Multiple hurricanes. Multiple wildfires. A deadly explosion. And a pandemic that won’t quit.

2020 has been filled with crisis after crisis, with one relentless constant in their wake – hunger. And on the scene of as many crises as they can reach have been team members from World Central Kitchen (WCK), a nonprofit founded by Spanish chef José Andrés that provides meals to those in need.

The WCK mission is simple: To feed people after disaster strikes. In 2010, Andrés went to Haiti to serve meals after the catastrophic earthquake. Inspired by the experience, he founded World Central Kitchen. Since then, WCK has deployed relief teams around the world to sustain and nourish people when the worst happens. Despite their wealth of experience, 2020 has been a challenge … even for WCK. “It’s been the biggest, busiest year in our history — we’ve been on 5 continents, in 16 countries and almost 40 US states and territories,” says Andrés via email.

WCK credits its responsiveness to its ability to prioritize urgency. Their team understands that hunger requires immediate attention — there isn’t time to wait for ingredient approvals or fill out forms or navigate other bureaucratic hurdles. Instead, their staff and volunteers deploy as quickly as possible to disaster zones and work directly with those affected. The latter is a principle that’s central to their organization. “Everywhere we go, we get the same amazing lesson: A community knows what it needs, and we can achieve so much more when we listen to those needs and empower people to act locally,” says Andrés.

Another distinguishing feature of WCK is its ability to flex and adapt, something that many relief organizations and workers aren’t able to do. “You gotta be willing to go outside of the box and not wait around for somebody else to have the answer,“ says WCK CEO Nate Mook.

Mook joined WCK after leading and developing its #ChefsforPuertoRico initiative in the aftermath of 2017’s Hurricane Maria where its team served 4 million meals to island residents. Since 2018, he has led the organization’s operations as well as its emergency and disaster-relief efforts. We sat down with him over Zoom to understand just how WCK gets meals to those who need them, no matter where they are.

Get eyes on the ground ASAP

The first step to helping people in a crisis is to find out exactly what they’re facing. When an unexpected tragedy occurs, WCK dispatches an initial assessment team to the scene to understand exactly what happened and what is needed. The explosion in Beirut’s Port on August 4, 2020, was a perfect example. “We didn’t know what the situation was,” says Mook. “But we knew the damage was big, we knew that a lot of people were probably displaced, we knew that a lot of folks probably weren’t going to have electricity for a while, and we knew that a lot of restaurants, grocery stores and businesses were destroyed or damaged. But until you get on the ground, you know nothing.”

The humility of admitting they know nothing is essential to WCK’s work — leaving them open to input about how they can be most helpful and effective. Within 36 hours of the explosion, WCK had two members on the ground, who immediately connected with locals. “Their job is to put eyes on the situation, go to the places that were impacted, talk to the local leaders in those areas,” says Mook. “In Beirut, we connected with a bunch of local nonprofits that worked there.” They were able to determine where people were displaced, what the gaps were in terms of access to food, as well as what other organizations were already doing. These initial assessments are integral, because they reveal how urgent a situation is and how much effort and coordination is required on WCK’s part.

While an explosion is impossible to predict, extreme weather events like hurricanes can be tracked and monitored, which provides WCK with a huge advantage. “When it’s a hurricane and we roughly know what’s coming, we can pre-stage,” says Mook. “We can get people on the ground, set up a kitchen , and get everything ready to go. As Hurricane Florence hit North Carolina in September 2018, we were cooking as it was still hitting, delivering meals to shelters, firefighters, police and the emergency operation center.”

Lead with empathy

“Some of us assume that everyone has 72 hours of food in their house, but the reality is that a lot of people don’t,” says Mook. “When the grocery stores, electricity and water are all out, food is something you need now — it can’t wait until tomorrow or the next day.”

A guiding principle for WCK is to lead with empathy. This includes recognizing that not everyone is able to evacuate during a disaster. Some don’t have the resources to flee or they may not be physically mobile or they may not want to leave their home behind. WCK recognizes they’re on the scene in service to a community — not just giving to them. “It’s a subtle shift, but I think it is so critical,” says Mook.

Another part of leading with empathy is recognizing that not everyone is able — or ready — to ask for help. “It is not an easy thing to say: ‘I need your help,’” explains Mook. The WCK team has learned to be more pointed in their inquiries. Mook says, “You ask questions, like ‘What’d you eat today?’, ‘What are your kids eating right now?’, ‘What type of food?’, and ‘Do you have enough water?’ Once you start asking these questions, then everything starts to crumble and you realize people need support.”

No need to reinvent the wheel — just add to it

Mook says WCK looks for smart and effective solutions that are already available on site, instead of introducing new ones. When Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017, the island was devastated. Neighborhoods were demolished, electricity was wiped out, and residents needed food and water. Humanitarian responders like FEMA tried to ship bread over from the mainland US, but they faced hurdles because many ports in Puerto Rico had been destroyed.

