This post is part of TED’s “How to Be a Better Human” series, each of which contains a piece of helpful advice from people in the TED community; browse through all the posts here.

When we received the stay-at-home order in March 2020 — I live in California — I came out of the gates pretty darn hot.

“Embrace not being so busy,” I wrote. “Take this time at home to get into a new happiness habit.”

That seems hilarious to me now. My pre-pandemic routines fell apart hard and fast. Some days, I would realize at dinnertime that not only had I not showered or gotten dressed that day, I hadn’t even brushed my teeth.

Even though I have coached people for a long time in a very effective, science-based method of habit formation, I struggled. Truth be told, for the first few months of the pandemic I more or less refused to follow my own best advice.

I think this was because I love to set ambitious goals. Adopting little habits is so much less exciting than embracing a big, juicy goal.

Take exercise, for example.

When the pandemic began, I optimistically embraced the idea that I could get back into running outside. I picked a half marathon to train for and spent a week or so meticulously devising a detailed daily training plan. However, I stuck to that plan for only a few weeks — all that planning and preparation led only to a spectacular failure to exercise.

I skipped my training runs despite feeling like the importance of exercise and the good health it brings has never been more bracingly clear. Despite knowing that it would cut my risk of heart disease in half. Despite knowing that exercise radically reduces the probability we’ll get cancer or diabetes and that it’s as least as effective as prescription medication when it comes to reducing depression and anxiety, that it improves our memory and learning, and that it makes our brains more efficient and more powerful.

Why did I skip exercise despite knowing all this?

The truth is our ability to follow through on our intentions — to get into a new habit like exercise or to change our behavior in any way — actually doesn’t depend on the reasons that we might do it or on the depth of our convictions to do it. It also doesn’t depend on our understanding of the benefits of a particular behavior, or even on the strength of our willpower.

Instead, it depends on our willingness to be bad at our desired behavior.

And I hate being bad at stuff. I’m a “go big or go home” kind of gal. I like being good at things, and I quit exercising because I wasn’t willing to be bad at it.

Here’s why we need to be willing to be bad. Being good requires that our effort and our motivation need to be equivalent. In other words, the harder a thing is for us to do, the more motivation we need to do that thing. And you might have noticed that motivation isn’t something we can always muster on command. Whether we like it or not, motivation comes and motivation goes. When motivation wanes, plenty of research shows that we humans tend to follow the law of the least effort and do the easiest thing.

New behaviors require a lot of effort because change is hard. Change can require a lot of motivation, which we can’t count on having. This is why we often don’t do the things we really intend to do.

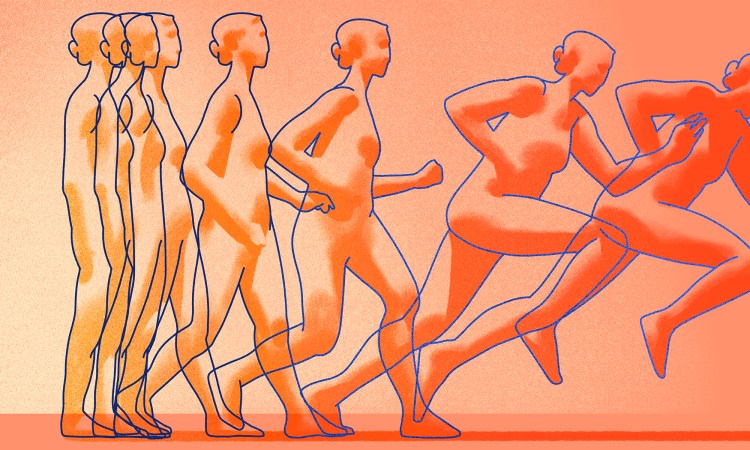

To establish an exercise routine, I needed to let myself be bad at it. I needed to stop trying to be an actual athlete.

I started exercising again by running for only one minute at a time — yes, that’s right, 60 seconds. Every morning after I brushed my teeth, I changed out of my pajamas and walked out the door, with my only goal to run for one full minute.

These days, I usually run for 15 or 20 minutes at a stretch. But on the days that I’m totally lacking in motivation or time, I still do that one minute. And this minimal effort always turns out to be way better than nothing.

Maybe you relate. Maybe you’ve also failed in one of your attempts to change yourself for the better. Perhaps you want to use less plastic, meditate more or be a better antiracist. Maybe you want to write a book or eat more leafy greens.

I have great news for you: You can do and be those things, starting right now!

The sole requirement is that you stop trying to be so good. You’ll need to abandon your grand plans, at least temporarily. You must allow yourself to do something so minuscule that it’s only slightly better than doing nothing at all.

Ask yourself: How can you strip down that thing you’ve been meaning to do into something so easy you could do it every day with barely a thought? So if your big objective is to eat lots of leafy greens, maybe you could start by adding one lettuce leaf to your sandwich at lunch.

Don’t worry: You’ll get to do more. This “better than nothing” behavior isn’t your ultimate goal. But for now, do something ridiculously easy that you can do even when nothing in your life is going as planned.

On those days, doing some wildly unambitious act is better than doing nothing. A one-minute meditation is relaxing and restful. A single leaf of romaine lettuce has a half-gram of fiber and important nutrients. A one-minute walk gets us outside and moving, which our bodies really need.

Try doing one better than nothing behavior. See how it goes. Your goal is repetition, not high achievement.

Let yourself be mediocre at whatever you are trying to do, but be mediocre every day.

Take only one step, but take that step every day.

And if your better than nothing habit doesn’t actually seem better to you than doing nothing, remember that you are getting started at something and that initiating a behavior is often the hardest part.

By getting started, you are establishing a neural pathway in your brain for a new habit. This makes it much more likely that you’ll succeed with something more ambitious down the line. Once you hardwire a habit into your brain, you can do it without thinking and, more importantly, without needing much willpower or effort.

A “better than nothing” habit is easy for you to repeat, again and again, until it’s on autopilot. You can do it even when you aren’t motivated, even when you’re tired, even when you have no time. Once you start acting on autopilot, that’s the golden moment that your habit can begin to expand organically.

After a few days of running for one minute, I started feeling a genuine desire to keep running. Not because I felt like I should exercise more or I had to do more to impress people, but because it felt more natural to keep running than it felt to stop.

It can be incredibly tempting, especially for the overachievers, to want to do more than our designated better than nothing habit. So I must warn you: The moment in which you are no longer willing to do something unambitious is the moment in which you risk everything.

The moment you think you should do more is the moment you introduce difficulty. It’s the moment you eliminate the possibility that your activity will be easy and even enjoyable. So it’s also the moment that will require a lot more motivation from you. And if the motivation isn’t there, that’s when you’ll end up checking your phone instead of doing whatever it is you intended to do or you’ll stay on the couch binge-watching TikTok videos or Netflix.

The whole idea behind the better than nothing habit is that it doesn’t depend on motivation. It’s not reliant on having a lot of energy, and you do not have to be good at this. All you need is to be willing to be wildly unambitious — to settle for doing something that’s just a smidge better than nothing.

I’m happy to report that after months of struggle, I am now a runner. I became one by allowing myself to be bad at it. While you couldn’t call me an athlete — there are no half marathons in my future — I am consistent.

To paraphrase the Dalai Lama, our goal is not to be better than other people; it’s just to be better than our previous selves. And that I definitely am. It turns out that to grow as people, we need only do something minuscule. When we abandon our grand plans and great ambitions in favor of taking that first teeny-tiny step, we shift. And, paradoxically, it is in that tiny shift that our grand plans and great ambitions are truly born.

This piece was adapted from a TEDxMarin Talk.

Watch it here now: