Five years ago, a tsunami and nuclear disaster led to the mass evacuation of the Fukushima region of Japan. Photojournalist Michael Forster Rothbart covered the aftermath; last September he returned for a month to see how the situation has progressed. Here, he shares some of his portraits and reflections about the trip.

Hidekatsu Ouchi, farmer, current evacuee

Hidekatsu Ouchi is a farmer from Yamakiya village, right in the middle of the Fukushima Exclusion Zone. Although the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is more than 30 miles away, the worst contamination blew directly towards his village. He knows he’ll never be able to farm here again, due to the high radiation levels, but he hasn’t given up hope that he’ll be allowed to live here again. For now, he’s rented his farmhouse out to a team of radiobiologists for use as a research station — which gives him a reason to come back for regular visits.

During this trip, I asked some of the people I met to write down their hopes and fears for their towns. Standing beside his family’s shrine, Hidekatsu wrote his hope: “Somehow I want to restore Yamakiya to its previous situation by any means possible, and live there together (with all the original residents), all of us again.” His fear? That this is impossible: “Yamakiya, which I love and where I was born and lived until today, I worry how it’s going to be here from now on.”

Ikuro Anzai, nuclear scientist

Nuclear scientist Ikuro Anzai and his team measure radiation levels near Torikawa Nursery School in Fukushima City, and then report their findings to school director Miyoko Sato. The school’s staff had mostly kept children inside since the tsunami, concerned about radiation on the roads and at the nearby playground. Anzai and his team determined that the kids could go outside to play. “The disaster destroyed people’s trust in the government, in the industry, and in the experts,” he told my colleague Steve Featherstone for a piece we worked on for Popular Science. “I would like to apologize to the people in Fukushima. That’s why I go there every month to measure the radiation. I’ll continue to do this until I die.”

Yukiko Endo, waitress, evacuee

I was in Japan to cover the reopening of Naraha town, 12 miles south of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. It was the first town in the Fukushima Exclusion Zone to reopen after the disaster, and so far, only 440 residents have returned home, from a pre-disaster population of 7,400. Though she hasn’t moved back permanently yet, Yukiko is now working as a waitress in Naraha, and she wrote simply, “I hope Naraha has lots of beautiful nature.” She didn’t want to elaborate at the time, but later she wrote Steve and me a long letter, which described her depression after the disaster, and how she had lost faith in people around her. Not wanting to be spoiled by the events around her, she “decided to smile all the time in order not to worry others around me. Even though the steps are very small, I now feel like being able to overcome the problem of distrusting others.”

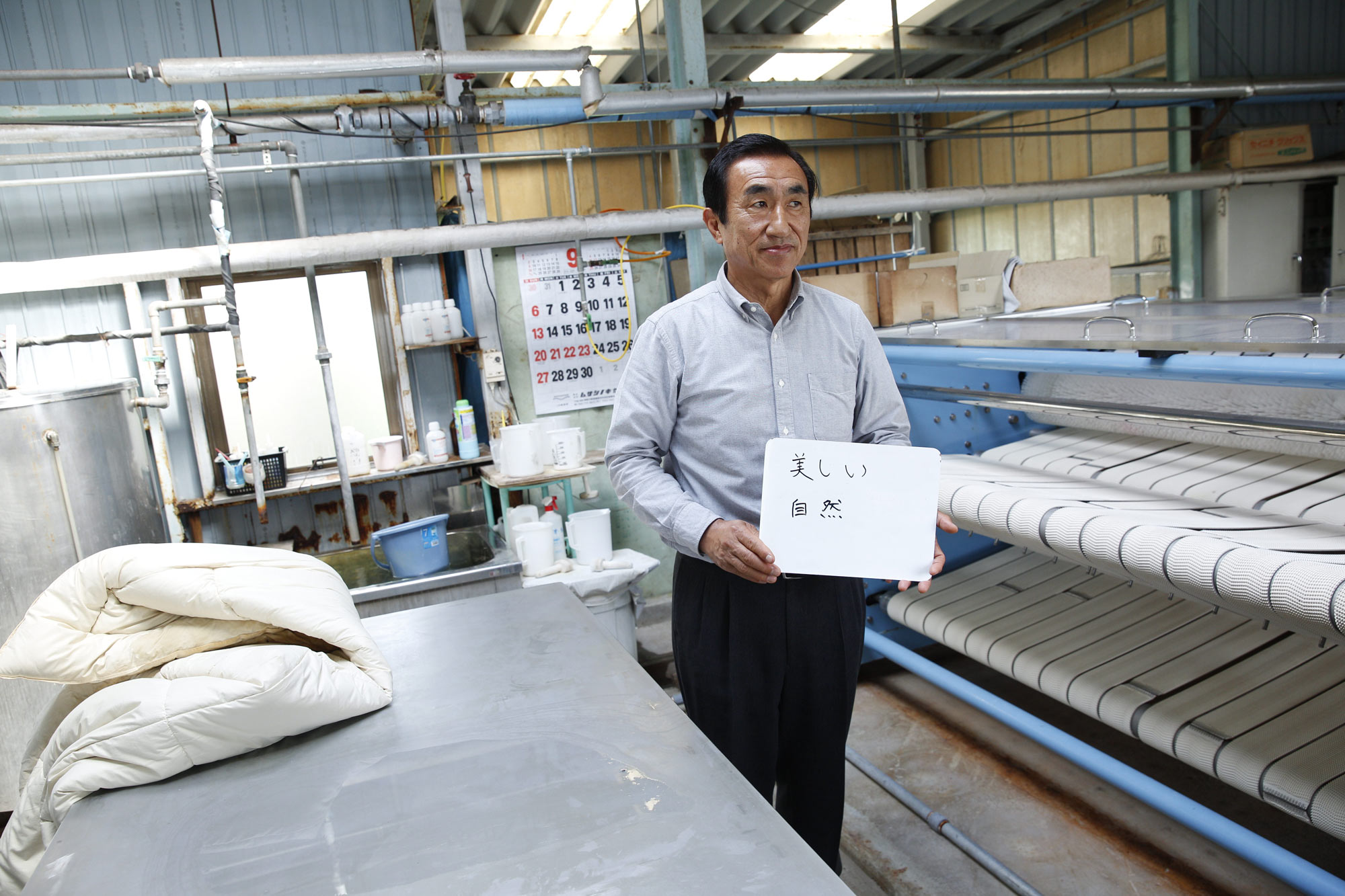

Kiyoshi Watanabe, laundry business owner, returned evacuee

Kiyoshi Watanabe owns a commercial laundry operation in Naraha. Although few local residents have returned, his business is recovering well. Thousands of decontamination workers are doing remediation there and in nearby towns; most of them live in worker dormitories or basic guesthouses, and Watanabe washes many of their sheets and towels.

Before the disaster, he had fifteen employees. Now he has seven. He’s hiring — 70% of local businesses are, he says — but he can’t get workers. “People in their 40s, the hardest-working generation, have children, so they go to Iwaki and don’t come back,” he told Steve. His hope for the region’s future, he wrote, is “beautiful nature.” His fear: “people.”

Takaaki Ide, farmer and factory worker, returned evacuee

Takaaki Ide has now returned to his home in Kawauchi, Fukushima. When I first met him and his family in 2012, they were living in temporary evacuation housing in Koriyama city, about an hour away from their family farm in the Abukuma mountains. One of the first things Takaaki told me then was how he missed the trees that surround his home.

Today, Takaaki and his wife, Yumiko, are happy to be home, though they’ve kept their new factory jobs in the city. “I still collect mushrooms, but the radiation is too high, so we cannot eat them,” he said. He worries about their future: “I worry a little about the nuclear power plant, but more I worry, will my son come home? He’s 28 years old. I worry — will I have good health to keep working?”

Takaaki took me to see a windmill farm on the mountaintop above their farm. This is the energy future for Fukushima, he told me: the soil is contaminated but the wind blows clean.

Masatoshi Ohata, engineer

Masatoshi Ohata is working to design robots that will decontaminate the inside of the Fukushima Daiichi plant. He lives in Iwaki but he brought his grandchildren to go biking at a seaside park in Naraha. His wife, Kumiko, believed the visit should be safe as long as it did not exceed three hours.

Masatoshi wrote, “Please do not forget about the people who are suffering from the damages by tsunami.” As the family walked to their car, he explained his concern that while evacuees from the nuclear exclusion zone receive attention and benefits, including free housing and compensation for their losses and “mental anguish,” evacuees who lost homes because of the natural disaster receive almost no support.

Yukiei Matsumoto, mayor of Naraha, returned evacuee

Naraha mayor Yukiei Matsumoto was one of the first people to move back to Naraha more than a year ago, in the middle of the decontamination process, and eight months before the town officially reopened. He has been a tireless proponent of his home town, and he and his staff successfully fought a national government proposal to put a long-term nuclear waste dump in Naraha. Instead, they have looked for subsidies and other ways to bring new businesses here, and have plans for a new “compact town” urban development, with commercial space and housing to replace homes lost in the tsunami. They also hope to attract evacuees from towns closer to the nuclear plant who won’t ever be able to return to their former homes.

Still, despite his efforts and his optimistic predictions of growth, Yukiei admits that he really doesn’t know how many people will return. “I hope Naraha will become a town where we can see many children’s smiles,” he told me. “Whether they come back home or not, I hope the former residents will become self-supporting as soon as possible.”

