There’s a kind of Hunger Games occurring among organizations and brands to seize people’s attention and loyalty. Here’s what it takes to win power in today’s hyperconnected age, according to activists Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms.

Today, we have the capacity to make movies, friends or money; to spread hope or spread our ideas; to build community or build up movements; and to spread misinformation or propagate violence on a vastly greater scale and with greater potential impact than we did even a few years ago. Yes, this is because technology has changed. But the deep truth is that our behaviors and expectations are changing too.

Think of the hoodie-clad barons who sit atop online networks a billion users strong. The rank political outsiders who have raised passionate crowds and swept into office. The everyday people, businesses and organizations who are leaping ahead in a hyperconnected world — while others fall back.

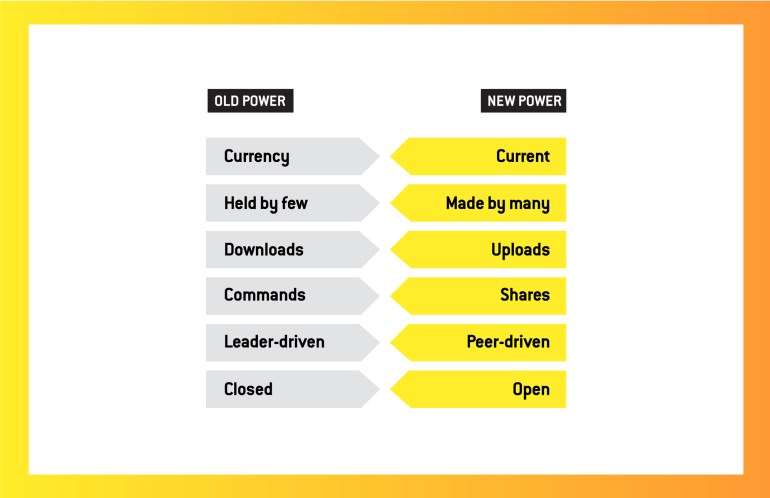

Our world is defined by the battle and balancing of two big forces. We call them old power and new power. Old power works like a currency. It is held by a few. Once gained, it is jealously guarded, and the powerful have a substantial store of it to spend. It is closed, inaccessible and leader-driven. New power operates like a current. It is made by many. It is open, participatory and peer-driven. Like water or electricity, it’s more forceful when it surges. The goal with new power is not to hoard it but to channel it.

For any new power movement, identifying and cultivating the right connected connectors is often the difference between takeoff and fizzle.

Having a connected and passionate crowd on your side has become a crucial asset in gaining new power. Today, the tools and tactics available to movement builders have expanded hugely. At the same time, it has become harder to break through because everyone is trying to rally a crowd. Whether you’re working to get elected to your local school board, launch an online community, or trying to build buzz around your new business, these are the four key steps to starting and growing a flourishing movement today.

Step 1: Find your connected connectors.

For any new power movement, identifying and cultivating the right connected connectors is often the difference between takeoff and fizzle. Etsy, the online crafting marketplace, now has tens of millions of members and generates hundreds of millions of dollars each year. Yet it only got off the ground thanks to small groups of digitally savvy feminist crafters.

The building blocks of a new power brand are very different from those of a purely commercial or transactional brand, or a top-down organizational one.

The platform was founded in Brooklyn in 2005 by four men, including Rob Kalin, a maker who wanted a market to sell his crafty, wood-covered computers. He wasn’t alone. In the early 2000s, there was a resurgence of enthusiasm for DIY artisanship. The early Etsy team deliberately recruited the most influential crafters at flea markets and promised them a place to sell their wares online. Critically, it also provided moderated forums on its website that allowed these crafters — who already shared a worldview and had mutual offline connections — to find one another. This blog post from early 2008, cited in Morgan Brown’s account of Etsy’s rise, sums up the company’s efforts to appeal to its community:

Etsy’s core mission is to help artists and crafters make a living from what they make. This may seem like an innocuous enough statement, but truth be told, the socio-political-cultural-economic state in which we live makes this a rather bold rallying cry. We want to make history’s “way of doing things” undergo a change . . . Etsy is part of a larger movement, and we at Etsy want to learn more about the consciousness of feminist crafters in our midst.

