Massive protests didn’t stop the Dakota Access Pipeline from being built, but we should try to measure their success in other ways — by the lessons learned and by all the people and communities empowered, says tribal attorney Tara Houska.

“You could feel the energy in the air. You could feel the resistance happening,” said activist, attorney and Couchiching First Nation citizen Tara Houska in her talk at TEDWomen.

From April to December 2016, thousands of people had joined together in Standing Rock, North Dakota, to demonstrate against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) — an underground oil pipeline set to be built through Native lands. (This occurred after it was rejected by a nearby non-Native community). On December 4, they cheered when the Army Corps of Engineers announced work would stop until an alternate path was found. But the celebration didn’t last long. In January 2017, president Donald Trump signed an executive order allowing DAPL construction to continue.

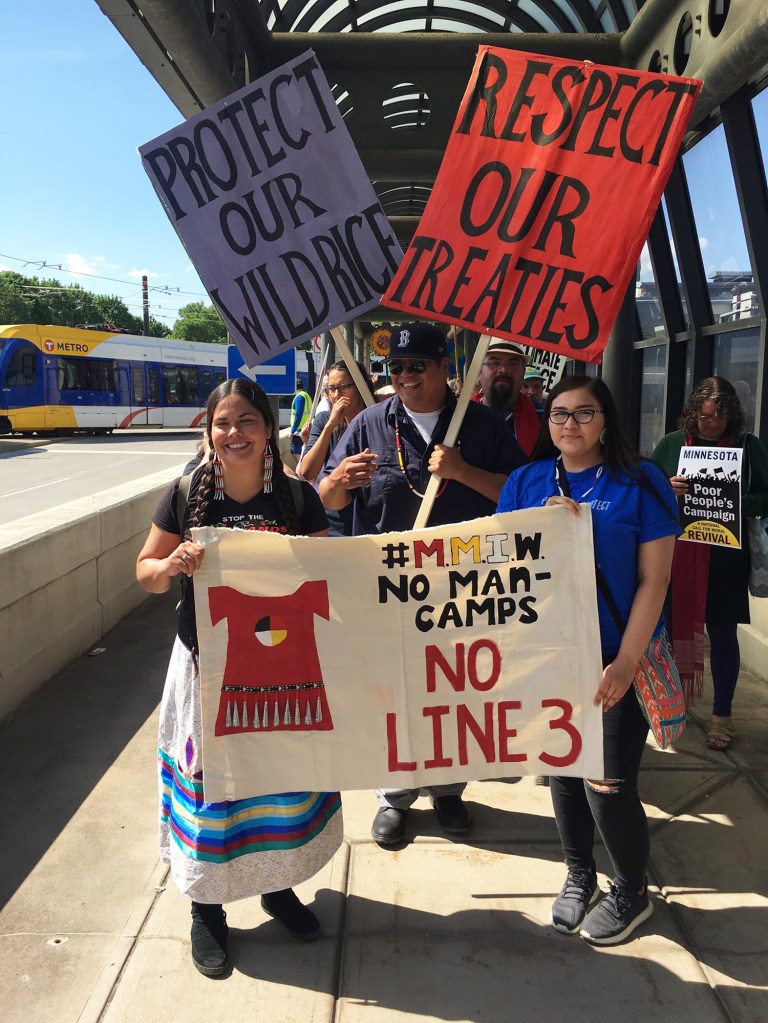

Were the protests all for nothing? No, says Houska. In fact, she’s working now on another protest — the efforts to block Line 3, a pipeline across Native territories that would carry nearly one million barrels of tar sands a day through the headwaters of the Mississippi River to the shore of Lake Superior. TED spoke to Houska about the impact of Standing Rock, the state of Native resistance today, and the best ways for allies to show their support.

Q: What has been the lasting impact of the #NODAPL movement?

Houska: It stands as a moment where we saw so many people around the world becoming aware of indigenous peoples, how indigenous rights are being violated today, and the imminent threat of climate change. And it was a moment of solidarity and resistance in that people were willing to take a stand with us. It also made people recognize the power of community organizing and of a ground fight, and that these actions can cause ripples that are felt all the way at the top. Since then, we’ve seen more and more resistance camps springing up against different extractive industries.

Q: How did #NODAPL affect activism on a global level?

Houska: I think a lot of the so-called “big greens” became aware that indigenous peoples can and should lead a movement, and that the voices of those impacted by extractive industries should be included in the conversation. Up to that point, we’d only get included at the last minute, or at least that’s how it felt to me.

Q: What were the takeaways from the protests?

Houska: There were many. I hope those engaged in the struggle recognized that tribal governments are very different from tribal people. Tribal nations are not always in alignment with their people, because they have different interests at stake. A broader lesson was that there are hundreds of indigenous nations with unique interests and struggles. We’re not a monolith.

Another lesson was that we need to be proactive rather than reactive. The call for help in North Dakota came as the construction of the pipeline began. Now, in the Bayou Bridge struggle in Louisiana and in the Line 3 struggle in Minnesota, we’re trying to be much more proactive by fully engaging in the regulatory, legal, legislative and public-opinion processes as well as in the ground fight itself.

Q: How important a factor was social media in the movement?

Houska: The resistance against DAPL was not something that always made the mainstream news. But on social media, thousands of people were able to see what was happening on the ground. They saw how attack dogs were used on humans, how water cannons were used on people in subfreezing temperatures. Images and videos of these events were shared on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. In September 2016, President Obama was even questioned in Laos by a student there about DAPL. He was caught completely off guard. And the student had heard about the pipeline through a Facebook message.

Q: How did divestment become a strategy used by protesters?

Houska: There came a point in North Dakota when we were physically blockaded and unable to go and stop the construction of the pipeline. Many folks were asking, “How do I help? What can I do?”– especially people who weren’t able to stay at the protests. So divestment became a tactic. We basically said, “Here are the 17 banks that are funding this project. Is your money sitting in these banks? Pull it out. Is your pension fund banking with this institution? Pull it out.” We looked at institutions and said, “You have our money, so we’re holding you accountable for allowing these companies to continue to do these activities and engage in these kind of practices.”

It was incredibly successful, and it’s an ongoing tactic. The language of money is one that the fossil-fuel industry definitely listens to. And it’s one that the banking institutions clearly listen to — their entire existence is facts and figures. We’re recognizing our power as consumers and that we have agency to do something in this larger narrative of climate change.

Q: How do you personally gauge if a protest movement is successful? At Standing Rock, for example, pipeline construction still went forward.

Houska: You can gauge it by a number of different things. Obviously, our goal is to keep fossil fuels in the ground and to move away from using them since they’re a cause of climate change. But another way to gauge success is to look at the level of involvement by people who feel empowered. I see more and more of our youth realizing their own power, standing up and fighting for their futures. That’s a success in and of itself. You can also see success in the actions of financial institutions and in the explosion of renewable energy and the public push to move America towards a form of energy freedom that doesn’t include fossil fuels.

Q: Besides pipelines, what are the major issues of concern for Native activists today?

Houska: One of our most pressing concerns is intertwined with the extractive industry: camps pop up to build energy projects, leading to an influx of men into rural areas. Thousands and thousands of Native women are missing or murdered in the US and Canada, and there’s been little justice sought by the American government or received by the women’s families. Because Indian Country is in rural areas, we are impacted by the fossil fuel industry most heavily and we experience these crimes first and worse. It’s a massive issue that has yet to be addressed.

Another concern is the attempt to dismantle the Indian Child Welfare Act. This is a law that tries to keep Indian families together when out-of-home placement occurs. In Minnesota, for instance, the out-of-home placement rate for a Native child is 12 times greater than for a non-Native child. In October 2018, a federal judge in Texas said the act was unconstitutional. (Editor’s note: The decision is being appealed.) To undo it would be to undo the whole of federal Indian law. We would not hold “special rights” any longer — and I don’t think it’s really “special rights”; it’s simply the recognition that we are sovereign nations that were here before the founding of the United States. This is definitely very, very high on our priority list.

Q: For people who want to support indigenous activism, what would you suggest they do?

Houska: I’d recommend figuring out what tribes are up to around you. If you want to learn more or support people on the front lines of the Line 3 pipeline efforts, you can go to stopline3.org. If you’re interested in other Native struggles or issues, do some research to find out who is already working on it and try to support them in a real way.

Regardless of the issue, maybe your support is monetary, or maybe it’s your physically going to a place and standing with and listening to the people who live there. Or it could mean developing your own divestment efforts and approaching institutions like your universities and city councils. These are all real things that you can do to help. You can also contact your elected officials and ask them, “Are you upholding treaty rights?” Most elected officials in America have either no idea who Native people are or have very little experience with them. It’s a shame, and it shouldn’t be that way.

Q: Any final thoughts you’d like to share?

Houska: I would encourage folks to be brave, to be bold and to recognize that we’re in very urgent, desperate times. These issues — issues of climate change and protecting our earth’s resources — should not lie just on the shoulders of Native people. It should rest on all of our shoulders. Standing in solidarity is something we should all aspire to do and we can do if we work together.

Watch Tara Houska’s TED talk here: