Desert island castaways have inspired novels, movies and reality TV shows — but no story of stranded humans comes close to being as dramatic or fantastic as that of Bradypus pygmaeus, a peculiar species of dwarf sloth that’s been marooned on a remote Caribbean island for the last 9,000 years.

In 2019, when the world was a more mobile place, I joined a research expedition with the Zoological Society of London to track down this real-life Robinson Crusoe and discover more about its habits and genetics in order to help conserve it. Precious little is known about this critically endangered species, and what I discovered on this trip was a tiny animal with an enormous tale to tell.

Getting to the island of Escudo de Veraguas was the first of many hurdles, however. This tiny, 4.3-square-kilometer speck of land is only 17 kilometers from Panama, but the surrounding seas are wild and unpredictable. Our precariously small fiberglass boat slammed and lurched through the choppy ocean for six hours, ensuring we arrived with stomachs in our mouths and hands like prunes.

The sight of the island helped soothe our rattled nerves — it was an explosion of green, fringed by pure white sand and aquamarine water so clear you could watch the candy-colored reef fish dance amongst the coral without even having to leave the boat. Escudo’s coastal waters are peppered with standing rock formations wearing top knots of the most determined plant life, giving the impression of a wizened greeting party. The island itself is a protected sanctuary, part of the natural heritage of the Ngobe-Bugle indigenous group whose tradition states that the ghosts of their ancestor’s enemies have been turned into these rocky heads.

Other than a few simple wooden fishing huts, where the Ngobe camp for a few months of the year to dive for lobster, the island is uninhabited for the majority of the year. There is no electricity, no Wifi, no sanitation. Upon arrival, I was handed a trowel and told to “make like a cat” on an adjacent beach when I needed the bathroom.

I’d decided against bringing a sleeping bag or mattress, assuming the so-called dry season would indeed be dry and hot. But thanks to climate change, it was neither — and dry is the very last word I would use to describe my experience of Escudo. According to Tayofilu, our wise-old Ngobe fisherman host, this was not normal. In the last few years, he said the weather had changed dramatically and was now “upside down.”

I spent my first night shivering in a large puddle while hurricane-force winds whipped my tent, worrying how the resident sloths were surviving. Sloths are strangely cold-blooded for a mammal; their body temperature fluctuates between 24 to 33 degrees Celsius (or 75 to 91 degrees Fahrenheit). Instead of burning precious calories to stoke their internal combustion engine, sloths use the heat of the sun to warm up, like lizards. This is one of their many ingenious adaptations to survive on their low-energy leafy diet.

Sloths are famously slow — they use camouflage to hide from predators rather than rely on speed to escape — and they’ve turned their lives upside down to hang from hooked claws so they use half the muscle mass of a similar-sized upright mammal, a further power saving that helps them burn less than 100 calories a day. Sloths are energy-saving icons whose laid-back lifestyle has proved extremely successful. After all, they’ve existed in one form or another on this planet for around 60 million years and could certainly teach us humans a thing or two about sustainable living.

Adapting to rapid change is a tough call for any animal, let alone sloths that don’t do anything fast. On top of that, the sloth population on this island is small and particularly vulnerable to low genetic diversity through inbreeding. This makes it harder for them to cope with the kind of accelerated environmental makeover that we humans specialize in creating, such as deforestation or “upside-down” weather. On this trip, our mission was to find the pygmy sloths and collect hair and saliva swabs to assess the extent of their genetic vulnerability.

But first we had to find them, which is never easy.

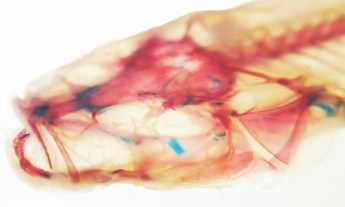

Sloths are masters of camouflage. Their fur has grooves which trap moisture and create tiny hydroponic algae gardens that give them a greenish hue and helps them merge with trees and avoid predators. In addition, these particular pygmy sloths had made our lives harder by taking up residence in mangrove swamps, which are no place for lumbering humans.

Depending on the tide, we were forced to wade either up to our necks in water or thigh deep in sticky, foul-smelling mud as we navigated the tangled web of a million mangrove roots. This had to be done while wearing giant industrial rubber boots to protect us from stepping on the resident stingrays. As we wobbled through the mud, we were also warned to watch where we placed our hands; the trees were decorated with an unusual profusion of eyelash pit vipers — deadly yellow noodles whose bite could easily prove fatal given how far we were from a hospital containing anti-venom.

I have never felt so intrepid. But it was all worth it when we finally spotted our first sloth: a bedraggled greenish grey huddle clinging to a mangrove branch about 15 feet in the air. It was a young adult, weighing in at little more than two kilograms (or around 4.4 pounds), so it was half the mass of a mainland Bradypus variegatus sloth, the three-toed sloth most people are familiar with, and twice as cute.

Pygmy sloths are a great example of what’s known in zoology as “the island rule.” This natural law predicts that animal populations isolated on islands have a tendency to either get bigger (if the threat of predators is removed) or smaller (if resources are limited).

