Execution. A word that gives me the willies not because I picture a Westerosi royal beheader coming for my neck, but because it conjures images of budgets and bottom lines. Seriously, why can’t I just think for a living? When you live in a world of ideas, turning passion into a product is no easy feat, and it’s admirable when anyone has the guts to get out of the armchair and into Excel. But nonetheless act we must — and so it goes for TED speaker Thomas Goetz, who left Wired in January 2013 after 12 years to start his own company, and who in early 2014 launched his first product.

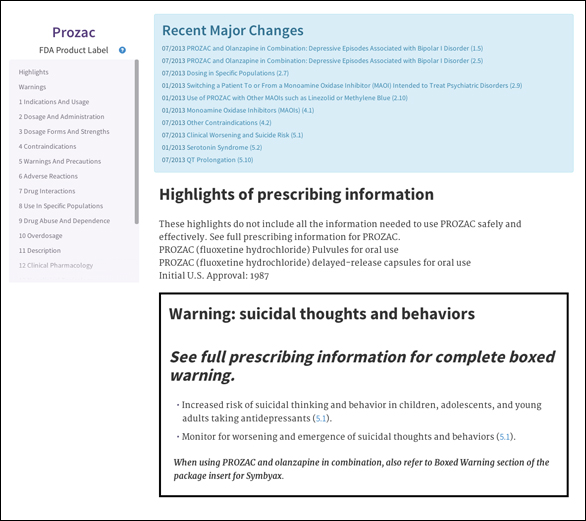

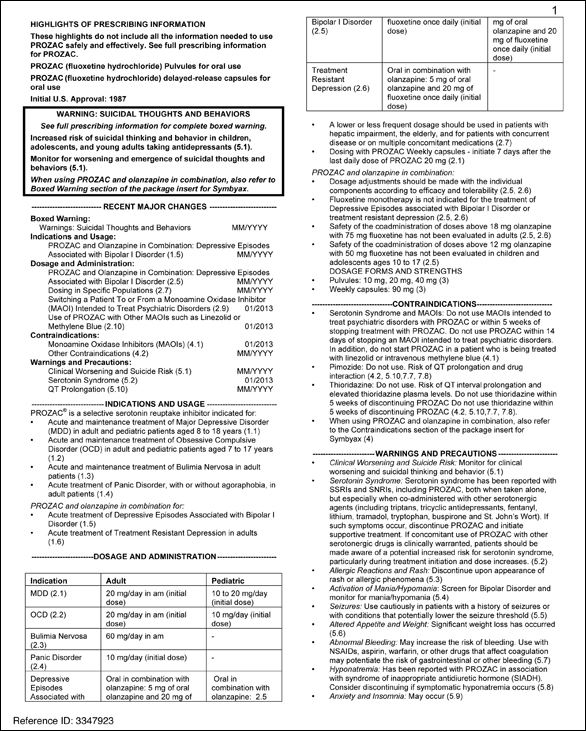

In his TEDMED talk, Goetz — who has a masters in public health and wrote the book The Decision Tree: Taking Control of Your Health in the Era of Personalized Medicine — spoke about what to do in the face of an endless labyrinth of medical data: Design better. In his talk Goetz shows a fake pharmaceutical ad and its accompanying FDA information. It’s indecipherable. Goetz points to the eye-glaze-inducing data, frustrated: “This is one of the most cynical exercises in medicine. … This is a bankrupt effort at communicating health information.” Goetz shows how Wired asked three designers to make over unintelligible lab results. Presto: The lab work makes sense. An important aspect of his vision, Goetz explains in his talk, was not only to visually transform medical data – a challenge on its own – but to help patients actually act on this information.

Goetz was Wired‘s executive editor, a words and ideas guy. But after his talk went live on TED.com – what Goetz calls a signal moment — the requests started pouring in. Could he make this idea a reality? As he tells TED over the phone: “There were hospitals, insurers, lab testing companies that all wanted to basically start using this. At first, I had to explain that this was a vision — this was the design of the idea, but it wasn’t a fully functioning product.”

But he realized it could be — and it should be. Other groups are working on medical data visualizations, but for Goetz, these beautiful visualizations didn’t empower people to act on the data. “Driving [people] to an action was the real thrust of what I was presenting in that talk,” he said. “I realized that it wasn’t going to be enough to observe and hope that somebody came along and did it right. That if I really wanted to do this, I would need to make a full and honest effort to try to make it happen.”

And so with former Google software developer Matt Mohebbi, Goetz launched his company, Iodine.com, in March. The goal: To bring better designed data to the people who really need it — that is, patients. Iodine taps a massive user demand for information about drug costs, effectiveness, side effects and interactions in a digestible but accurate way. Goetz calls it “data into design into decisions.”

In mid-December 2013 launched its first project: Med Labels, which are redesigned FDA drug labels. Search for any FDA-approved drug in the Med Labels database, and you’ll see all the information submitted by drug companies to the FDA in an easy-to-read format, indexed with links for jumping to relevant information. At the top of each page is a big bold button that lets you sign up for email notifications for any major changes the FDA issues to the drug label information. As a comparison, to find information on overdosing on Prozac from the FDA.org homepage, it takes seven clicks and a bit of hunting to find the page with the most recent label information, and — from there — a search on the page for the word “overdose.” (It’s not until the 6th instance that you arrive in the right place.) But in Iodine’s Med Labels database, you search “Prozac” to find the label page, then click on “Overdosage” in the left nav. And you’re there. Check out Iodine’s labels, versus the FDA originals, at the bottom of this post.

(Note: The National Library of Medicine provides a similar service, but the interface looks like it hasn’t been updated since the site was launched in 1993.)

It’s still early days for Iodine. But eventually it will help users make decisions like: Am I having a normal reaction to this drug, or should I go see my doctor? The goal is to allow users to input their age and gender and, based on similar people in clinical trials, determine whether their experience with a drug is typical. Medical data thus far, says Goetz, has been “designed for the doctor or the insurance company or whoever is footing the bill. Our health care system is structured [so] that consumers do not usually bear the brunt of the cost — so they are not seen as the customer.” It’s time for that to change, he says.

Iodine will put medical data in its users hands – which some critics call dangerous. Consider the discussion around 23andme, which until early December 2013 allowed people to send in their saliva for a genome sequencing and health-related feedback. Since late November, when the FDA delivered a public flogging over the accuracy of the service and ordered the company to stop marketing it, 23andme has become emblematic of the fight over patients’ rights. Still, Goetz only has admiration for 23andme as a way for people to actively engage with their health. “There are arguments that ordinary people can’t handle medical information … that the doctor should be the only vehicle for presenting medical information to an individual,” he says. “That is a classic paternalistic argument that has served medicine well for decades, but it is rapidly eroding as a plausible principle, in part because we’re putting much more onus on individuals. We’re expecting much more of individuals in terms of their responsibility for their health. But if we’re going to give them the responsibility, we need to give them the tools to manage it.”

According to Goetz, Iodine is meant not to supplant doctors but to supplement them. All of the information provided by Iodine is from clinical trials, and the company has a doctor and pharmacist on staff.

The important thing, says Goetz, is to realize that the end user in healthcare is really the patient.

Featured image via iStock.