Etsy had found its connected connectors, who fueled the company’s growth organically; new power was its sales and marketing engine.

Step 2: Build a new power brand.

Every company or institution must make key early decisions about how it will project outward into the world. It has to come up with a name and settle on a visual aesthetic; it needs to refine a voice for how it speaks to consumers or clients. These things define its brand. The building blocks of a new power brand are very different from those of a purely commercial or transactional brand, or a top-down organizational one.

When Airbnb emerged in 2008, founders Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia and Nathan Blecharczyk just wanted to find a way to pay the rent on their San Francisco apartment. But as the company grew, it did so less like a franchise, with every room looking the same, and more like a movement, with early users sharing a passion for a new kind of stay — one that provided instant community in a new place, a host to guide them in a new city.

By 2014, Airbnb had in many ways moved beyond its earlier, more intimate and homemade feel. But its founders needed to maintain that critical point of difference from checking in and out of a Best Western; losing the communal and community spirit of their early days was a real business threat. And there was another threat, too: the regulatory challenges to Airbnb that were popping up all over the world. It had begun to rally its hosts as a way of fighting back against city governments, which made users’ bond with the platform even more critical.

In a world awash with competing opportunities, achieving frictionlessness has become necessary for anyone trying to build a crowd.

So Airbnb relaunched its brand, with a brand story made for the age of new power. Its new logo was not designed to be admired but to be remixed and adapted by different affinity groups within the Airbnb community. Airbnb even introduced a tool, called Create, to make it easier to remix the logo. “Most brands would send you a cease-and-desist letter if you tried to re-create their brand,” said Airbnb’s CEO Brian Chesky at the time. “We wanted to do the opposite.” The Create tool signaled the way Airbnb saw its community — as a place where you could both belong and be yourself.

Airbnb also retooled its corporate language with a manifesto more like that of an alternative-living community than a Silicon Valley money machine:

We used to take belonging for granted. Cities used to be villages. Everyone knew each other, and everyone knew they had a place to call home. But after the mechanization and Industrial Revolution of the last century, those feelings of trust and belonging were displaced by mass-produced and impersonal travel experiences. We also stopped trusting each other . . . That’s why Airbnb is returning us to a place where everyone can feel they belong.

Airbnb’s brand voice is built to cultivate a sense of community and participation, and executives are betting that this will be a key source of competitive advantage. It spends millions holding an annual gathering of thousands of its most active hosts, building solidarity and esprit de corps. Going further, it has invested in supporting local groups of hosts as part of a decentralized home-sharing club, supported by Airbnb but led by its most involved members.

Step 3: Lower the barrier, flatten the path.

A macro theme of our age is that participating in almost anything has become easier, whether we are protesting, taking vacations or managing our dating lives. In a world awash with competing opportunities, achieving frictionlessness has become necessary for anyone trying to build a crowd.

An unlikely digital wunderkind has used the same logic to produce an enormous surge of new power. Indian anti-corruption activist Kisan “Anna” Baburao Hazare is eighty. For decades he has campaigned for social justice in the Gandhian tradition — nonviolent protest driven by acts of personal sacrifice, such as “fasts unto death” to protest corrupt officials and unjust laws.

In 2011, Hazare was staging his biggest campaign yet: in support of what became known as the Jan Lokpal legislation, a national bill that would strengthen the power of ombudsmen to hold public officials accountable at all levels. In early April of that year, after the prime minister rejected his demands, Hazare announced he was beginning a fast until the bill was passed. Hunger strikes are a very powerful tactic, especially given their legacy in India. But there’s a weakness: they don’t give other people anything to do except express support (at least not unless you’re willing to do the same).

Hazare began to experiment with new tactics. He asked Indians to send him an SMS if they supported his campaign. Among the emerging middle class who formed the backbone of his supporter base, mobile penetration was near universal. So he got himself a shortcode and generated about 80,000 texts from ordinary Indians, a respectable effort.

The most effective crowdbuilders will be those able to move people up the participation scale and sustain and nourish a community over the longer term.

Then Hazare subtly changed his tactics. All over India and in many other parts of the developing world, people use missed calls to communicate — you dial and quickly hang up, so your number pops up on their phone. If you’re running late for a coffee with a friend, you leave them a missed call. If you’re dating someone and just want to let them know you’re thinking about them, you leave a missed call. Unlike phoning or texting someone, leaving a missed call is free. It’s also effortless.

This small change made a spectacular difference. When Hazare provided a local number to call and asked Indians to show their support for his campaign, his numbers went from 80,000 to 35 million. Thirty-five million missed calls. That’s one of the largest single coordinated acts of protest in human history. It’s a great example of how to build a crowd in a new power way, and central to it was using an existing behavior (the missed call) that made the barrier to participation low. Taking part was truly frictionless.

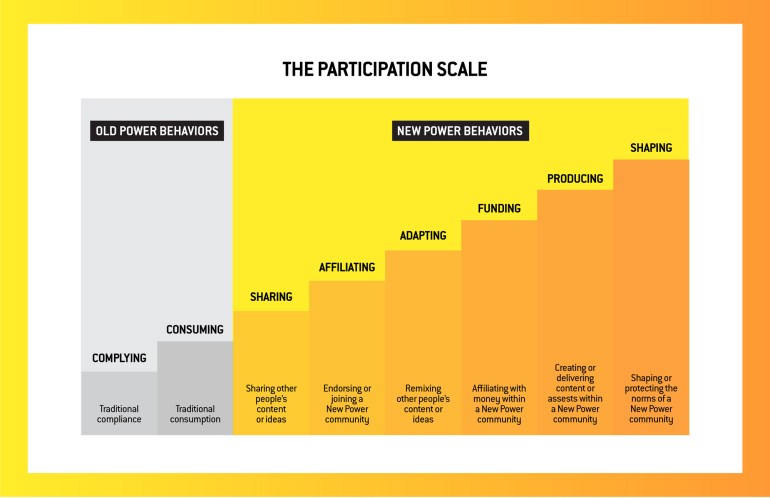

Step 4: Move people up the participation scale.

You might ask, so what? What do 35 million calls really add up to? Isn’t this just clicktivism? Hazare turned those phone numbers into real, on-the-ground power. Two weeks after this call to action, his campaign had the world’s largest spreadsheet of phone numbers of supporters. People on the list were contacted to help turn out hundreds of thousands of participants to real-world protests in Delhi and other cities. And while Hazare’s bill didn’t pass as is, the government accepted some demands, and his campaign helped push through sweeping changes to laws against corruption.

When you’re trying to build a movement or grow a crowd, you get people in the door via simple, low-barrier asks. Once you have recruited these new participants, the job is to keep them engaged and to move them up the scale, toward higher-barrier behaviors like adapting or remixing the content of others, crowdfunding a project, creating and uploading their own unique content or assets, or, at the top of the scale, by helping to shape the community as a whole. Think here of the Airbnb super-hosts who set norms for others on the platform, the significant but informal role played by the Black Lives Matter founders, or the most influential volunteer moderators on Reddit.

The public realm is becoming a kind of Hunger Games for organizations and brands. The most effective crowdbuilders will be those who are able to move people up the participation scale and sustain and nourish a community over the longer term, dealing with the many challenges, compromises and balancing acts that requires.

Excerpted with permission from the new book New Power: How Movements Build, Businesses Thrive, and Ideas Catch Fire in Our Hyperconnected World by Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms. Published by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2018 by Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms.