Helping prisoners get a legal education benefits them and the world, says African Prisons Project founder Alexander McLean: They can help their fellow inmates with their legal expertise, and when they’re released, they can help society, too.

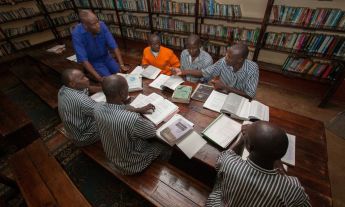

Seven young men sit around a table covered in textbooks. They are having an animated conversation in a room where bookshelves line the walls. It could be a study group meeting at any university library around the world. But these students are noticeably thin, with identically shaved heads and matching blue-and-white-striped shirts.

These law students are inmates in a Ugandan prison. They’re enrolled in a program that is teaching them to advocate for themselves and their fellow prisoners in their nation’s criminal justice system. The program is sponsored by the African Prisons Project (APP), a group founded in November 2007 by then-law student, now UK barrister, Alexander McLean (TED Institute Talk: Restoring hope and dignity to the justice system). A few years earlier as a teenager on a Christian mission to a Ugandan hospital, McLean had observed as overtaxed staff left mortally ill patients from a nearby prison to die. He wondered whether a criminal justice system could help the people it imprisoned rather than harm them.

“How do you use prisons as spaces where you take people who’ve been on the margins of society and equip them to come out and change their families, communities and nations?” he asks today. Now in its tenth year, APP continues to answer that question by sponsoring health, vocational and literacy training at 27 Ugandan and three Kenyan prisons that collectively house around 15,000 inmates. The programs teach staff as well as prisoners how to educate and care for their own communities inside and outside the prison. McLean, a TED Fellow, and his team hope that in the next several years APP will be able to dramatically expand its legal education program, from 63 current students to hundreds in Uganda, Kenya and other African countries.

At first, APP focused on improving conditions in Ugandan prisons in ways intended to affirm the prisoners’ humanity. “We refurbished and built libraries and clinics,” says McLean, “thinking that having quality infrastructure would bring prisoners dignity.” After a few years, however, he realized that with an inmate illiteracy rate of 67 percent and with a lack of trained medical personnel on prison staffs, those kinds of improvements weren’t enough. So APP began hiring professional educators to teach reading, basic medical care and job training in the prisons. It opened up classes to staff members, who were often as poor and undereducated as the inmates. “Prison staff and their families were deeply vulnerable, too,” McLean says. “We could create huge resentments by not thinking about their needs.”

Bringing in educators quickly became expensive, but a solution was right in front of them. “There were amazingly bright people in prisons: prisoners and prison staff who were already serving in different ways, whether leading the prison football team, or an inmate who had completed high school and was teaching his peers at the high-school level, or prison staff [coming] in on their day off to do Bible study, or an inmate being a leader in the prison mosque,” says McLean. In 2012, the project began training prisoners and prison staff as peer-to-peer adult literacy teachers, as well as in basic health and medical care.

Offering legal education was a logical next step. In the Ugandan and Kenyan justice systems, “80 or so percent of prisoners never meet a lawyer,” McLean says. In 2011, APP sponsored its first group of nine students to participate in an online legal studies program offered by the University of London.

“It’s cheaper to educate than to incarcerate,” says Baz Dreisinger. “If we don’t want to keep recycling people into and out of an expensive system, then education is key to reducing the recidivism rate.”

If a society’s goals include rehabilitating rather than punishing the incarcerated, then providing prisoners with different educational options is crucial. “Certainly in the US but also from what I’ve seen globally, most prisoners weren’t given adequate educational opportunities to begin with,” says John Jay College of Criminal Justice professor Baz Dreisinger, author of Incarceration Nations. “The most fundamental reason why a society needs to give education to people in prison is because it failed them in the first place.”

Offering higher ed and vocational training to prisoners has practical benefits. Education enables released convicts to succeed at re-entering society and avoid landing back in prison. “It’s a moral issue at heart, but it also makes sense economically,” says Dreisinger, “with numerous studies that show how it’s cheaper to educate than to incarcerate. If we don’t want to keep recycling people into and out of an expensive system, then education is key to reducing the recidivism rate.”

Prisoners have embraced APP’s legal education program. Since that first group of nine students — who were all prisoners at one maximum-security prison in Uganda — the program has grown to 63 students across all 30 prisons in Uganda and Kenya served by APP. Three students have completed an undergraduate law degree, or LLB, roughly equivalent to a J.D. degree from a US law school. Four students have completed a more basic course of study to earn law diplomas.

Legal program participants have gotten 3,000 prisoners out of jail via bail or dismissed cases; overturned sentences for 77 inmates; reversed seven death sentences; and freed four people from death row.

Even while they’re learning, students begin using their knowledge to help their peers. Legal program participants have provided 50,000 hours of legal counseling to 5,000 prisoners (a third of the combined prison populations), according to APP. Their accomplishments include getting 3,000 prisoners out of jail via bail or dismissed cases; overturning sentences for 77 inmates; reversing seven death sentences; and freeing four people from death row. These last include APP’s first female law student, Susan Kigula, who spent 16 years on death row in Uganda’s Luriza Women’s Prison before walking free in 2016, thanks in part to her own advocacy.

While in prison, Kigula initiated a constitutional challenge on behalf of herself and 416 fellow death row inmates. Her efforts resulted in a landmark achievement: the mandatory sentence for murder and armed robbery was overturned in Uganda. Kigula, who completed her University of London law diploma, “is now working with us, going back into women’s prisons,” says McLean, “and providing legal education and advice and support to others who are following in her footsteps.” Her accomplishments are just one example of how a legal education could change the lives of other prisoners in Uganda and Kenya.

Since starting its legal education program, APP has seen “amazing things happening,” says McLean. “We’ve seen our first graduate go from being a prisoner to being a lawyer in the Ugandan army. We’ve seen members from the outside community going into prisons to access legal services from prisoners.” And he has ambitious goals for the legal program. “Next year, we’re anticipating taking on another 45 to 50 new students,” he says, and by 2020, hopes to see a ten-fold increase in the number of prisoners released with assistance from an APP-sponsored legal professional, from 3,000 to 30,000.

To meet the enormous demand for legal counseling from its students, the APP team is trying to set up Legal Aid clinic-style services. By working at the prison grassroots, with inmates and staff, APP may be able to build a solid foundation for lasting change in addition to transforming individual lives, says University of Michigan history professor Heather Ann Thompson. “It’s about using prisoners to speak for themselves, reform their own institution, but also to become part of the society in a way that we would all benefit from,” says Thompson, who won a Pulitzer Prize for her book Blood in the Water:The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and its Legacy. “What’s the alternative? You warehouse people.”

McLean says, “Often, when people think about what happens to ex-prisoners and how to re-integrate them, it’s ‘How do we help them to use their hands?’ I think, ‘How do we let them use their brains? ’”

Lack of access to resources is a major challenge to expansion. Due to prison security needs, inmate access to the Internet — critical for legal education — is restricted. To compensate, APP hires part-time tutors to teach in the prisons, assist students in research and provide them with study materials. Many prisons also lack basic classroom facilities, in part due to overcrowding. “Often, classes are conducted in open environments or under a tree,” says Charles. “Occasionally students will be allowed to use administration offices as makeshift classrooms.”

By working at the prison grassroots level, APP is aiming to transform lives and even systems. McLean believes the project could influence practices in Western nations with troubled prison systems such as the UK and the US. “Our focus is on showing that our legal work can work on a national scale in an East African country, but we’re definitely thinking of future strategies of what it looks like to move beyond these borders,” he says. “Often, when people think about what happens to ex-prisoners and how to re-integrate them, it’s ‘How do we help them to use their hands?’ I think, ‘How do we let them use their brains? How do we take these people who’ve been in prison and allow them to give society what they have to offer with their bright, creative, passionate legal minds?’”