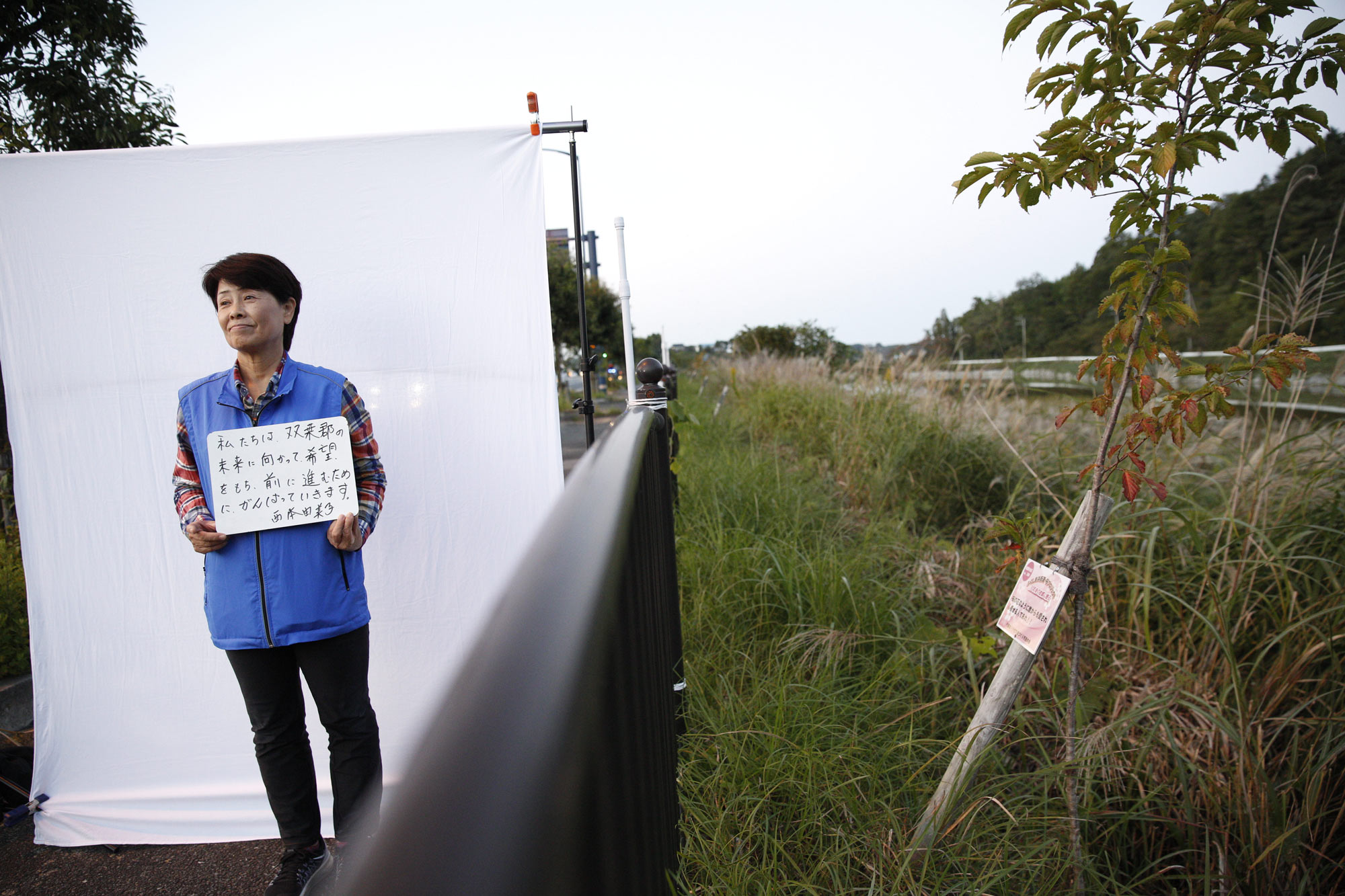

Yumiko Nishimoto, director of Sakura Project, returned evacuee

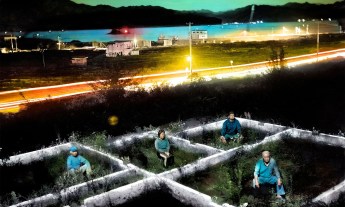

In Japan, the brief-blooming cherry blossom is seen as a symbol of how precious but precarious life is. When Yumiko Nishimoto returned to Naraha, she saw the devastation caused by the tsunami, and thought of cherry trees. She founded the nonprofit Sakura Project, which is working to plant 20,000 cherry trees along the entire 83-mile length of Fukushima Prefecture. Every month, volunteers arrive from across the country to participate in tree plantings.

“Even now, there are people who are not able to return to their hometowns and suffer from many problems including the effects of radiation. We have established the Sakura Project as a symbol of the restoration and determination to create a community,” she wrote. “We would like to pass the memory of this disaster to future generations. We intend to create a bright future with hope for children to come back to this place. That is why we are moving forward.”

Someday, Nishimoto hopes, the trees will bloom every few meters along Route 6, the coastal highway that cuts through the Fukushima Exclusion Zone. She considers the trees as a testament to those who died, and a way to encourage locals and tourists to return.

Yuriko Igari, former guesthouse owner, current evacuee

Yuriko Igari, age 81, lives in evacuee housing in Iwaki city. During a day trip back to Naraha with her son, she visited family graves and the guesthouse she used to run. She told me that she longs for the reconstruction of the town and hopes that what happened there will never be forgotten. Her son told me that he hoped to move back to town soon “under blue skies.” However, in separate conversations, both confessed that they are in the middle of a yearlong argument: Yuriko wants to move back to Naraha to reopen the guesthouse; her son has forbidden it. He fears his mother, who has had two heart attacks since the tsunami, is too frail to survive the stress and work of returning home.

Tokuo Hayakawa, Buddhist monk and anti-nuclear activist, returned evacuee

Tokuo Hayakawa has been an anti-nuclear activist for 45 years and chief monk of the Hyokoji temple in Naraha for 40 years. He opposed the Fukushima Daiichi plant when it opened in 1971, and the 2011 disaster proved what he feared all along, that “human beings and nuclear power cannot peacefully coexist.”

Hayakawa had no qualms about returning to the temple, even though his community has not returned with him. Of 100 families involved in the temple, only five or six have returned, and he is pessimistic that Naraha can ever be a viable town again. “Japan is a small island; we can’t just close an area off. But it’s never been tried before, to bring a whole city back,” he said. Nevertheless, he says he can’t abandon the temple, founded in 1395, despite feeling certain he will be the last head monk there. He had hoped his grandson would take over from him, but now rules out that possibility.

Tamaki Sunaguchi, decontamination worker

Tamaki Sunaguchi works in Tomioka. Last year he worked in the forest division, clearing all underbrush and topsoil in the first 20 meters of any woodland, mostly by hand, and bagging it for incineration. (Forests more than 20 meters from developed areas are left untouched, regardless of radiation levels.) Now Sunaguchi has been transferred to a road decontamination crew. “Sometimes we work in highly contaminated areas,” he says. “I worry about health, but I’ll be home after a year of this.” For now, he’s living in the mountains in Kawauchi, in a worker hotel constructed out of a double-high stack of shipping containers converted to dorm rooms.

Hisao Yanai, former Yakuza, returned evacuee

When the tsunami hit, Hisao Yanai was head of the local Yakuza (Japanese mafia) in Naraha. He says the disaster changed him; he decided to leave the mafia and dedicate himself to helping people. He now owns a Japanese pub in Naraha, but kept many symbols of his former status, including a taxi-yellow Hummer and a stuffed polar bear in the foyer of his sprawling house.

Just after I took this photo, Yanai sat beside the bear. Holding a whiteboard on his lap, he wrote with his one hand about his hope — “solidarity” — and his worry for the future: “how to accomplish the reconstruction of my hometown.”

Ben Takeda, engineer and decontamination supervisor

Engineer Ben Takeda is a Fukushima decontamination supervisor working for the Joint Venture in Tomioka. He posed for a portrait beside the mahjong table in the Maruto office of his friend Kenichi Hayashi, another decontamination supervisor.

In Tomioka, seven miles from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, almost all developed properties are now being cleaned or demolished. Takeda’s job involves traveling from site to site to check in with laborers as they decontaminate homes and commercial properties. The workers remove plants and topsoil for incineration and physically scrub the outside of every building. It often takes a team of six workers a month to decontaminate a single residence, he told me.

Junichi Tanaka, director of disaster prevention for Naraha

As residents consider returning to Naraha, they usually have two primary concerns. Tanaka has no doubts about their first worry — is it safe? Yes, he says. Naraha has been decontaminated and radiation levels in the inhabited areas are close to normal. But he has no answer for former residents’ second fear of whether it will be difficult to live in a ghost town. At present Naraha has three convenience stores, two working gas stations and a few restaurants, but no supermarket, no banks (except for a temporary ATM on a truck) and no schools. The hope is that this infrastructure will return eventually, but it’s not there yet.

Michael Forster Rothbart is a photojournalist based in New York. He spent two years living in Chernobyl, thanks to a Fulbright Fellowship. His TEDx talk and TED Book are based on his After Chernobyl documentary project. His new reportage in Fukushima was funded by grants from NPPA and the International Center for Journalists.