Dr. Samantha Nutt, an international humanitarian and author, writes about misogyny and the continuing struggle for women’s equality — and points to the way ahead

I didn’t think I’d feel this way again. Many years ago, a guy I was dating became upset with me after I outperformed him on a science final exam that was worth a large percentage of our GPA. “You already do better than me in every other course,” he huffed, explaining that he needed time away from “us” to get over his anguish, “but this was supposed to be my thing.”

There it was. I’d embarrassed and emasculated him. Unable to detect his alpha-dog scent, I’d crossed into territory he’d already psychically marked as his. I’d forgotten my place. This, to me, has been the unsettling message behind the 2016 US presidential campaign. There were the locker-room excuses and the dismissals of women’s complaints of unwanted sexual advances on the basis of their age, appearance and overall “score.” There was Donald Trump’s declaration, while shaking his head like an angry vice principal, that Hillary Clinton was “such a nasty woman” when she upstaged him during a debate. There were the “Lock her up!” rallying cries, the “Trump That Bitch” T-shirts — all part of a concerted effort to take Clinton down a peg or two. To take all women down a peg or two. He galvanized voters, in part, by convincing them that their failures could be blamed on others — minorities, women, liberals — robbing them of the things that were supposed to be their thing. Time to break up with them.

As women, we hear and experience versions of this far too often.

Domestic violence, sexual assault and harassment, and the daily diminishments that involve being talked over, dismissed, obsessively scrutinized or simply ignored — these are some of the ways in which women are admonished, at times killed, for not minding their so-called place. It’s a universal problem. It was rampaging through Cairo’s Tahrir Square during the Egyptian uprisings, when women protesters and journalists were groped, beaten and raped. It was explicit in the explanations proffered by the young men who gang-raped to death Jyoti Singh, a 23-year- old physiotherapy student, for getting on a New Delhi bus late at night in 2012. “A girl is far more responsible for rape than a boy,” declared one attacker. “Housework and housekeeping is for girls, not roaming in discos and bars at night doing wrong things, wearing wrong clothes.”

It’s also present in the barrage of criticism heaped on any woman who has ever published anything remotely political or opinionated — criticism that is undeniably designed to degrade us, which it does, and to silence us, which it also does. The creator of the hashtag #yesallwomen, for example, was subjected to such appalling online abuse that shortly after sparking a long-overdue global conversation she found herself curled up at home where, she wrote, she “waited to die.” Men in the public eye experience criticism too, but it’s rarely couched in crude requests for sexual favors or insults about their likeability. Women, especially those with any degree of public profile, must always be seen as friendly, approachable, relatable and bed-able, and young girls receive this message every day. Whereas men can be those things, or they can be total assholes, or anything else they want to be — theirs is a menu of choices.

A growing body of evidence shows that women in leadership roles — especially women leaders who are overtly ambitious — tend to be seen as threatening by men, prompting those men to act more assertively towards them. This may be one of the reasons why women can’t move as easily up the corporate ladder, or achieve closer to equal representation in politics: The more we strive to do, the more we are resented, and the more we are resented, the greater the barriers to advancement.

Of course, the struggle goes far beyond the realms of politics and business. Having worked in the humanitarian sector for more than two decades, I’ve seen what happens when this kind of hatred toward women is weaponized.

I recently returned from Iraq where I was working for War Child, an international charity that helps women and children rebuild their lives in the aftermath of violent conflict. There, girls and women are fleeing a brutal, genocidal regime which for the past two years has created an efficiently misogynistic system to control, degrade and ensure they do not enjoy the same privileges as men. I met girls who had been taken from their families at ages 12 and 14, given as bounty to ISIS leaders or sold as chattel in markets, and raped and abused repeatedly. Even after they escape these nightmares, they invariably confront a new one: abuse at the hands of people in their own communities, who perceive them to be tainted, damaged goods. They are girls with simply no place at all.

I wish I could say that I had responded to Mr. Bruised Ego in my university days with the force of 1,000 suffragettes. I did not. I did what legions of women have done out of people-pleasing paranoia and what Clinton did in her concession speech: I apologized. I reassured him that he was better than me at that subject. If I could grab that young woman today, I would hoist her up by her un-ironic overalls and tell her: “You’re not the problem; he is.”

If we can take anything away from the past few months, it’s that the struggle for women’s equality must continue. We still have a long way to go.

Some people have argued that Clinton was never the “feminist” candidate. They denounced her as being too establishment and not enough change. But the toxic narrative about women that emerged from this election — and that is more painfully evident in the corners of the world I frequently work in — is more proof than we could ever want that the women’s movement is unfinished everywhere.

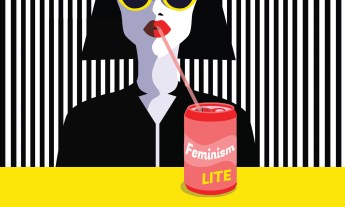

Our mothers and grandmothers took bold, defiant steps to confront the underlying prejudices and assumptions that denied women the right to pursue full and equal lives. This work is far from over. Feminism, as the last few months have shown, is a process — not a history lesson. But there is one certain way forward: Find young women, wherever they are in the world, and get behind them. Volunteer for their political campaigns, even at the municipal level, because it’s a long path to the White House. Reach across the oceans by supporting humanitarian agencies that make it possible for women and girls living with war and violence to find help and opportunity, instead of fear. And remain undaunted, every day, in the face of those who seek to deny us that chance. Our place, as women, is every place.