How an elite squad of Tokyo firefighters found the courage to confront the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

On March 18, 2011, Tokyo fire division chief Yasuo Sato (TEDxSeeds Talk: How we put out the fire in Japan’s nuclear reactor) dispatched 119 firefighters to the Fukushima Daiichi disaster zone, six days after a series of explosions tore through the Fukushima power plant following the deadly earthquake and tsunami of March 11. It was a life-and-death situation that required resolve beyond training. Looking back, Sato draws five lessons from that horrific time.

Prepare — even before you’re asked. On the morning of March 12, the day after the earthquake and tsunami struck Japan, the Number 1 reactor at the Fukushima power plant exploded when its reactive core overheated. “Then on the 14th, there was another explosion in Reactor 3,” Sato says. “There are 6 nuclear reactors at the plant, and Reactors 1 to 4 … exploded one after another.” Government teams attempted to cool the reactors by dumping water on them from helicopters, but they couldn’t get close enough; while they made attempt after attempt, radioactivity levels kept rising. As Sato recalls, “Although the Tokyo Fire Department is responsible only for Tokyo, and not for the nuclear power plants, we thought we might get summoned for help, as we are the experts in firefighting and water pumping. So we decided to start our research about how to handle this kind of case.” He and his team determined the amount of radiation they could safely be exposed to; it turned out each firefighter could work a shift of about 10 minutes. “However,” he says, “we could never send out that rescue worker to handle another nuclear case in the rest of his firefighting career.”

A bold plan starts at the bottom. Late on the night of March 17, three days after Reactor 3 exploded and with radiation levels rising by the hour, Sato’s team of Tokyo firefighters got their assignment: Drive to Fukushima and spray seawater through their pumper trucks onto the fuel rods of Reactor 3. Sato took command of a team of firefighters drawn from the 81 fire stations in Tokyo. The mission would be coordinated by a core group of elite firefighters known as the “hyper rescue” squadron. But the captains of that squadron objected to the idea of swapping shifts with less experienced firefighters. “All the captains said, ‘Let us do it,’” he says. “‘We all have been trained for a day like this, and we have good teamwork.’” Some members of the squadron were too young for such a dangerous mission, but they too insisted on going, taking the riskiest orders upon themselves.

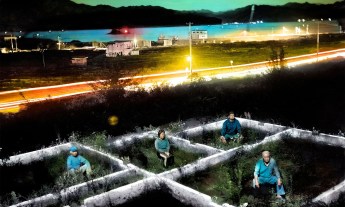

Risk is distributed when more people confront it. When the firefighters arrived at the scene of the reactor, they discovered the path from the sea to the plant was strewn with rubble. Rather than carry their hose by car or truck, they’d have to drag it by hand, more than 800 meters to the sea. “To make matters worse, it is pitch black out there with high levels of radiation,” Sato said. “But I didn’t have any hesitation to give them the go-ahead. We couldn’t afford to retreat and restart with a different strategy, because the level of radiation there was getting higher and higher.” The 119 firefighters split into three teams and worked for 26 hours on site, shouting messages of encouragement through their respirators. Captain Takayama Yukio took command of the team on the front line. And he says: “After I gave the order to start pumping water, the moment I saw water gushing out of the hose, it looked as if it were from heaven: the water from God.”

Make tough decisions. Sato is quick to give credit to strong teammates and leaders on the ground, and he understood his own role: “to make final decisions in a rapidly changing situation that could be fatal any time — to take responsibility.” Someone had to give the final go-ahead to put firefighters in harm’s way — and to recognize that some may not return home, he said. “I am so happy to have been able to send every one of them home to their families.”

Love inspires courage. Sato wrote to his wife to tell her they had arrived, and she emailed him back: “‘Please be a savior of Japan.’ This empowered me and gave me the support I needed,” he says. Meanwhile, firefighter Kei Mishima hesitated to tell his wife that he was heading to the site of a nuclear meltdown. “I couldn’t trust myself to call her,” he says, “so I sent her a casual-sounding email, as if I were heading for a pub for a couple of beers.” Her response: “’You’re a firefighter, so do your bit.’ Sounds a bit bossy, doesn’t it?” he laughs. “In reality it actually was a really supportive push.”

Illustration by Hannah K. Lee/TED.