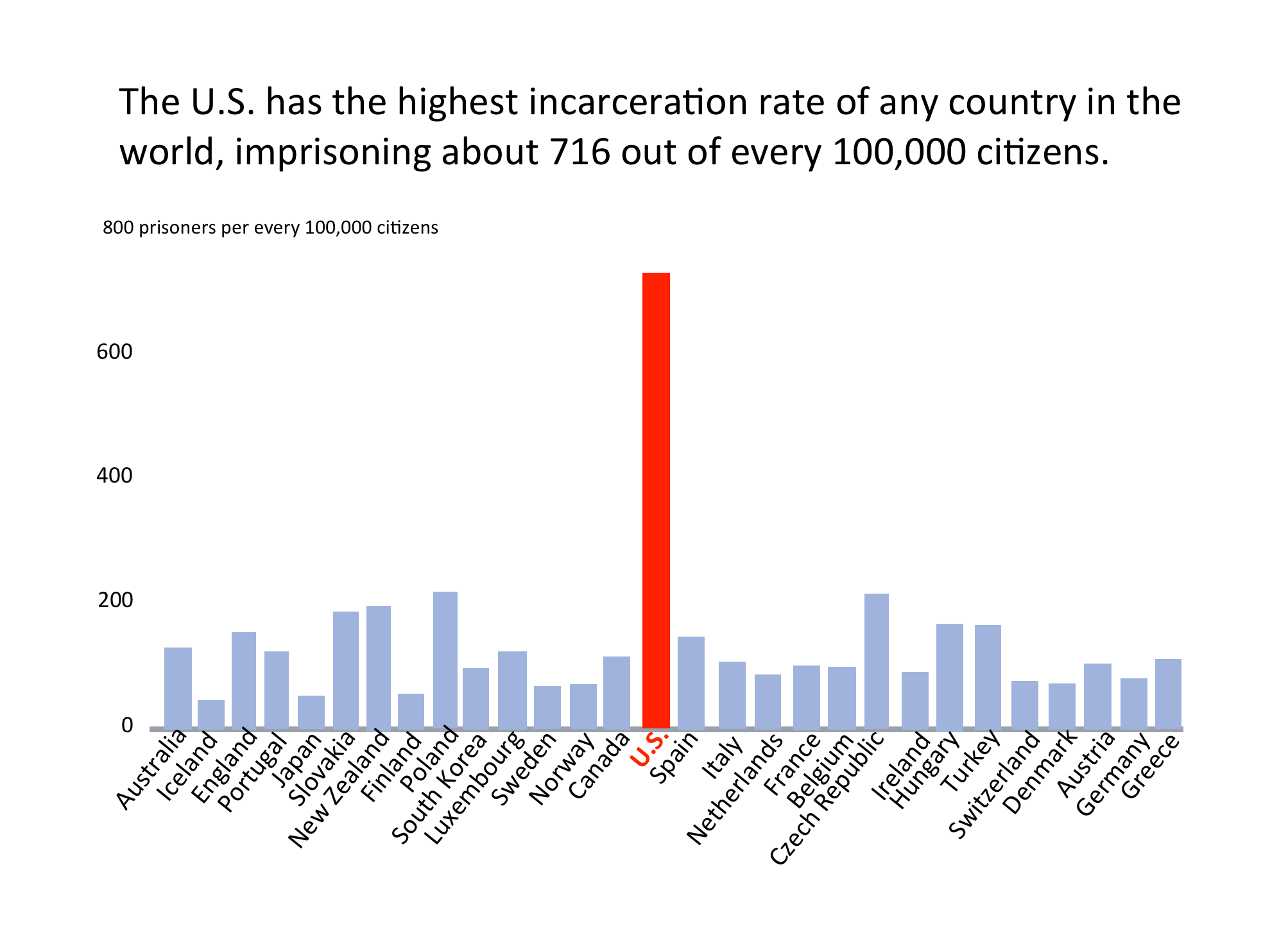

“We’re in this exciting moment where we’ve had 40 years of being ‘tough on crime,’ and we’ve finally come to recognize that it really hasn’t worked very well,” says sociologist Alice Goffman bluntly. “Scientists have shown in the past few years that the relationship between incarceration and crime is basically zip. The crime rate goes up and down, incarceration just continues to grow. It’s not a good way of fighting crime.”

When it comes to talking about jail, Goffman, a teeny tiny wisp of a woman with wide eyes and an open smile, does not mince her words. Sitting forward on a sofa in the Vancouver Convention Center, the day before she is due to give a TED Talk on the problem of using incarceration as a one-size-fits-all solution to crime, she is hopped up at what she sees as the injustice of it all. And she has seen it. As an ethnographer, she lived and breathed with the people in one particular neighborhood of Philadelphia for over a decade, young black men and their families who cannot escape a snakes-and-ladder system that seems like it has been designed to present them with one snake after another.

“Incarceration is targeted at poor African-American and Latino communities,” she says. “So what you have is not just young people going to prison and returning home, but people dealing with court fees, dealing with probation regulations, dealing with parole, living in halfway houses, on house arrest, going to court date after court date. It’s a very corrosive system that’s way bigger than just locking people up and returning them home with criminal records. It creates this culture of fear and suspicion where young people are looking over their shoulder, wondering when the police are going to come, wondering where they’re going to be seized or who around them is helping the police.”

Young people like Tim, who was placed on probation because his brother, Chuck, drove him to school in a car that it transpired had been stolen in California. Tim was charged with being “accessory to receiving stolen property” and placed on three years of probation. He was eleven years old. “And this is the point where Chuck starts teaching him how to run from the police,” says Goffman.

We urgently need to reconsider the disconnect between state and citizen, Goffman says — and tackling the wholesale incarceration of so many young people is a good place to start. Good news: the so-called “decarceration” movement is underway. “We’re starting to get out of the incarceration business, partly because it’s too expensive, and partly because we’re starting to see it as the civil rights issue of the day,” says Goffman. “We need to find new solutions to the violence that is plaguing poor communities,” she says. “That kind of violence comes out of economic and social exclusion, from severe deprivation, from when a whole society doesn’t believe in you. That’s what we need to change, not arresting and incarcerating young people.”