As I researched my book, Your Fatwa Does Not Apply Here: Untold Stories from the Fight Against Muslim Fundamentalism, and spoke with people in countries from Afghanistan to Mali, I discovered that just as the personal is political, the political is always personal. This has been the case in my own life as well, and it’s why I made the decision to begin my TED Talk, When people of Muslim heritage challenge fundamentalism, with a personal story from June 1993, set against then escalating violence by non-state fundamentalist armed groups in Algeria.

The story recounts the day unknown visitor(s) showed up outside the Algiers apartment inhabited by my father Mahfoud — an Algerian professor known for his stand against extremism. When the local police station did not answer, I found myself — then a bookish law student visiting for the summer — standing ridiculously inside the door we had refused to open, holding a kitchen utensil.

Could I protect my father from the Armed Islamic Group with a paring knife?

1993 was a time when Algerian intellectuals were killed by the armed groups battling the government nearly every Tuesday morning — on “Black Tuesdays,” as the day came to be known. On that particular Tuesday we were lucky, and whoever was outside went away. It might have been an innocuous visit transformed into terror by the context. It could have been death squad interruptus. Luckily, my father had recently installed a metal door in the wake of killings of Algerian intellectuals like the erudite writer Tahar Djaout or Mahfoud Boucebci, one of Africa’s leading psychiatrists.

Could I protect my father from the Armed Islamic Group with a paring knife?

My own morning of minor terror inspired my work to support those in Muslim majority contexts who continue to defy fundamentalists at risk of their lives, with little international support. My own experience was nothing compared to what has happened to other families. Just one Tuesday before our unexplained encounter, the brilliant sociologist Mohamed Boukhobza was tied up in front of his daughter and had his throat cut, at home in Algiers.

Humbled by such suffering in the battle waged by people of Muslim heritage against fundamentalism, I struggled with whether to tell my own story. I never wanted to exaggerate or overemphasize it. But the personal narrative explains why a law professor at a U.S. university would write a book like this. And it is the small window through which I came to see — and now hope others will see — just what risks entire families take when someone makes the leap of conscience to defy the likes of Boko Haram or the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS).

The most touching response I had to my tale came from an academic in northwest Pakistan, an ardent opponent of fundamentalism and terrorism who related to my father’s story. Vigorously affirming that he — like Mahfoud — would refuse to be silent despite the fact that, as a devotee of non-violence, he faced a terribly threatening environment, he added: “I do not have a paring knife even.”

After doing years of fieldwork researching Muslim resistance to Muslim fundamentalism, I am convinced that personal details can wake us from the numbness produced by the “third world body count,” the impersonal way in which the huge number of civilian casualties in places like Somalia and Afghanistan are so often recounted only as a passing statistic.

We have to learn from the past so we better support those who today carry on the struggle against intolerance in Muslim majority contexts.

For example, just this month I had a wonderful Ramadan dinner at the home of the family of Algerian law student Amel Zenoune-Zouani, who was murdered in January 1997 by the Armed Islamic Group (GIA). The holy month is a tough time for them, because that is when they lost Amel, only 22 when she was killed. Nonetheless, Amel’s sisters worked hard to prepare a feast – shorba (soup), bourek (meat pies), fish, salads, and at least seven different kinds of cake — all to try to cheer up their mother. The ghost of fundamentalist violence still tries to haunt their house. But the family’s Ramadan dinner was itself a kind of resistance.

I think telling individual stories like this can make a difference, both in the way people around the world view Muslims, and in the way they respond to those who put their lives on the line to stop the jihad. More than any academic analysis I can offer, sharing these lived experiences helps people to picture themselves in someone else’s shoes and think across every kind of border.

While things are much better now in Algeria than during the 1990s, in many other countries, the terror spreads. Meanwhile, the resistance escalates too, and so our support for those on the frontlines must increase. We have to learn from the past so we better support those who today carry on the struggle against intolerance in Muslim majority contexts. One of the crucial ways to do that is to expose the political ideology of Islamism they battle (which is not the same thing as the Islam it misuses). When I asked Ourida Chouaki, whose brother Salah was also killed by the GIA twenty years ago, how she wanted him remembered today, that condemnation was exactly what she asked for.

Among the latest victims of the same jihadism that afflicted Algeria, the 217 kidnapped Nigerian schoolgirls who have spent nearly three months in captivity. They are the Amel Zenoune-Zouanis of today. Part of the point of telling sad stories like Amel’s is to help write happier endings in the present. So I hope people everywhere will continue to insist: “Bring back our Girls!”

In the face of crimes like those Nigerian kidnappings, the creativity and defiance of those who challenge fundamentalists remains inspiring. I was delighted by a recent tweet in response to the patently absurd dictate from the commander of ISIS to the effect that Muslims everywhere should, to quote South Park‘s Cartman, “respect my authoritay.” A Pakistani dissident simply tweeted his own twist on the words of playwright Shahid Nadeem, which I had also borrowed: “Your Fatwa Does Not Apply Here, bro.”

In keeping with that spirit, I end with an appeal on behalf of a stalwart Saudi activist whose story is still unfolding. Free Raif Badawi! His personal story, which is still unfolding, is at the heart of this very political struggle.

[ted id=2042]

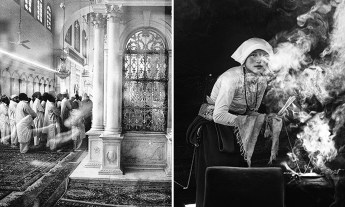

Featured image courtesy of El Watan.