When Danish chef Thorsten Schmidt was asked to create a banquet in space, the endless tangle of restrictions helped him understand what really matters when it comes to food.

The debate over What People Should Eat has been going on for hundreds of years. But in recent years, the debate seems to have reached a new intensity. Molecular gastronomy has invaded the halls of haute cuisine. A parade of (supposed) experts with diet books in tow all claim to understand the one true science of weight loss and spell out the best diet for everyone from cavemen to French women. People keep looking for newer, better answers to the challenge of eating.

Eating in space, of course, offers its own unique challenges. And while one might have thought that the question had been settled back in the 1960s with the advent of freeze-dried foodstuffs, it turns out that there’s room for innovation over what people should eat there too. When the chef Thorsten Schmidt was asked by astronaut Andreas Mogensen to create a meal for the crew at the International Space Station, he leapt at the chance to apply his culinary imagination to cutting-edge nutrition. But in the process, he discovered not only how mind-bogglingly complicated cooking in space is, but also how food is about much more than mere nourishing the body.

An invitation from afar. There seem to be endless ways we come together to affirm our many cultural identities: We go out dancing, go to the movies, to the ballet, to church. But one of the oldest and most universal is eating together. So what better way to rocket culture into the universe than by holding a banquet in space? At least, that was Mogensen’s idea, when his nine-day-20-hour trip to the International Space Station in September 2015 made him the first Dane to travel to space. He challenged Schmidt to come up with a Danish banquet fit for the nine astronauts onboard. And while Schmidt is known for his playful way of breaching the barrier between food and art with implausible combinations like oak bark ice cream, Mogensen wasn’t after anything so whimsical. He had a more simpler directive: make it delicious, make it space-worthy, make it available within six months — and make it Danish.

The task sounded easy enough. “Dinner for nine, half a year from now, no problem!” Schmidt recalls with a laugh. “The week afterwards, I was just full of ideas — like ‘Space, it’s cold! Let’s do ice cream, let’s do cakes!’ I kind of had a menu in my head — and then a week later the emails start trickling in from [the European Space Agency] with all the rules — and out the window my menu went.”

Terms and conditions still apply in space. To say that there were rules is an almost comical understatement. The actual conditions for the project were unlike anything Schmidt had ever encountered, and he quickly realized the meal would take more time and research than anything he had prepared before. For starters, his food had to go through “autoclaving,” an intensive preservation process using heat and pressure to sterilize food. In addition to killing all microbes and giving the food a long shelf life, this process can slightly change the chemistry and flavor of the meal. The first few entrees he put into the machine melted into an unpalatable mess. But Thorsten learned how to lean into these constraints. So the autoclave was burning sugar in the food? Fine. He made a dish with a flavor profile that complimented the taste and texture of caramelization.

Why you won’t find halibut in space. That was only the beginning. Weight, volume, sterility, durability, ease of ingestion in zero gravity and (last but not least) taste all had to be carefully considered. There were no end to the roadblocks. Schmidt tested a meal containing halibut — but it had a 12% moisture content, above the 10% limit allowed by the ESA for the packaging. He couldn’t get permission to use the space station laboratory freezer for ice cream. The food heater wasn’t big enough to allow the astronauts to bake on board. He had trouble getting permission to seal his Danish soup in the NASA’s drink pouches.

Astronauts: The ultimate picky eaters. Ease of ingestion is a surprisingly prickly issue. Astronauts must eat their meals carefully, one bite at a time. Mixing ingredients while in orbit is impractical and potentially dangerous. A loose glob of wasabi could jeopardize the mission. But even worse was the issue of taste, because it turns out that thanks to a process called fluid shift, astronauts often lose their sense of smell when they get to space. “They cannot detect flavor!” recalls Schmidt ruefully. “I was like, ‘That’s probably not good for me: 80 percent of your perception of taste is the smell!’”

How to eat in zero gravity. There’s a dining table in the International Space Station that in practical terms make little sense; the table takes up room and seems almost absurd without gravity. Instead of sitting in chairs, the astronauts hook their feet into handles — footles? — in the floor around the table so they can stay stationary. But meals are the one time when everyone at the ISS convenes, eats and talks. The ISS designers knew that in the alien environment of space, small moments of connection between the crew would be critical. “Sharing a meal gives us a chance to put aside work and catch up with one another,” said the astronaut Scott Kelly, who recently spent a year aboard the ISS. “Dining together can radically shift perspectives, blurring boundaries just like looking down on Earth from our vantage point does — especially when dinner partners are from all different corners of the world.”

So just what was on the Danish dinner menu? Despite the restrictions, Thorsten eventually did come up with a three-course meal fit for a Dane and his eight companions. The entree was steak, carefully diced into bite-sized pieces, salt-cured to maintain an appetizing reddish color and intensely spiced to compensate for the diners’ impaired sense of smell; this was served with traditional Danish cabbage. For dessert, lemon-rhubarb crème caramel. And for the final course: coffee, with a twist.

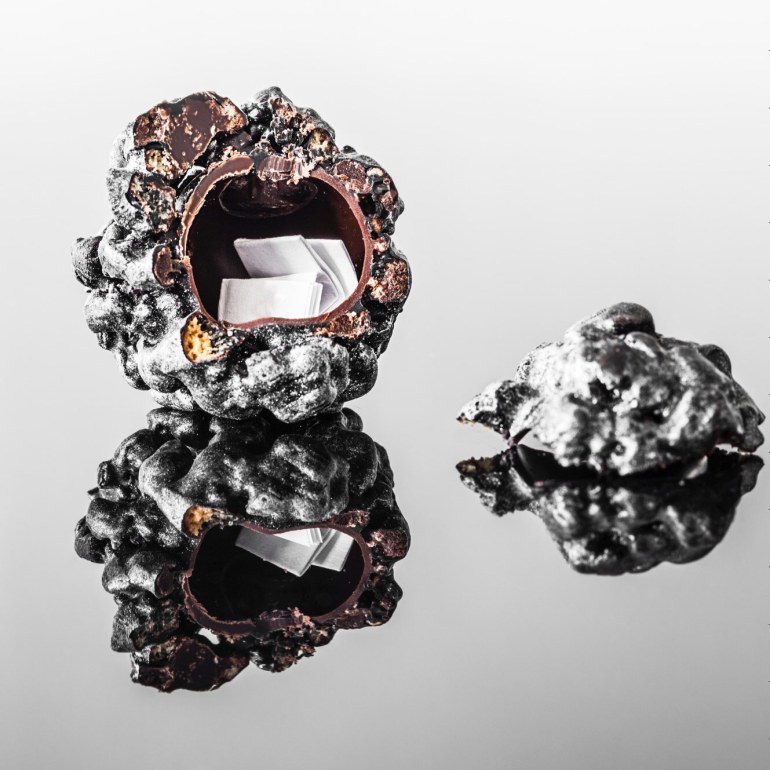

There’s no place like home, even when you’re on the International Space Station. Mogensen did ask Schmidt to include something special and unpredictable, like the clever surprises he comes up with at his own, earthly restaurant. So for the coffee course, Schmidt worked with a chocolatier friend to create an inch-wide “Space Rock” with an ingenious surprise inside. He reached out to the families and loved ones of the astronauts to ask them to write a note to their spacefarers. He then hid these notes inside the chocolates.

According to Mogensen, the astronauts first thought the chocolates were like fortune cookies, with a random message inside. But then, “the second after they started reading, they went quiet, because they recognized the handwriting of their loved ones.” It was quiet but meaningful. “They’re sitting there in the space station in 2015, with no SMS, no email,” says Schmidt. “So we created this special moment.” And it was this moment, far more than the nutritional value of the meal, that demonstrated the power of food as a provider of emotional nourishment. “If we want to go further into space than we are now, we need to go from just surviving to living,” says Schmidt. “This is very important. Food is more than being hungry. It’s about being human.”

All images courtesy Thorsten Schmidt.