Motivation is a forest full of twisting trees, unexplored rivers, threatening insects, weird plants and colorful birds. This forest has many elements that we think matter a lot, but in fact don’t. Even more, it’s full of details that we either ignore completely or don’t think matter, but that turn out to be important.

By understanding motivation, we can structure both our workplaces and our personal lives in ways to make us more productive, more fulfilled, and happier. But how can we increase motivation? To answer this question, let’s think about building something — specifically, a piece of IKEA furniture.

The IKEA effect: we love whatever we build

IKEA came up with a brilliantly diabolical idea: the company would offer boxes of furniture parts and make customers assemble the items by themselves, with only the help of their bitterly impossible-to-understand instructions. I like the clean, simple design of IKEA furniture, but long ago, I found that assembling a piece — in my case, a chest of drawers for my kids’ toys—demanded a surprising amount of time and effort. I still remember how confused I was. Some parts seemed to be missing; I put some things together the wrong way more than once.

I can’t say that I enjoyed the process. But when I finally finished building, I experienced a somewhat odd and unexpected sense of satisfaction. Over the years, I’ve noticed that I look at that chest more often, and more fondly, than any other piece of furniture in my house. My colleagues — Michael Norton, a professor at Harvard Business School, and Daniel Mochon, a professor at Tulane University — and I have described the general over-fondness we have for stuff we’ve made ourselves as the IKEA effect. Of course, IKEA was hardly the first to understand the value of self-assembly.

Consider cake mixes. Back in the 1940s, when most women worked at home, a company called P. Duff and Sons introduced boxed cake mixes. Housewives had only to add water, stir up the batter in a bowl, pour it into a cake pan, bake it for half an hour, and voilà! They had a tasty dessert. But surprisingly, these mixes didn’t sell well. The reason had nothing to do with the taste. It had to do with the complexity of the process — but not in the way we usually think about complexity.

Duff discovered that the housewives felt these cakes did not feel like the housewives’ own creations; there was simply too little effort involved to confer a sense of creation and meaningful ownership. So the company took the eggs and milk powder out of the mix. This time, when the housewives added fresh eggs, oil, and real milk, they felt like they’d participated in the making and were much happier with the end product.

Effort adds to our affection and attachment

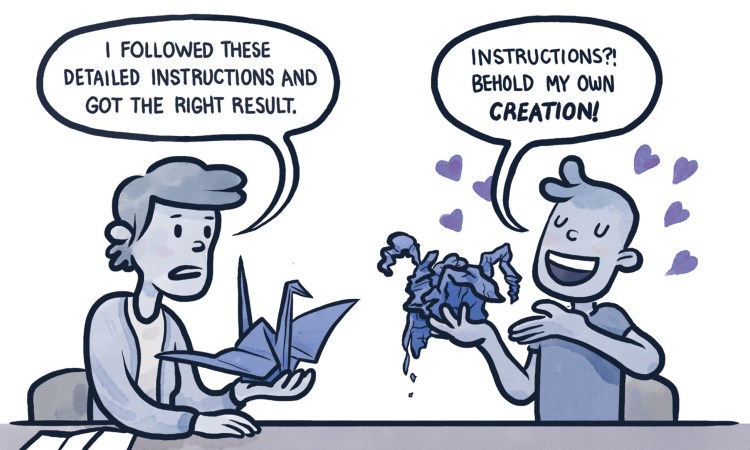

To examine the IKEA effect in a more controlled, experimental way, Daniel, Michael and I asked participants to make origami creations in exchange for an hourly wage. We equipped them with colored paper and standard written instructions that showed where and how to crease the paper in order to create paper cranes and frogs.

Now, folding a piece of paper into an elegant creation is harder than it looks. And since these participants were all novices, none of their creations was a terribly satisfying work of art. When their temporary employment ended, we told them, “Look, this origami crane you just made really belongs to us because we paid you for your time. But we’ll tell you what — we might be persuaded to sell it to you. Please write down the maximum amount of money that you would be willing to pay to take your origami creation home with you.”

We called these people “builders,” and we contrasted their enthusiasm for their creatures as measured by their willingness to pay for them with that of a more objective group we called “buyers.” Buyers were people who had not made anything; they evaluated the builders’ creations and indicated how much they would be willing to pay for them. It turned out that the builders were willing to pay five times more for their handmade creations than the buyers were.

Imagine that you are one of these origami builders. Do you recognize that other people don’t see your lovely creation in the same way that you do? Or do you mistakenly think that everyone shares your appreciation?

Before answering this question, consider toddlers. Little kids have an egocentric perspective; they believe that when they close their eyes and can’t see other people, other people can’t see them. As children grow older, they outgrow that kind of bias. But do we ever get rid of it completely? We don’t! Love for one’s handiwork is indeed blind. Our builders not only overvalued their own creations, they also believed other people would love their origami art as much as they did.

But wait, there’s more. In the impossible version of this experiment, we made the origami-folding task more complex by eliminating some of the most crucial details of the instructions. Standard instructions for origami include arrows and arcs that tell the user what and where to fold, as well as a legend that tells the user how to interpret these arrows and arcs. In this impossible version, we eliminated the legend — and our participants’ creations were even uglier. As a consequence, buyers were willing to pay less for the origami, but the builders valued their creations even more than when they had been given clear instructions because they put extra effort into making them. Just as my working hard on the IKEA chest of drawers increased my affection for it, our origami experiments showed that the more effort people expend, the more they seem to care about their creations.

Even choosing the color of your sneakers makes you a creator

It is important to note that our experiments with origami weren’t connected in any way to one of the main drivers of motivation — our larger sense of identity. Yet our participants’ behavior clearly revealed that we are strongly motivated by the need for recognition, a sense of accomplishment, and feeling of creation. The finding that these needs played such large roles in our lab experiments suggests to me that the same thing happens in real-world work environments, but in spades.

It’s easy to see how creators can garner a strong connection and a sense of identity and meaning from their accomplishments. It’s also easy to see how this research applies to artists, craftspeople and hobbyists. But what about the stuff we personalize as consumers? If you buy a pair of shoes online from Nike, for example, you can customize the colors of the shoes, laces and linings. Initially, this desire to customize seems to be about preferences — we choose red over purple because we like red more. But the reality is that customization has additional benefits. By choosing red, we make the product a little more our own. The more effort we put into the design, the more likely we are to enjoy the end product.

The same basic lessons of meaningful engagement also apply to many other aspects of our lives. If we have the money, we hire people to clean our houses, take care of our yards, or set up our wi-fi systems to avoid being bothered by these common chores. But think about the long-term joy we miss out on when we don’t engage in such tasks. Could it be that we end up accomplishing more but at the cost of becoming more alienated from our work, the food we eat, our gardens, our homes, and even our social lives? The lesson here is that a little sweat equity pays us back in meaning — and that is a high return.

Excerpted with permission from the new book Payoff: The Hidden Logic That Shapes Our Motivations (TED Books/Simon & Schuster, 2016), by Dan Ariely