TED Prize winner Sarah Parcak has learned some key lessons about parenthood from her work as an archaeologist. At the same time, becoming a parent has given her new insights into what her work means.

Parenthood is perhaps the most binary experience we go through — there’s an “is not” and then there’s an “is.” For a split moment during labor, you realize, “Oh my god, I am about to be radically redefined as a human being. From now on, I will be known as Mom.” There’s a profound sense of gain when you have a child — and there’s also a profound sense of loss. That process is beautiful and sad at the same time.

Today, I define myself as both an archaeologist and mom to a four-year-old son. My work has deeply influenced the way I think about parenthood — and yet, becoming a parent has also radically changed how I think about my work. Below, five insights.

1. Parenting struggles are largely universal.

Archaeology is the only field that allows you to understand that in 100,000 years and more, our basic humanity hasn’t changed. When I’m excavating an ancient site or studying past cultures, I often find myself thinking a lot about how ancient parents functioned, and what struggles they went through. Because, yes, there are so many major culture differences between us, but the terrible twos are the terrible twos. Did ancient Egyptian parents send their toddlers into time-out? No text I’ve seen speaks to that, but I have read descriptions of schoolboys in ancient Egypt not paying attention and just generally being obnoxious, because — welcome to school — that’s how kids act when they’re bored. My point here: As a modern-day parent, it’s easy to think you’re alone. Yet, all parents throughout time have been dealing with the same crap — literally. Our culture is pretty much the first to do it with the benefit of modern diapers.

2. There’s no “right” way to parent.

The evidence from ancient Egyptian tombs doesn’t show a lot of what we’d recognize as child-rearing. Our sense of childhood — the idea that children don’t become adults until 18 or 21 and should get to play and run around — is a post-Victorian invention. This concept would be completely foreign in most ancient cultures. In ancient Egypt, for example, kids were basically little adults. If you were a girl, you’d learn how to weave, do household chores and take care of younger siblings. If you were a boy, you would work in the fields, help your dad or become a scribe. Remembering this can help modern parents to put things into perspective at times. It makes me skeptical of a lot of the preachiness we see around what it means to be a good parent, particularly in the developed world. It makes it easier to tune out all the online articles about parenting, which are so often chiding and ridiculous anyway. And it keeps me out of the screaming matches that can happen on parenting forums online.

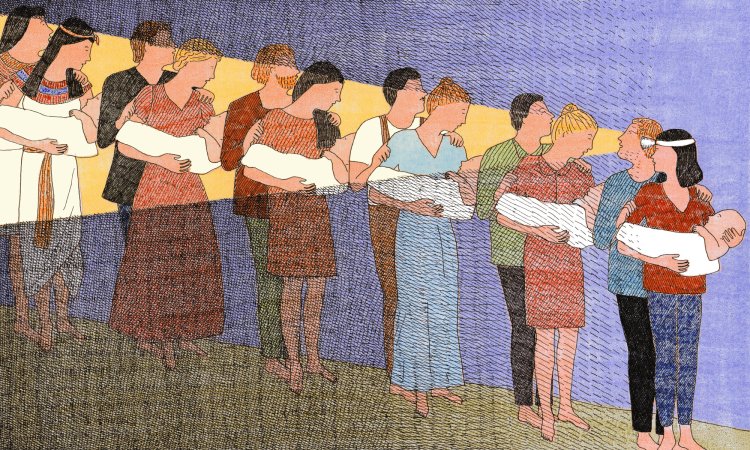

3. There’s wisdom in the village.

Studying ancient cultures shows you just how strange — and ahistoric — our modern approach to parenting is. If you’re a working mom in the United States, for example, and aren’t lucky enough to live near parents or have a partner who stays home, you take your child to daycare or get a nanny. But that’s not the way it was done for thousands of years. In most ancient cultures, child-rearing was a group activity, taken on by parents, siblings, extended family members and even members of the village. That’s still how it is, to a large extent, in modern Egypt. The whole family unit — oftentimes the whole village — is involved in looking after kids. When I travel there for digs, it’s common to see teenage boys watching toddlers in the street or rocking babies to sleep — something I’d be shocked to see in the United States. It’s a different kind of child-rearing, and it feels incredibly healthy to me. I’m not at all trying to say that modern Egypt has everything right — too many women there do not have access to good education and are not able to lead professional lives. Not to mention that I get a lot of respect while traveling there simply because I have a son — something I don’t agree with, even if I recognize it as the shape of the culture. But of course you want your child to be bathed in the love of an entire village! That’s the way it’s been done for millennia, and it’s an approach that I wish many in the developed world hadn’t abandoned.

4. Empathy is key.

As an archaeologist and mother, I feel like I have more empathy than ever for the people of the past. In ancient cultures, infant and child mortality were extremely high — if a child made it to age five, that was a big deal. Before having my son, I don’t think I understood that as more than a fact. Now, I feel it. I remember, shortly after my son was born I went to an exhibition in which they showed photos of an excavated area where children had been buried. I couldn’t take it — it was just too much. Now, on a dig, if I find the bones of children, I find myself asking: how did this happen? How did the parents cope? Such finds physically pain me — as they should! Now, non-parents are perfectly capable of being beautifully empathetic, of course, but being a parent has helped me to better connect to that thing that makes us most human — our ability to empathize.

5. Everyone has their place in human history.

In a world so hyper and self-involved, I think we all feel a little disconnected from the past. We read about history without seeing how it’s directly relevant to us. Many of us live far away from our families, and we don’t have the daily reminders of our lineage in the same way that people do in cultures where three or four generations live under one roof. But being both a parent and archaeologist has shown me how I, like all of us, am a part of the great continuum of life. I hope that growing up in a household with two archaeologist parents gives my son humility and perspective of the incredible accomplishments of past cultures. I hope he’ll listen to the lessons that those cultures have taught us, and that if he’s ever a decision maker, that he will crack open a history book to get perspective. I hope he understands that all human beings — past, present and future — are endlessly interesting. We’re all a part of the long, winding story of human accomplishment.

My son has shown me my place in the human journey — I am his past, and he is my future. Nothing has made me want to save our shared cultural heritage more than that.

With the 2016 TED Prize, Sarah Parcak has built a citizen science platform for archaeology, called GlobalXplorer.org, that invites the world to help locate and protect ancient sites. DigitalGlobe has provided satellite imagery; National Geographic Society has contributed rich content and exploration support; and you’ll provide the analytical power.