So much has disappeared from the islands of my childhood. Will the paniolo be next?

My infatuation with Hawaiian cowboys began on O‘ahu’s North Shore, a quiet district enlivened by big waves and show-off surfers. On Sundays we country kids would sneak to a rugged polo field laid out parallel to the beach. We’d ogle the Honolulu high society gathered under big white tents — men in navy sport coats and women in high heels, who’d sip champagne while they watched the matches. Prince Charles played there, and some jet-setting Argentines, but the polo players we rooted for were paniolos. They’d come from Maui and the Big Island, and they’d wield their mallets like ancient Hawaiians did their spears. Some were the descendants of missionary families or the scions of families who owned Waikiki hotels. Others were Native Hawaiian horsemen in a class of their own. Our favorite was Tuna Sampaio, a beefy local whose Pidgin English cursing once caused Prince Charles to dismount, throw his glove on the ground, and stomp off the field.

where the Clint Eastwood cowboy is all piss and pistol, the Hawaiian paniolo knows his flower species as well as his cattle breeds.

Of course, most American kids have, like me, been raised on cowboy worship. But where the Clint Eastwood cowboy is all piss and pistol, the Hawaiian paniolo is possessed of a gentle soul, a lovely language, and a music that is more soft-and-sweet than achy-breaky. The paniolo knows his flower species as well as his cattle breeds. The paniolo weaves blossoms into leis he then wraps around his hat. He teaches his horses to swim in the ocean and to pick their way through sharp fields of lava.

Increasingly, this proud paniolo is threatened with extinction. Once-mighty cattle ranches are struggling in a global economy, and all-terrain vehicles offer ranchers a cheap alternative to bunches of cowboys, each with a string of horses. Tourism long ago replaced ranching as one of Hawai‘i’s biggest businesses, and most visitors prize golf courses more than grazing fields.

All have disappeared from the islands in a generation: certain small native birds, lobsters in the coral reefs, Japanese fisherman who throw their nets at dawn. What about the cowboys?

So many things have disappeared from the islands in a generation: certain small native birds, lobsters in the coral reefs, Japanese fisherman who throw their nets at dawn, sugar-cane fields and the thrice-a-day mill whistle, the manapua truck. (This was our version of an ice cream truck, which roamed the streets after school and sold pork bao for a quarter. Manapua is a contraction of the Hawaiian mea ʻono puaʻa, or “delicious pork thing.”)

What about the cowboys? On a long-awaited trip to the Big Island, I decided to go looking for them.

I arrive in Honoka‘a, a coastal village 38 miles west of Hilo, on Memorial Day weekend. The town’s 1920s buildings — which have Western-style false fronts and covered boardwalks — house art galleries, real-estate offices, the Hula Moon boutique, Teresita’s Filipino Store, and the People’s Theatre. (Its marquee announces, “Now Playing: Kung Fu Hustle.”)

This weekend, the town is hosting the annual Hawaii Saddle Club Rodeo. The event is kicked off Friday night by a parade on Honoka‘a’s main drag. Outside JJ Meatmarket, the hundreds of milling locals range from shirtless surfers in board shorts to families in yoked shirts and cowboy-hats-banded-with-ferns. A few women flit by in merry widows and hot-pink boas.

I’m in luck, because the Grand Marshall of the parade is Jamie Dowsett, the father of a high-school friend. Flanking the 80-year-old patriarch on horseback are his handsome sons, in starched white shirts. His wife Queenie, a hula dancer and former Hawaiian TV star, waves from her palomino. Granddaughters in chartreuse jackets follow on their mounts. A pickup truck is loaded with hay and more progeny, followed by two in-laws trailing in an ATV. (They are the pooper scoopers.)

The following day at the Honoka‘a arena, a dusty corral just uphill from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Dowsett is on his horse again, waiting in “the box” — a six-foot wide pen between two steel fences. Next to Dowsett is a chute packed with calves; on the other side waits his nephew, Joe Ka‘ai.

Dowsett gives a terse nod and the gate to the chute flies open. With a thundering of hooves, the race begins. A poor calf faces the impossible challenge of outrunning two muscular horses and their whirligig-armed riders. Joe, the “header,” leans over his saddle horn, slings a lasso over the calf’s head, and tightens the noose. The pressure switches to Dowsett, “the heeler,” who swishes his lasso, reads the bucking calf’s dance, and manages to ensnare a back leg. The pair is penalized five seconds for leaving the other back leg free.

Dowsett soon joins me and the entire clan in the stands. He’s still dressed for the ring, in a Southwestern print shirt and a felt cowboy hat with a pheasant-feather hatband. His thumbs and forefingers, thickened by arthritis, are taped for roping.

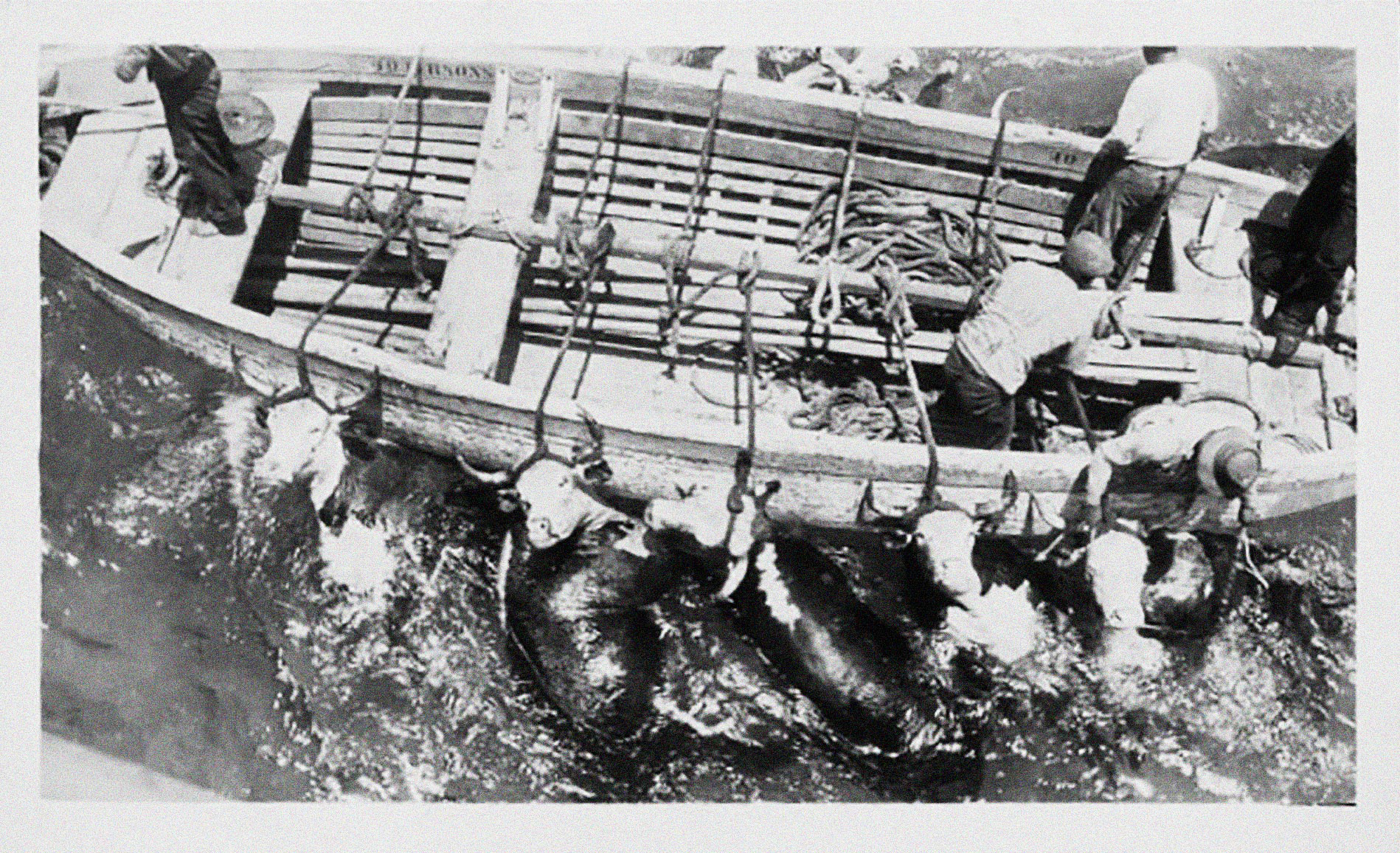

“In the old days, cattle were loaded by water. Paniolos would use big draft horses that had broad shoulders to float easier. The cowboys would swim three cattle out at a time, tie them onto longboats, row out to the ship, and swing the cattle up onto the deck.”

“We use to train our horses in the sea water,” he answers, when I ask what makes paniolos different from their mainland counterparts. “We would ride the horses in water up to their chests. First, it was easier on the man—the horses wouldn’t be able to buck so much. Second, the horses would tire quicker. Third, it would teach the horses to swim. In the old days, cattle were loaded by water. Paniolos would use big draft horses that had broad shoulders to float easier. The cowboys would swim three cattle out at a time, tie them onto longboats, row out to the ship, and swing the cattle up onto the deck.”

Dowsett begins to reminisce. One of his favorite moments, he says, came at Pu‘uwa‘awa‘a Ranch, on the slopes of Hualalai. “All the guys were Hawaiian,” he says. Many locals, he adds, call the distinctive location “Cupcake Hill,” because its corrugated cliffs make it look as though it was cooked in a ridged paper cup. “But the Hawaiian name Pu‘uwa‘awa‘a actually means furrowed hill.

“That was a different kind of ranch — in the lava fields,” he remembers, his voice lifting. “We’d ride single file, up the hill, and the guys would be singing in Hawaiian.”

After a week of watching rodeo events, chasing bulls myself, and trying to get cowboys to talk, I head to the summit of Mauna Kea to forget about cowboys for a bit and focus on the island itself — vast, volcanic, and hard to get a handle on. Mauna Kea — or “white mountain” — looms large in paniolo song and lore, and it has loomed over me throughout my week here. I meet a guide at the Humu‘ula Sheep Station, a motley collection of wooden buildings on the lower slopes of the volcano. Mark Twain once stayed here, as did the literary adventurer Isabella Bird and the Scottish botanist David Douglas. (He’s the namesake of the Douglas Fir.) I grab a pile of clothes suitable for the Arctic and jump in a van with seven others.

We emerge into an alpine desert. This glacial moraine is the closest material on Earth to Mars.

As we head through the cloud layer, a thick fog deprives us of all sense of time and place. Then we emerge into an alpine desert. The guide tells us that this glacial moraine — lava pushed rough and raw from the earth, ground down by glaciers, deprived of rain, unsoftened by vegetation, and subjected to harsh ultraviolet radiation — is the closest material on Earth to Mars. We pass the sacred Lake Waiau, which was the resting place for the umbilical cords of newborn kings and queens in ancient Hawaii. We enter the domain of Poliahu, the Hawaiian goddess of ice.

This is the best star-gazing spot on earth. It stands above 40 percent of the Earth’s atmosphere and far, far away from the bright lights of any urban metropolis. And it benefits from an unusual weather condition known as “trade wind inversion,” which keeps the sky clear 325 days a year.

Scattered across the 13,796-foot high summit are more than a dozen telescopes, housed in observatories that look variously like cool siblings of R2-D2 and truncated cafeteria trash cans. The “Keck Twins” are the most powerful telescopes on earth; Japan’s Subaru Facility houses the world’s largest single-mirror optical telescope.

As awesomely powerful as these symbols of Science are, my attention is drawn to an even higher summit a few hundred yards away. This is Pu‘u Kūkahau‘ula, a cinder cone still claimed and managed by Native Hawaiians. A footpath snakes up to its peak, which is topped with an offering bier. I am curious, but I am also fricking cold — with three layers of shirts, a fleece, a hooded parka, and wool mittens, I am still chilled to the bone. I’m as wary of Poliahu as I am of altitude sickness, and I know that Native Hawaiians hate haoles that just go trooping all over their turf. So I stay put.

The sun slips below the horizon. Constellations begin to emerge. For the first time ever, and with my bare eyes, I see the Southern Cross, the asteroid Ceres, and Hokule‘a, the “star of gladness” that originally guided the Polynesians to Hawaii.

Back in the van, the strains of “Over the Rainbow,” by the late Israel Kamakawiwo‘ole, fill the stunned silence. The song is an unlikely mix of innocent joy and world-weary chagrin, by a 700-pound Hawaiian who sang in a tender voice while strumming on an infinitesimally small ‘ukulele. Other songs on the CD lament the losses of Native Hawaiians — babies lost in tidal waves, native lands lost to endless resorts, fathers lost to heart attacks and broken hearts. Brother Iz himself died shortly after recording the medley, and he never heard it played. He was only 38 years old.

Suddenly, I am swept by melancholy. I am on top of the world — and despite the barrenness of the landscape and the eerie telescopes and the falling darkness and the frigid air, I do not want to leave. I can’t help but think about the paniolos I’ve encountered — Harry Nakoa, who’s found a living in raising horses; the Richards brothers, who stubbornly find ways to keep their Kahua Ranch afloat; and Jamie Dowsett’s granddaughters, one a nurse and the other accountant, who ride in rodeos and invite me to join a roundup. And I think of little Ka‘ili Brenneman, an eight-year-old who ropes every fence post in sight and promises to grow up to be a cowboy.

Suddenly, an enormous white bird swoops down into the beam of my headlights. It is a pueo, a short-eared owl both endemic and endangered on the islands.

By the time I’m off the mountain and driving back to Waimea, the Big Island sky has turned to obsidian. Suddenly, an enormous white bird swoops down into the beam of my headlights. It is a pueo, a short-eared owl both endemic and endangered on the islands. It was worshipped as a god by ancient Hawaiians and revered by families as an ‘aumakua, or guardian spirit. As a teenager, I believed that a pueo who hung out on the telephone wires of the dark country road leading to my house was my own ‘aumakua. When I’d come home late at night, long after my mother had given up on me and gone to bed, he’d be there, taking flight as I drove by in a rusty Datsun.

I stop. As suddenly as the pueo appears, it disappears, its long wings rowing off into the liquid dark. I cut my headlights, wanting to keep it with me. The stars are thrown into brilliant relief by the black sky.

Jamie Dowsett’s voice drifts back to me, as I continue my drive along fields he knows so well. “We would ride by moonlight sometimes,” he said to me that day at the rodeo. “It was cooler at night, so the cattle wouldn’t get overheated.

“One morning, we started at 4 a.m. — 30 cowboys riding up the mountain. We split into three groups and headed up three different hills. As the sun started to come up, the metal on the spurs caught the light, and all over the mountain you could see the flashes.”

Author’s note: This is an excerpt of a longer piece that ran in National Geographic and it has been adapted for TED Ideas.

Featured image of cowboy at Paniolo Heritage Rodeo-Saturday, Mauna Loa, Hawaii by Kate Gardiner/Flickr.