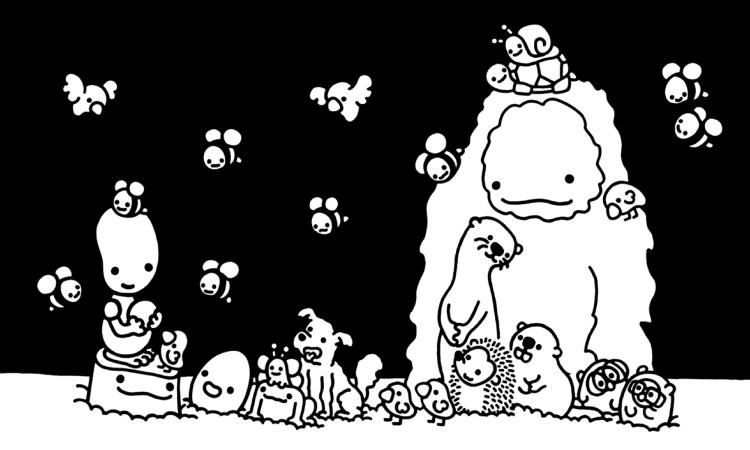

The writer explains how a mix of vulnerability and jokes helped him find his people online and build a supportive community.

Writer and illustrator Jonny Sun is more familiar than most people with the world of social media. A doctoral candidate at MIT, he dedicates his time to studying online platforms and their communities, but he’s probably best known for his Twitter account, which has attracted a large following with its wry, relatable and deliberately misspelled humor (it became the basis for his first book, everyone’s a aliebn when ur a aliebn too). Also a writer for TV shows like Netflix’s BoJack Horseman, Sun sat down to chat after giving a talk at TED2019 in Vancouver, Canada.

TED: In your talk, you mention that you believe Twitter would be a better place if we all worked a bit harder to be vulnerable with each other. How do you do that — be open in that space every day without feeling completely overwhelmed?

Sun: I try really hard not to be a total advocate for social media and a total optimist. That’s difficult because of the realities of the platforms and how bad they are making the world. But for me … I feel like I found an outlet, and I found people who are like-minded. So I know that when I share something there, I will have people who are supportive and who will be able to see that and say, “Oh, that helps me put words to it.”

Part of that has been cultivating this little community over a long period of time where people now know when they see that [vulnerability] from me, they’re not going to make fun of me because they’re like, “Oh, this is part of how he exists online.” Any time you have something you want to do online or you have an outlet, it draws in the other people who see the value of that. That’s good and bad, obviously. For me, when I want to share what I’m vulnerable about because it helps me personally, I also find other people that it speaks to.

TED: In terms of a survival tool kit for this space, for you that’s meant building the community that you want to be in?

Sun: I think so. It’s also a lot of knowing when to not [be there] and knowing when that becomes harmful or toxic for me. Especially around November 2016, it became a place where I was just stuck. You could get caught in [all] the information, right? I realized that was super-toxic. It’s also just having a balance.

TED: When it comes to that balance, are there times when you decide to step back?

Sun: Yeah. I feel like I don’t have a system for that, but I can feel when “Oh, this is going to be bad for me to be on here” and when it is comforting.

TED: You’ve talked about being very open with your online community. For instance, you’ve tweeted about therapy. Do you ever feel like you owe these things to your audience? Or do you feel there are things that you can keep to yourself and you’re in control of what you want to share?

Sun: It’s a little bit of both. I don’t think I owe them, but there’s a trust and a relationship there. It’s not like I ever feel I have to share, but I feel almost compelled to because we’ve built this kind of back and forth. I try to exercise that muscle that tells me, “Oh, this is a helpful thing to share.”

But the other thing I try really hard to do with my identity online is not just keep it one thing, because that’s a trap we have. That’s what the first wave of the internet was: the novelty account, where you’re following this person for a [particular] topic. I think now we’re much more aware that we’re following real, 3D, fully fleshed-out humans. So I’ll go a stretch without sharing any vulnerabilities and just share jokes for weeks on end, but I don’t think people will think it’s out of character. I don’t think people see that as strange because [they know] I kind of do all of it.

TED: When Jack Dorsey spoke at TED2019 about how Twitter users mainly wanted to follow topics rather than individual accounts, did that clash with your experience of the platform?

Sun: Yeah. I thought that was totally wrong, or at least … I don’t think he got the full idea of why people use it. I think there’s this intimate relationship that people foster, especially on Twitter, because it does feel like you’re reading someone’s writing, which is different from seeing their face performing.

I mean, I’m interested in different trending topics and different issues, but I’m interested in those in so far as I can hear what the people that I know online are thinking about them. I don’t want to go on and see a bunch of people talk about gun control. I want to see my friends talk about it and the people that I trust.

TED: You’ve been on Twitter since 2009. In your early life on the platform, was there a tipping point when you realized it was about to become a very large part of your life? Or was there a gradual buildup?

Sun: I think it was a gradual thing. I wanted to share what I wrote, and there was always this idea that I just wanted to find people who also felt the same way as I did or who would appreciate the stuff that I wrote. It was always about finding connection. Then, at some point I remember waking up and being like, “100,000 people see what I write,” and it was really scary. I didn’t tweet for weeks! [laughs] And I don’t think I was paying attention to it that much. It was just more: How do I maintain this connection and how do I write stuff that feels true and that will connect other people?

TED: In terms of it being a place where you live, what do you want to Twitter to continue to be, and how do you want it to change? Where would you like to be living online in five years?

Sun: I think the positive part about Twitter and social media in general is that it is a place where you can find connection and a place where you can find community, and you can find those things that are sometimes inaccessible in person. That’s really magical, and there are special places and there is the optimism and hope of talking to people that you look up to and having them see it.

I think that the original promise of the internet is still there; it’s just that the promise has been polluted by all these other factors. The platforms haven’t stayed true to that being the promise of their service — no one has actually said we care about doing this first and foremost. It’s more like, “How do we get ad revenue?”, “How do we get engagement?”, “How do we sell data to companies?”. When the conceptual promise is different from their actual goals, then we get that divide, and that’s where we are now and everything’s terrible. So I don’t really know.

I think the big things [that need to change] are curbing harassment and abuse, and curbing misinformation and hate speech. Getting all the terrorist groups, Nazi groups, violent extremists, and white supremacists off the platform is the basic thing that should happen. The fact that it hasn’t — the platforms are showing their hand about what they actually care about. And it’s not what the people who are actually hopeful about these internet spaces care about.

TED: It does feel like it was a very utopian proposition, but then as soon as having to make money from it came into the mix …

Sun: Yeah. Or the cynical version is they always just use that utopian promise to sell a product. But I think you can search, and sometimes you get glimmers of those hopeful things. I think those exist. That stuff is worth trying to hold on to.