Well, ever since Escudo separated from the mainland around 9000 years ago, the population of Bradypus variegatus that became isolated on the island have been shrinking. The hummingbirds, meanwhile, have supersized — the island is home to a sub-species of the rufous-tailed hummingbird that’s bigger than its mainland cousins. one of the largest known species. Escudo is like Alice in Wonderland, home to dozens of species including a fruit-eating bat, an armoured rat and a worm salamander that are found nowhere else on earth. It is little wonder it has been compared to the Galapagos.

What makes these pygmy sloths even more enigmatic is they have left the forest to hang out in the mangrove swamps. Like most of the pygmy sloths’ habits, why they do this on Escudo is a mystery. It can’t be to escape predators, as there are just as many hungry boas in the mangroves as there are in the forest. While the sloth’s staple food — the leaves of the Cecropia tree — is in plentiful supply in the forest, on this island they prefer to eat mangrove leaves, which may be the draw.

Bryson Voirin, a researcher from the Max Planck Institute in Germany, thinks the sloths may be visiting the swamps to get high. While studying sleep in sloths, Voirin compared Escudo’s pygmy sloths with their mainland cousin and discovered the island’s pygmy sloths spend much less time in REM sleep. In fact, the difference in the intensity of their brain waves resembled the changes in neurology that typically follow the consumption of Valium-like sedatives. Benzodiazepine-like compounds have been found in certain plants, including mangrove leaves. If Voirin’s hunch is right, the pygmy sloths might not just look stoned — like all sloths do — but they really are stoned.

In the case of the pygmy sloths, narcotic mangrove leaves might also help aid their digestion. Bradypus variegatus sloths have a famously slow digestive rate — it can take them up to one month to process a single leaf, which gives their livers time to process the leaf’s toxins and not become overwhelmed and their intestines time to extract what little nutrition they contain. Since the rate of digestion generally scales with an animal’s size, the shrunken pygmy sloths would have a quicker digestive process than their mainland cousins. Sedative supplements could help slow their metabolism and the passage of their food, keeping them from poisoning themselves or starve.

In the future, Diorene Smith, the Panamanian vet in charge of the ZSL mission, hopes to find out more by taking a botanist to the island and investigating the sloth’s diet. This information, along with the genetic material we collect on this mission, will help unlock valuable secrets of their peculiar life. “You can’t save an animal you know nothing about,” she told me.

Time is running out for this pygmy sloth. They may have spent the last few millennia hanging like happy hairy hammocks from the mangrove branches and quietly getting baked, but Panama is now developing at an astonishing rate, thanks to lucrative partnerships with China and the US. The arrival of a new road opening up the north has prompted a gold rush of development along one of the last stretches of wild Caribbean coast, and Escudo is in their sights.

Then there is the curse of cute. The trend for sloth selfies is already a plague on Instagram, with numerous charities campaigning against tourists having their photo with captive sloths, snatched from the wild. The ZSL team are concerned that tourists coming to the island will also want to have their photos taken cuddling the pygmy sloths. They are pretty easy to catch after all, but those fixed smiles are deceptive.

Wild sloths are solitary creatures that can become dangerously stressed when placed in captivity, as was discovered not so long ago. In 2013, an American private animal collector attempted to steal 8 pygmy sloths from the island in his private jet to stock his personal zoo. To get his hands on this rarest of all sloths, the collector claimed that they were being taken for their own good, to become part of a captive breeding program — a plan that conservationists have said could never work for a delicate species like this. Fortunately, the sloth heist was prevented by angry locals at the airport, but not before two of the sloths had died of captive stress.

On our last day on Escudo, a boat-load of tourists rocked up to bob about in its turquoise waters drinking cocktails. Diorene told me this is happening more and more — the island is being invaded. She is frightened. As a resident of Panama, she has seen firsthand the lightning speed at which development can devastate an environment and reach a point where there is no turning back.

My heart sank, and I felt the prickly flush of fear. Escudo had whipped my ass — it is as brutal as it is beautiful — but I felt hugely protective of it. Tourists can drink cocktails on a thousand other white-sand beaches in Panama but please not on Escudo. I want this island to be protected from the corrosive tide of capitalism and remain a haven for its outrageously weird wildlife.

I have spent the last 10 years documenting the strange lives of the planet’s six extant species of sloth. The pygmy sloth of Panama is not just the smallest and rarest but, with its enigmatic mangrove lifestyle, the strangest of the bunch. Our research trip was a success, and we were able to collected hair and saliva from a dozen or so individuals. Hopefully the data, once analyzed, will reveal some of the secrets of these enigmatic creatures and help the Ngobe people and ZSL conservation team to continue to protect them.

To me, this world is a far richer place with these pint-sized stoners dangling peacefully in the mangroves. But like Diorene, I fear that our busy planet may be moving too fast for the world’s slowest mammal. If only we could slow down enough to appreciate the pygmy sloths’ steady, sustainable lives, we might learn a few lessons about how to save energy — and the beautiful planet we both call home.

All images: Lucy Cooke.

To learn more about pygmy sloths and support the ZSL EDGE campaign to save this critically endangered species, visit the Edge of Existence site.

To see more photos of these sloths and others, check out Lucy Cooke’s Sloth Appreciation Society Calendar — the 2021 calendar is now available.

Watch her TED Talk on sloths now: