After decades spent documenting faith communities around the world, photographer Monika Bulaj understands that our religions are more similar than we realize.

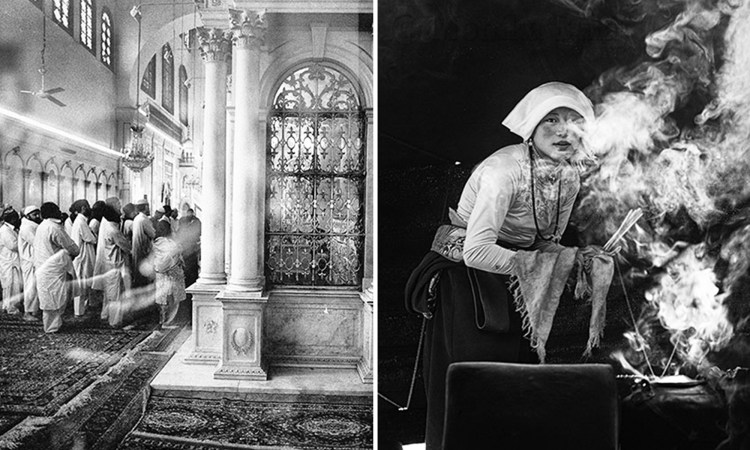

Polish photographer Monika Bulaj was sorting through her archive in early 2017 when she discovered an image she’d accidently exposed twice. Back in 2005, she had taken two photographs on the same negative: the first image was of Muslims praying at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus; the second, of Christians praying at a church in Aleppo.

By chance, those images she’d taken on top of each other had an almost mystic harmony. The Muslims crowding into the mosque on the right are balanced and framed by the open, praying hands of the Christians in Aleppo to the left.

“Now, in this time of the war, this double exposure was like a symbol,” Bulaj says of discovering the image while editing her new book, Where Gods Whisper. “But it’s nothing exceptional, because there are many places where people of many faiths pray together. So this photo is symbolic but not strange.”

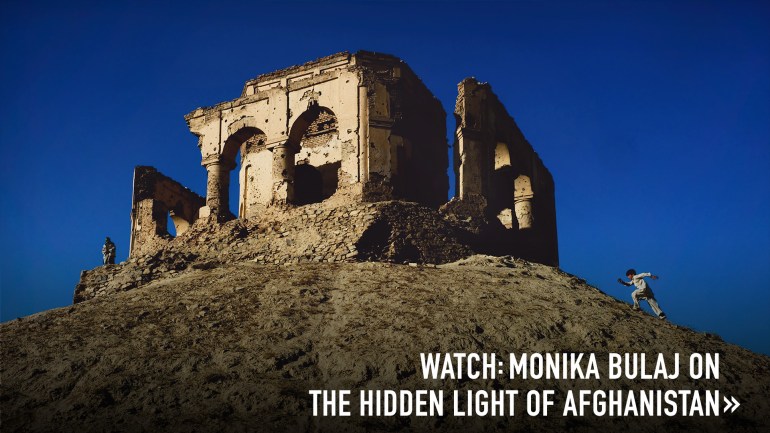

During her career, Bulaj, a TED Fellow based in Italy, has traveled the world documenting communities of faith while they perform their intimate, transcendent rituals. She has photographed Christians and Muslims in Syria; Hasids in Israel; Vodouists in Haiti; Buddhist monks in Tibet; and Sufi mystics in Afghanistan, Egypt, Libya, Iran and other countries.

“Wherever I travel, I meet the same human sensibility, just expressed in a different way,” Bulaj says. “I meet the same capacity of people to be open to each other.”

Bulaj grew up in Communist Poland and was raised as a Catholic, the primary religion there. From a very young age, she was drawn to the horrible tragedy of the Shoah of her home country. “In the case of my generation, which did not live through the war, it has become our duty to remember and to react to similar injustices when they happen today,” she says.

Bulaj began to travel through eastern Europe to document its ethnic and religious minority groups, including communities of Jews and Eastern Orthodox Christians. This work sparked in her a lifelong dedication to understanding and spotlighting religious groups, especially minority groups, around the world. “I feel an urgency to rush into areas where there is fragility, areas of war or conflict, in which something is about to disappear,” she says. “I visit all of these places with the crazy hope that they might not disappear.”

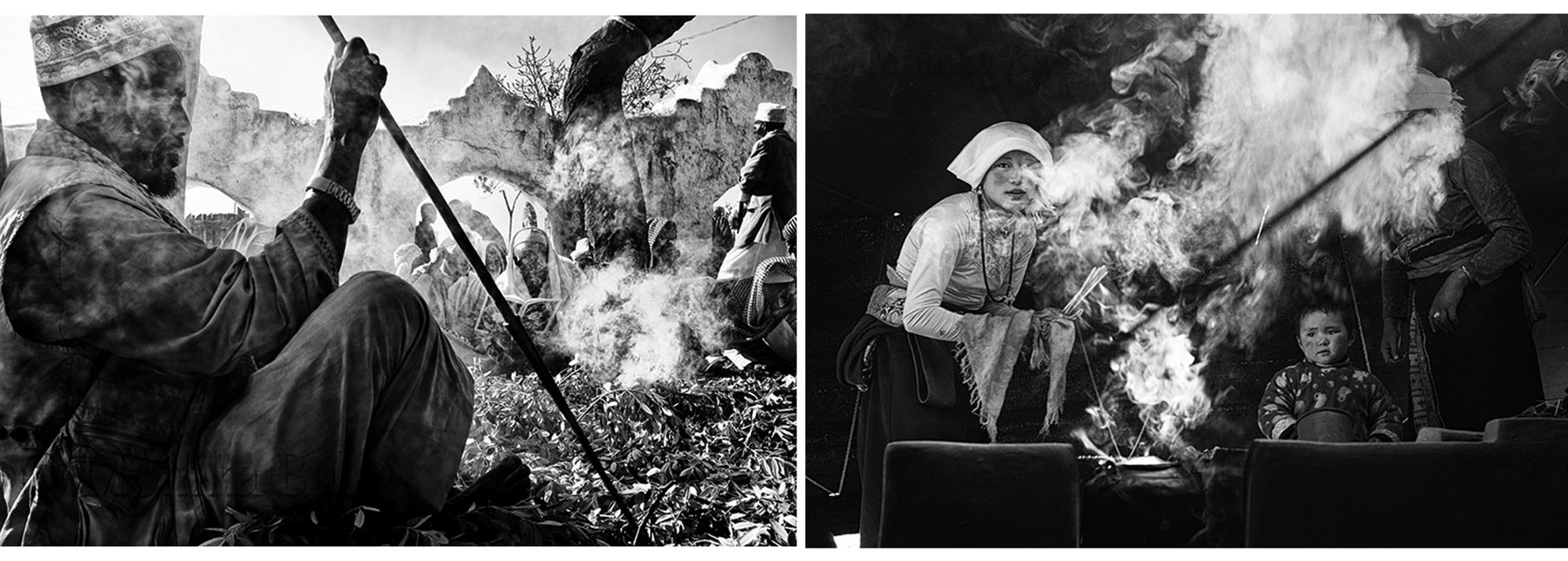

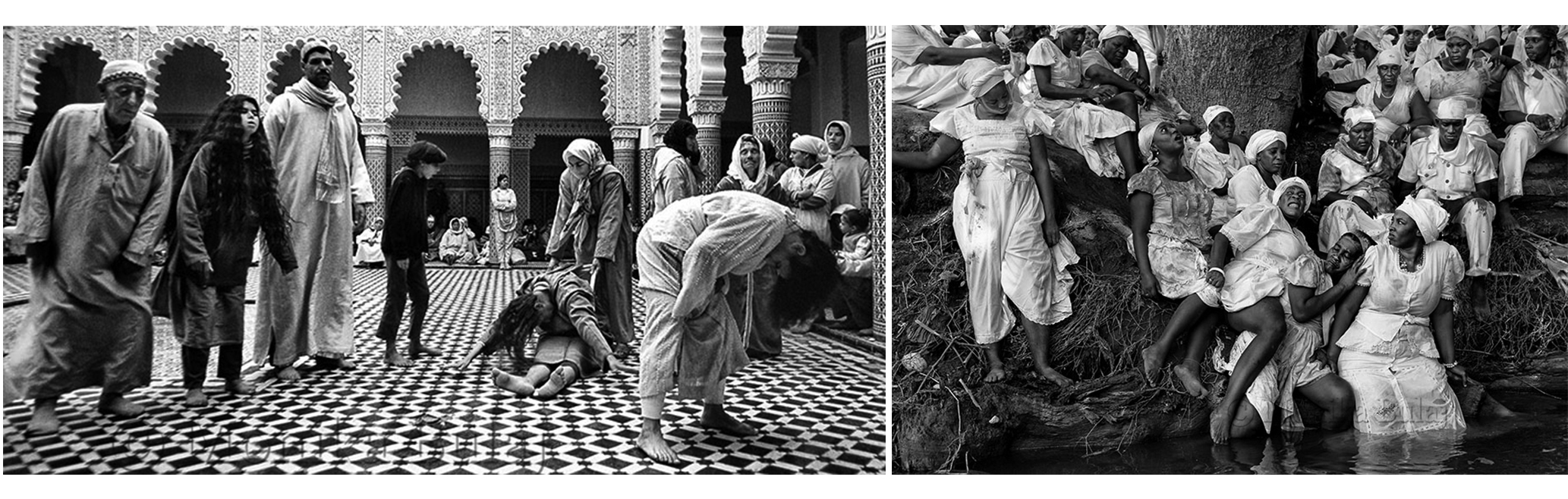

After decades of close observation of these communities, Bulaj has come to see more similarities than differences in our many expressions of faith. Again and again, she has observed the same fundamental themes: the power of faith to heal, to sublimate trauma, to honor the dead, to express the mystery and beauty of life.

“Religions have reflected one another for centuries. They’ve borrowed gestures, tunes, customs and saints from each other, just as good neighbors lend one another salt,” Bulaj says. “I like to explore the borderlines of monotheism. With my photographs, I’m very interested in bringing these practices of faith closer together. Of course, they’re not absolutely the same, because they are the fruit of centuries of evolution in a culture, something which is very beautiful.”

In her striking black-and-white photographs, Bulaj captures these overlapping themes across space and time, from the recurring shapes of the praying body and the facial expressions of ecstasy to the symmetrical structures of our places of worship, the central role of fire and water, music and dance, and the theatricality of the religious ritual.

“What interests me as a photographer and a writer is the question of how the body manifests this religious experience,” she adds. “The intensity of praying people is universal — their trembling, sensitivity, suffering, nostalgia, tears. But the resemblance is also something much more subtle. It is not just mimesis — the physical resemblance of facial expression, gestures, choreographies, liturgical clothes. It is something much more archetypal, which is difficult to express. Perhaps in photography there is a question of arriving at the threshold of this inexpressible, invisible thing.’”

Bulaj has worked in places that today are seen as incubators of religious fundamentalism across Africa, the Middle East and Asia. But instead of focusing on the fissures, her works pay special attention to places where diverse religious groups pray together as one — “the lands where people have communed for millennia, where the chains of vendettas snap, where people share food, friends, dreams and songs,” she says.

At the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, she has photographed Christians and Muslims, Shia and Sunni both, who’ve prayed together there for centuries; the Bosphorus, where Armenian and Turkish women settle down to sleep beside one another; and Deir Mar Musa, a monastery north of Damascus, Syria, which was restored by Christians and Muslims together. “I document faiths and traditions of the weakest and most defenseless,” she says. “But I also want to capture their capacity for dialogue and meeting.”

Bulaj likes to tell the story of the Italian Jesuit priest Paolo Dall’Oglio as an exemplar of such interfaith communion. Dall’Oglio has spent his life working at the Deir Mar Musa monastery, building bridges between Muslims and Christians. “He believes that the most important thing is to have dialogue with the enemy, with the people who think differently than you,” she says. “It’s very easy to speak to the people who have a sensitivity like yours, but it is very, very important to speak with people who are different.” In 2013, Dall’Oglio was captured by ISIS and his whereabouts are currently unknown, but his message of the possibility of interfaith dialogue endures. “The dialogue begins in the heart, when you walk on your brother’s land and learn from him about the springs he drinks from,” Bulaj remembers him telling her.

Bulaj points out that such dialogue is also essential to her own process as a photographer, writer and documentarian when gaining access to important places of worship and intimate religious ceremonies. “I love photography, but the photograph is not the most important thing. The most important is meeting people,” she says. “When I photograph, I move with people because they are moving. I walk with them on pilgrimage, and I sleep close to them. I eat with them. And, sometimes, when the people are dancing, I put my camera down, and I dance with them.”

Now that her new book, which sold out in English in just three months, is out, Bulaj will continue to explore these “sacred crossings” in every corner of the planet, with a special focus on Asia and Africa. “Of course, this book is not the end of this research,” she says. “This is only one stage, an episode in much longer research. Human stories are so much greater than any fantasy, but we must go slow, with time and with love, to collect them.”

All photos are from Monika Bulaj.