Last Mile Health has expanded health-care access to the most remote regions of Liberia. Raj Panjabi, the nonprofit’s founder and winner of the 2017 TED Prize, looks back at how his team handled the Ebola outbreak — and how it can help them build a healthier future for their country and us all.

In December 2013, a 2-year-old boy named Emile died of Ebola in southern Guinea. He was Ebola’s patient zero, and the disease went on to claim more than 11,000 lives, predominantly in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, but with effects felt worldwide. I watched the Ebola crisis unfold from a unique vantage point. I was born in Liberia and fled to the United States in 1990 during my country’s civil war. After attending medical school in America, I returned to Liberia in 2005 to serve as a physician in rural areas.

Through Last Mile Health, the nonprofit I founded in 2007, I’ve made it my mission to train community health workers — people living in remote areas who are given the medical know-how to treat their neighbors. So when I first heard about the Ebola virus in March 2014, I was concerned. Liberia shares a border with Guinea and, to its credit, Liberia’s Ministry of Health acted swiftly, getting staff in place to track the disease and deploying resources to respond. By May 2014, we had made it through 21 days without another case arising. That’s the incubation period for the disease, and we waited anxiously. If we could go another 21 days without a new case, we could declare the country disease-free.

Unfortunately, days later, Ebola erupted in the capital city of Monrovia. This was the first time the disease had appeared in an urban center, and from there, the number of cases rapidly multiplied. We knew we were looking at an unprecedented epidemic. Last Mile Health and several partners were asked to help the government create a plan to combat it.

Below are four hard truths revealed by the epidemic — and why we need community health workers to stop future outbreaks.

1. Blind spots in rural health care can become hotspots of disease

When I first returned to Liberia, the country’s health-care system had been decimated by war — there were 51 doctors to serve nearly 4 million people. Imagine if Washington, DC, had only eight doctors available to cover all its residents. What’s more, the 51 doctors were mostly located in cities. This matters because 75 percent of today’s emerging infectious diseases first enter human populations from animals, or have what’s called a zoonotic origin. Ebola and other zoonotic diseases, like Zika (which originated in Uganda’s Zika forest) and HIV/AIDS (which originated in Central Africa’s forests), often begin in the world’s most remote regions, areas that also tend to have limited health care. Rural communities in West Africa and around the world face a “triple bias” in obtaining medical services: the public sector considers them a low priority; the private sector doesn’t see profit potential in these sparsely populated places; and even NGOs consider it too expensive to serve them.

But these blind spots in rural health care put us all at risk. After two-year old Emile died, the virus quickly killed dozens of people in surrounding villages due to the lack of well-supported, well-trained health workers. At a time when every minute counted, we lost months. The disease rapidly spread to the cities, and West Africa and the world eventually lost thousands of lives and billions of dollars. Ebola showed us that the cost of inaction in rural areas is far greater than the cost of action.

2. Before fighting an epidemic, despair must first be overcome

By September 2014, Liberia’s health-care system was paralyzed by fear. Nearly 3,000 people had died from Ebola, and new outbreaks were constantly reported. Experts warned that as many as 1.4 million people in Liberia and Sierra Leone might be infected within months, and most would die from the virus. Even during our civil war, we’d never heard projections this horrific. Hospitals and clinics were closing their doors out of panic.

This fear was very real. Ebola easily spreads from patients to providers if medical personnel do not have the proper protective gear. Hundreds of health-care providers — nurses, physicians and community health workers, including some of our mentors, partners, teachers and friends — had already died trying to treat the disease. The Minister of Health lost her secretary, and she was forced to go into quarantine herself.

There was a moment when Last Mile Health considered suspending its operations, because we feared putting staff in harm’s way. But in the midst of the chaos, Lorenzo Dorr, a Liberian health worker on our team, said, “We cannot despair in the face of crisis. Despair doesn’t solve the crisis; that takes leaders with solutions and servants who take action.” This was a defining moment, and his words became a mantra for us.

3. Far-reaching epidemics like Ebola can’t be stopped without community health workers

In October 2014, I stood in a mud-walled building in a remote rainforest community in Rivercess County. Lorenzo, our team and our partners were there to train a group of health workers. An outbreak had erupted in a nearby village called Kayah — an infected woman had walked ten hours to get help and died. Due to the isolated location, it took two weeks for residents to get word to authorities. In that time, more than a dozen people who’d attended the woman’s funeral had passed away from the virus and transmitted it to others.

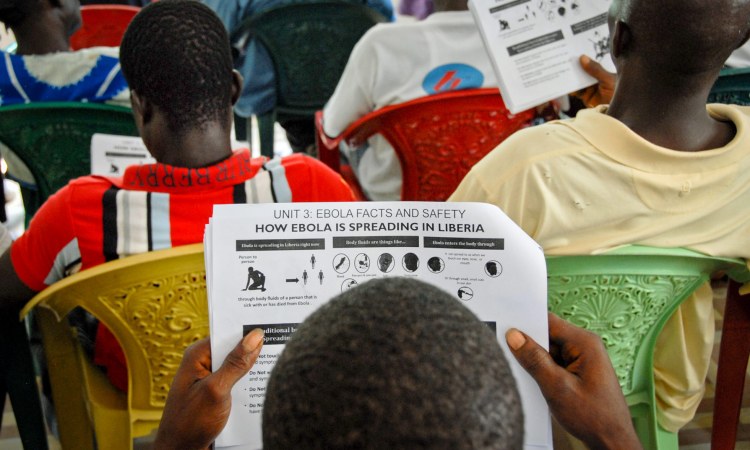

To contain the disease, three things needed to be done: we had to set up treatment units and get sick people into care as quickly as possible; we had to find everyone who was exposed to the virus and go door-to-door to collect blood samples; and we had to educate people on how the virus is spread from person to person. Last Mile Health developed a curriculum to train health workers in Rivercess County and adjacent Grand Gedeh County, and our curriculum went on to inform the national approach. Working with the government of Liberia, we trained, equipped and supported 1,300 rural community health workers and nurses to supervise them.

Ebola couldn’t have been stopped without these workers. They included lab technicians like David Sumo, a 24-year-old who drove his motorbike more than six hours through mud in the rainforest to test hundreds of people at risk. Nurses like Alice Johnson distributed digital thermometers, masks, gloves and gowns to clinics. Community health workers like Zarkpa Yeoh set up chlorinated water stations for villagers to use since 87 percent of the communities we served had no running water. They also showed people safe burial practices and then they stayed on hand to make sure these rules were followed.

Determined rural health workers put their lives on the line for their fellow Liberians, and more than 500 died in the process. At the end of 2014, TIME magazine named “The Ebola Fighters” — health workers like Lorenzo, David, Zarkpa and Alice — as its Person of the Year, “for tireless acts of courage and mercy, for risking, for persisting, for sacrificing and saving.” They were the ones who helped stop the virus in its tracks. Finally, in March 2016, the World Health Organization declared Ebola was no longer an international public health emergency.

4. The best response to a crisis is a strong everyday health-care system

Every day, community health workers in Liberia still face the long shadow cast by Ebola. Its impact wasn’t limited to the people who died or were infected; its effects rippled throughout our health-care system. Patients stopped going to clinics because they feared contracting Ebola there. In particular, pregnant women became too afraid to see health-care providers, so we’ve seen a dramatic increase in women giving birth in unsafe conditions to the detriment of both mother and child.

It didn’t have to happen this way. Districts that made investments in well trained, well equipped, nurse-supervised, paid community health workers prior to the Ebola epidemic were able to continue their services and convince people not to shy away. In Konobo District, community workers ensured that no child with malaria or other illnesses missed a day of treatment even as the country’s health system collapsed. They also persuaded expectant mothers to keep coming to clinics for prenatal care and for childbirth.

Ebola has shown us that what works best in an emergency is not an emergency system — it is a robust and resilient everyday health-care system that reaches all people before threats emerge. To build such a system, Liberia’s Ministry of Health launched the National Community Health Assistant Program in July. This program, if fully financed, will employ more than 4,000 community health workers by 2021, as well as educate hundreds of nurses across Liberia to support them. This health-care workforce will serve as a frontline defense against the next local outbreak and prevent it from becoming a global epidemic. At the same time, the program will create thousands of jobs for people in rural areas, where the unemployment rate is 85 percent. Paying rural health workers is not a cost — it’s an investment. According to a recent report, every $1 invested in this way brings $10 in economic return. In Liberia and all over the world, people in rural areas often don’t have the opportunities to make a contribution and employing community health workers will be an effective way to develop their talents while maintaining the health of a community.

My colleagues and I have learned a great deal from our frightening, frustrating battle against Ebola. Everyone who took part in the fight has shown that we are not defined by the crises in our lives — instead, we are defined by how we respond to these crises. One of the best responses is to take our hard-won knowledge and use it to construct a healthier future for all.