WCK took a different approach altogether. “We just said, ‘Well, how about we make sure that the local bakeries have fuel for their generators, fresh water and ingredients so they can start producing bread on the island again?’” recalls Mook. “That type of thinking is a no-brainer, right? Yet it’s often not how things are done.”

An important question that WCK always asks: “What and who are already there?” Their teams connect with community members and map resources by finding out the locations of local suppliers and kitchens and who already has access to food. “We make phone calls to chefs, and that’s what’s amazing about the chef community,” says Mook. “You make a phone call to somebody who makes a phone call to someone else, and before long, you’re connected with all the chefs in that area.”

During August’s Hurricane Laura, mapping resources was important. Nobody knew exactly where Laura would make landfall, but WCK wanted to prepare itself. So they sent some team members already based in Louisiana to Lake Charles, a city that was predicted to be in the storm’s path. They ended up staying the night at a local casino, connected with its management, toured the space including its kitchen, and let management know about WCK’s work.

When Laura hit Lake Charles, says Mook, “we immediately reached back out to the casino.” Because the casino didn’t have water or power, WCK’s team got hold of a food truck — using it as a mobile relief kitchen — and started serving meals out of a parking lot. A few days later, after the casino had generators and access to clean water, casino staff contacted WCK. “They said they weren’t opening the casino to the public, so come on in,” says Mook. “Within four days, we had accommodations at the casino, we had a massive kitchen there, and we were able to tap into local knowledge and local resources.”

In recent times, much of WCK’s work has been driven by the climate crisis. “We find ourselves responding to more and more climate disasters each year — the wildfires up and down the West Coast of the US are getting worse, the Atlantic hurricane season is longer and more destructive, and climate change will continue to cause more tragedies around the world,” says Andrés. “But what drives me is knowing that, after the storms clear and the fires are extinguished, there’s a real opportunity to build resilience into a community against future disasters.”

Benefit from knowledgeable volunteers

While WCK’s main office is based in Washington DC, its full-time staff — consisting of roughly 50 people — is located all over the world. It also relies on a global network of passionate contractors and volunteers. The volunteers are a mix of people local to the disaster area but also include seasoned supporters, such as a retired chef named Elsa, who fly in to help. “She’s not an employee at World Central Kitchen, but she’s part of the family,” Mook says warmly. Elsa is based in California, and she started working with WCK during wildfires. Since then, she’s travelled all over the world with them. This September, she led the feeding operations for the California wildfires. WCK covers the costs of all their food and non-food supplies by using funds raised from individual and corporate donations.

After an initial WCK team assesses the damage and the resources available in a disaster area, a WCK chef relief team comes in to get the work started. Experienced helpers like Elsa know how to keep operations going by organizing the local volunteers who frequently step up to help their neighbors in need. “After a disaster, people in the community — folks who aren’t as worse off as others — want to come in and volunteer,” says Mook.

Once the local volunteers are established, the WCK personnel can slowly pull back. They’ll oversee operations for a few weeks, and when things are relatively stable, they’ll shift their teams to the next place in need. After spending a few weeks in Louisiana in August, the WCK teams moved onto Oregon to help those affected by wildfires.

Get ready to toss out established ways of doing things

Even though WCK has their own tried-and-true methods for doing their work, they recognize that every disaster is different. “The first rule of feeding people is adapting to the circumstances,” according to Mook.

Sometimes, that can mean recognizing what people need is not what you’re used to providing. “When we were in the Bahamas responding to Hurricane Dorian [in August 2019], we were having to deal with water filtration and getting water to places for a short period of time,” says Mook. “We were also performing medical evacuations. We’d go in with a helicopter to drop off food, and we’d bring back people [and take them to medical care]. In a disaster, you gotta be willing to make those quick decisions and you can’t expect somebody else to come in with the answer. You have to say, ‘You know what? I’m going to figure out what I can do and then do it.’”

Adapt yet again when the unexpected — an ongoing pandemic — happens

Of course, one of the most challenging crises in 2020 has been the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike natural disasters, which tend to be concentrated in a single area, the pandemic affected most of the world, making it hard to figure out where to begin. WCK realized it couldn’t be everywhere so they pivoted again. “Normally, when we work with restaurants, we partner with them or take over their restaurant and set up a big kitchen operation there and it becomes our operation,” explains Mook. “In this case, what we said is ‘You do what you know how to do — you do the meals, you buy from your suppliers, you manage it. I’m just going to tell you how many meals I need and where it needs to go. So that was a very new thing for us, because we weren’t the ones doing the cooking.”

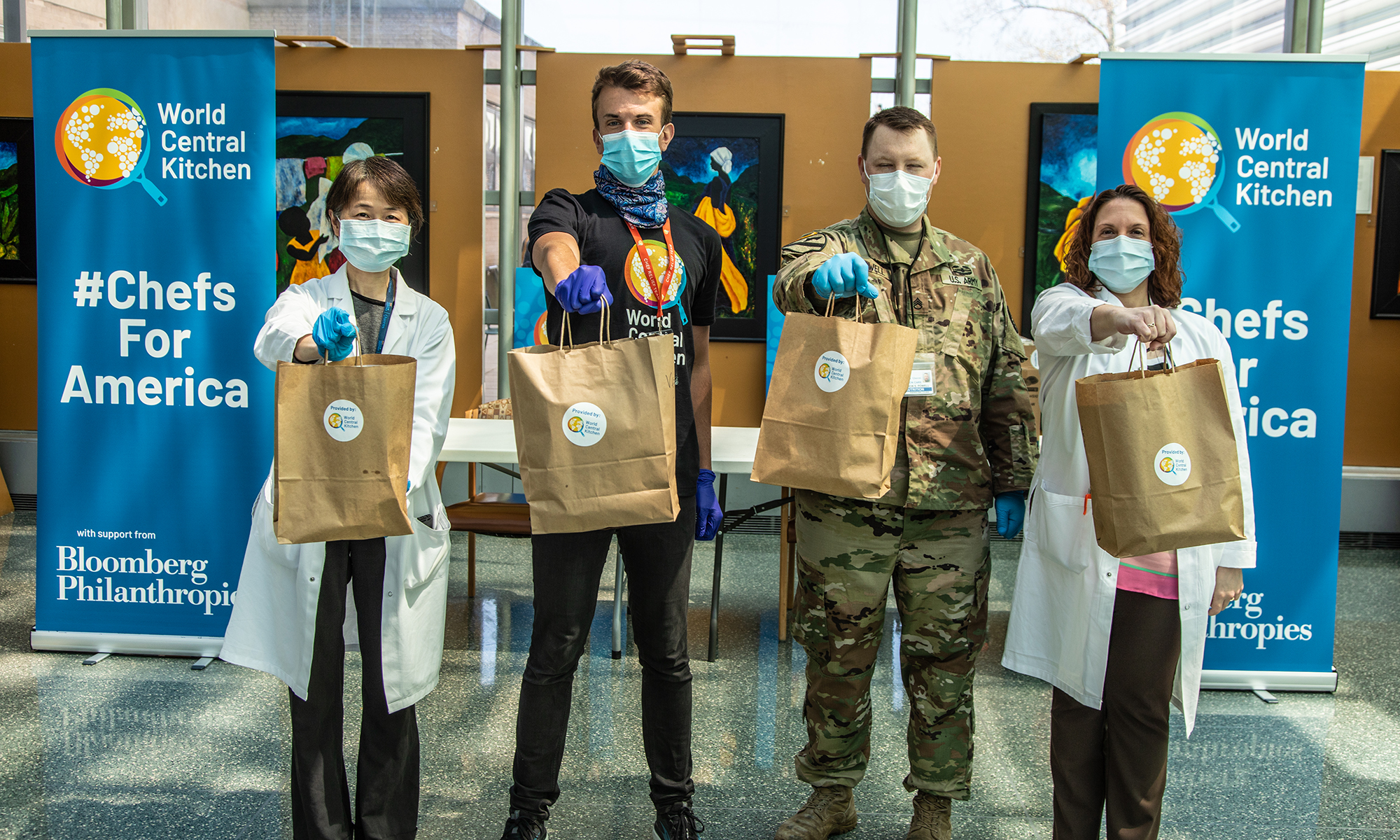

WCK’s Restaurants For The People has two goals: Keeping small restaurants and food businesses open while providing fresh meals to first responders, front-line workers and those struggling with hunger. WCK has worked with over 2,000 restaurants in 400 cities in the US, directly disbursing over $135 million to them and serving over 12 million meals to people who need them. And the program has had positive ripple effects, with demand from restaurants helping keep farmers, fisheries and ranchers in business.

For Andrés and WCK, regardless of the number of disasters that life brings, they’re committed to innovating and pushing forward. “At the beginning of 2020, we had no idea what the year would bring, and now our team of chefs, relief workers, volunteers and supporters has grown bigger beyond even what I could have dreamed,” says Andrés. “When I founded the organization in 2010, we knew there were big opportunities to change the way that disaster relief is done and we’ve just started to scratch the surface of those changes. There is one thing I know, which is what drives our team every single day: Wherever hungry people need to eat, we will be there.”

All images: Courtesy of World Central Kitchen.

World Central Kitchen is the recipient of a grant from The Audacious Project, a collaborative funding initiative that is unlocking social impact on a grand scale. Every year The Audacious Project — which is housed at TED — selects and nurtures a group of bold solutions to the world’s most urgent challenges and gets them launched thanks to an inspiring group of donors and supporters.

Watch José Andrés’s 2017 TED Talk here: