Marine biologist Stephen Palumbi picks 10 of his favorite underwater creatures. From the oldest living animal to the fastest food in the sea, they’re all pretty extreme.

Marine biologist Stephen Palumbi (his new TEDxStanford Talk is The Extreme Life of the Sea) knows a lot about what goes on beneath the world’s waves. Palumbi is the director of Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, where he is mapping the genome of sea corals. As a scientist, professor and researcher, he has also shown the value of DNA identification in whale conservation and in seafood markets (see his TED Talk: The Hidden Toxins in the Fish We Eat) and traced the variation in sea urchin sperm shape. (How about that for dinner conversation?) His recent book The Extreme Life of the Sea — written with his son, novelist Anthony Palumbi — shines a light on the wild world of sea life. Recently we asked Palumbi to share some of his favorite sea creatures — from the obscure to the fascinating to the just plain strange. He gracefully obliged. Below, his top 10 picks:

1. The sailfish

Sailfish are the fastest eaters in the sea. They can move at 40 miles per hour — powering through schools of fish, stunning them with blows from their bills, and gulping them down on the fly. Their eyes and brains have to work so fast at these speeds that they need to be heated up, using specialized heat-generating muscles that line the eyes and brain. Photo: iStock.

2. The bowhead whale

The bowhead whale is the oldest living mammal. This was proven by the discovery of century-old brass harpoon tips embedded in scars on the backs of whales hunted in the 1990s. These harpoons haven’t been thrown at whales for over a century. Thus, the very same animals hunted in the 1990s also survived human attacks 100 years ago. Photo: Paul Nicklen/Getty Images.

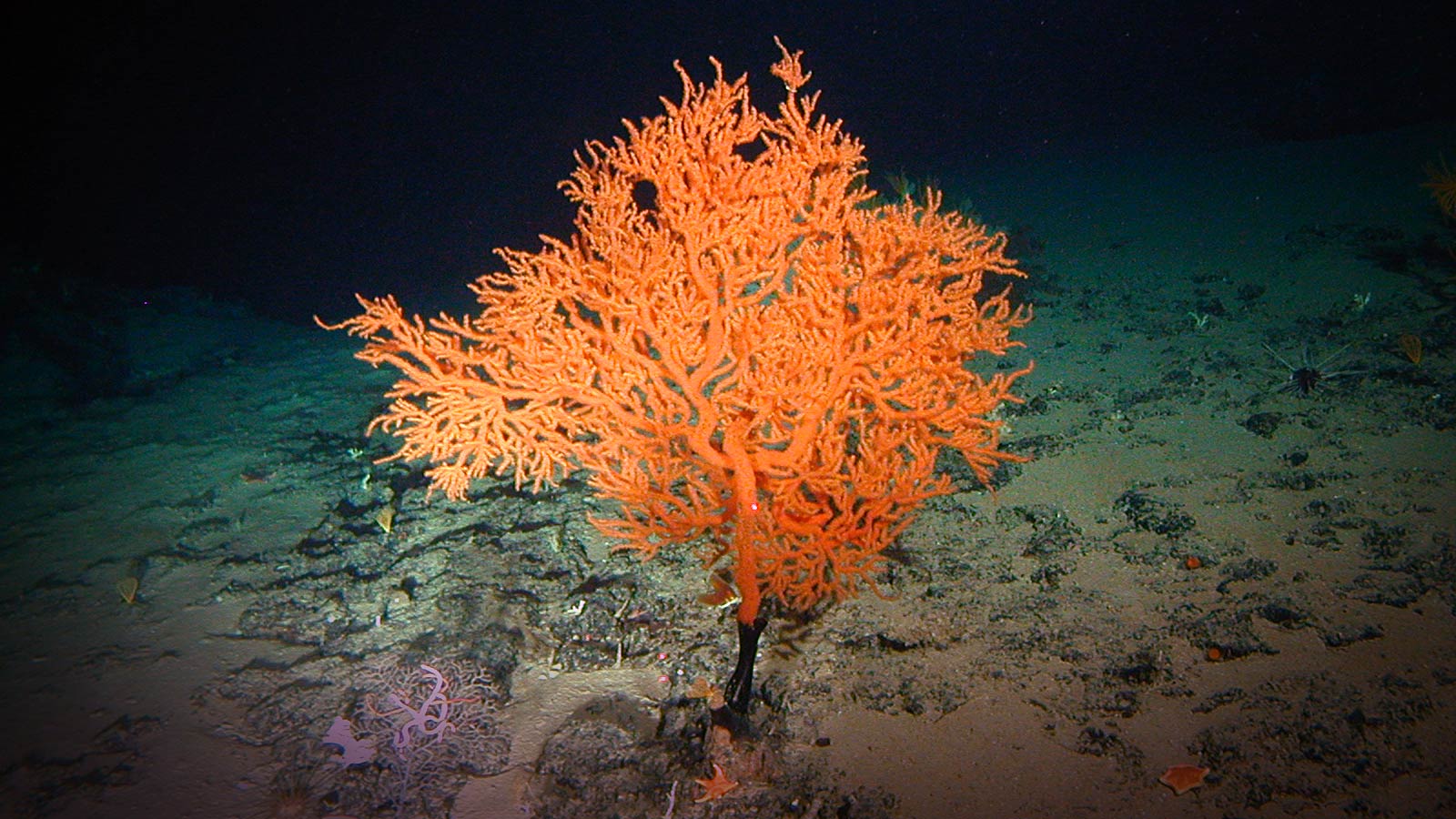

3. The coral leiopathes (deep water black coral)

The oldest known animal is a coral living on the slopes of Hawaii — deep in the sea, thousands of feet below the surface, where conditions are dark and cold and slow. These black corals grow a hair’s width a year. The oldest is now known to have lived longer than any other animal on Earth — 4,270 years. Before some of the Egyptian pyramids were built, this coral was alive. Photo courtesy of NOAA Hawaiian Undersea Research Lab.

4. The Pompeii worm

The animal with the largest temperature tolerance is the Pompeii worm, which lives at the undersea hot-water vents, where hot water at immense pressure billows out from under the earth’s crust. The worm’s tail sits at the temperature of hot tea, but its tentacled head — an inch away — dips into the ice-cold water of the deep sea. To learn how this amazing creature constructs its cells and proteins across such a temperature range, the genome of the Pompeii worm is being decoded. Photo courtesy of University of Delaware College of Marine Studies.

5. The humpback whale

One of the most exuberant animal displays in the ocean is the breaching of humpback whales. The huge fins on humpback whales were once thought to generate huge drag forces on the whales because the fins are so long and so bumpy. But detailed testing has shown the bumps actually reduce the drag forces generated by the fins. Similar designs on fan blades have resulted in a new generation of low-drag, high-efficiency products. Photo: iStock.

6. The beluga whale

Beluga whales have some of the best sonar in the sea. Their swollen head houses the ‘melon’, a fat-filled space that focuses incoming sound waves. Belugas need this extra acuity. They live among drifting ice in narrow channels, and they need to use sonar to see ice holes that they can breathe through. Photo: Jenny Spadafora (jspad)/Flickr.

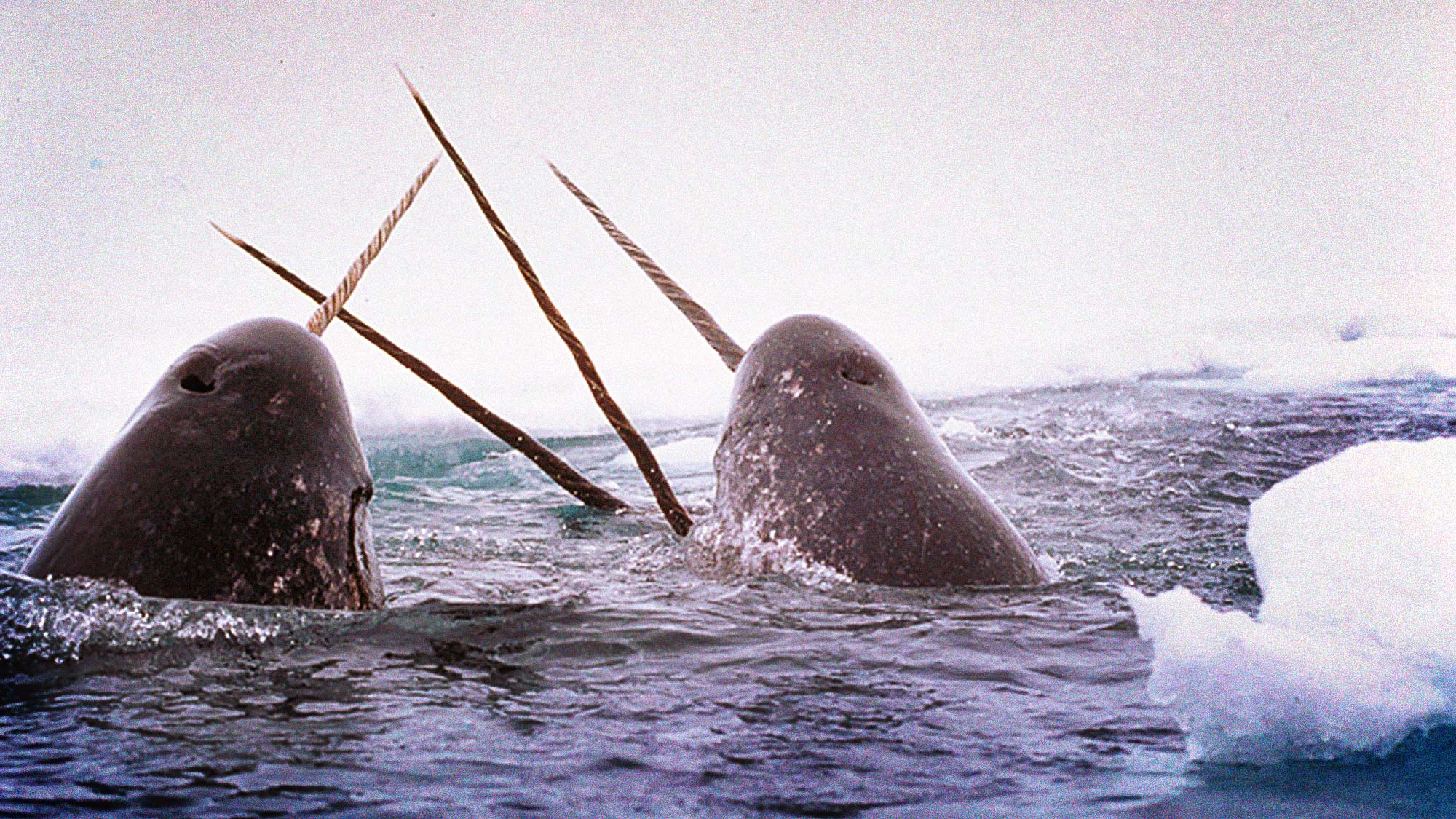

5. The narwhal

Narwhals gave a legendary boost to the Middle Ages — as unicorn horns. The tusks of narwhals were collected in the polar reaches of the North Atlantic and sold around Europe to nobles and collectors. Drinking from a “unicorn horn” was said to prevent poisoning. Each tusk is a tooth, overgrown from the side of the mouth, but extending 10 to 14 feet in length. Tusks have no known function — but there are two clues for future marine biologists: Most males have tusks, but few females do. And some narwhals have two. Photo: Glenn Williams/National Institute of Standards and Technology.

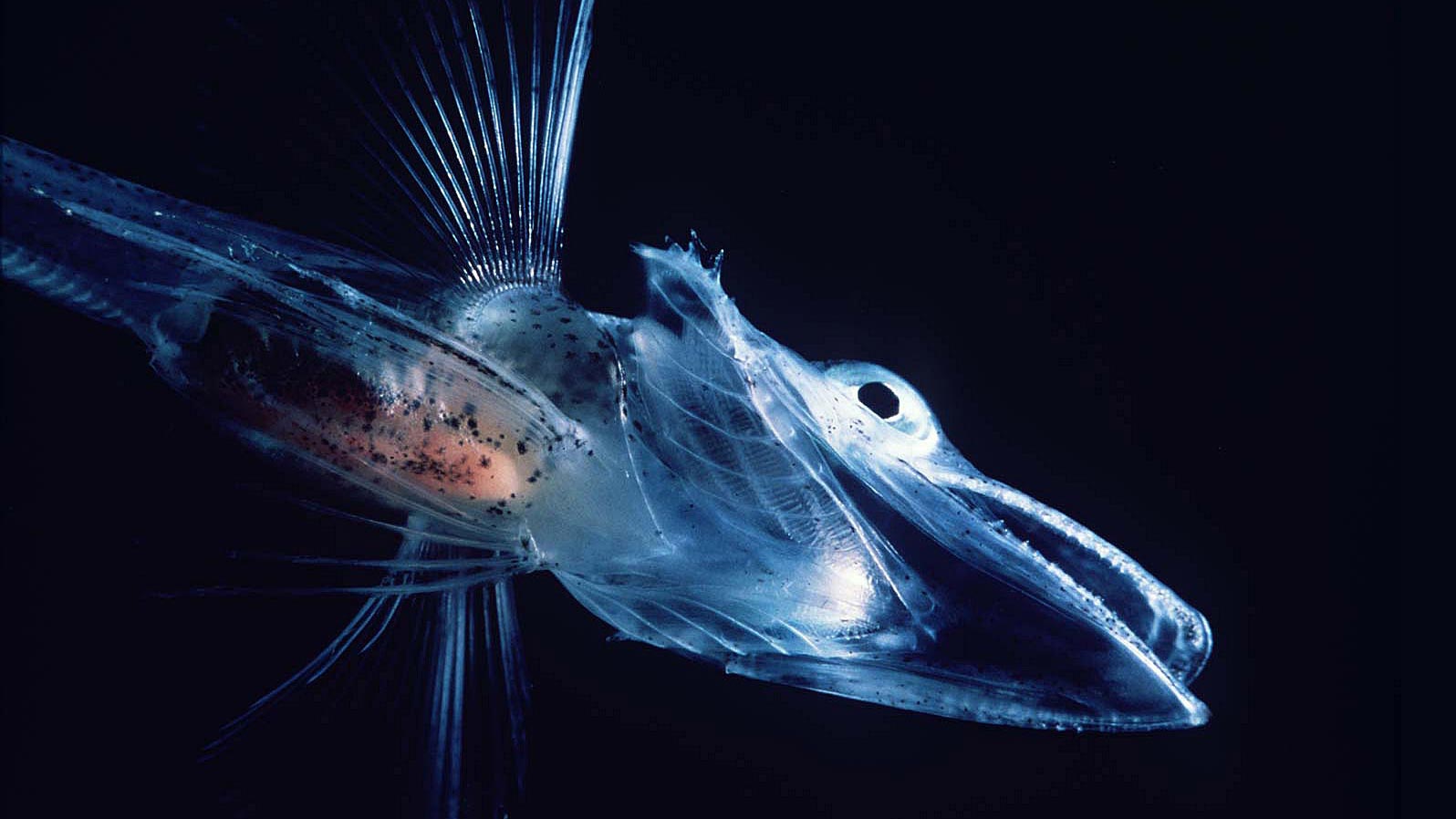

8. The icefish

The Antarctic icefish live in water colder than freezing — 2 degrees below zero Centigrade. Ocean water doesn’t freeze at this temperature because it’s full of salt. The blood of the icefish is less salty than seawater; instead, it keeps itself from freezing by using ice proteins, sometimes called antifreeze proteins, that attach to ice crystals forming in the blood stream. Once the ice crystals are coated with antifreeze protein, they can’t stick together, so they don’t grow. The icefish of the Antarctic have used this adaptation to become very successful — making up 95% of the fish biomass around Antarctica. Photo: Uwe Kils/Wikimedia Commons.

9. Clownfish

Clownfish families were made famous in ‘Finding Nemo,’ but real ones have more peculiar lives than the movie lets on. In a sea anemone where the clownfish live, the biggest fish is always a female, laying all the eggs. The next biggest fish is a functional male, fertilizing them. And lots of smaller clownfish are immature males. When the female dies or is eaten by a predator, the biggest male switches sex to become female. At the same time the biggest immature male grows into a functional male that can fertilize the eggs. This conveyor belt system of parenting assures a constant supply of baby Nemos. Photo: Nick Hobgood/Wikipedia.

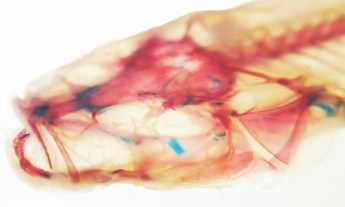

10. The anglerfish

Anglerfish inhabit the deep sea, and for a century they baffled marine biologists. At first only female anglerfish were known; where the males were and what they looked like was a complete mystery. Then a parasitologist began studying the worm-like parasites generally attached to anglerfish females. What he found, instead of parasites, were anglerfish males — each undergoing a radical transformation. When a male anglerfish is tiny, he finds and attaches to a female. First his jaws dissolve and his bloodstream fuses with the female’s. Then his brain disappears and his guts shrink. Eventually he is little more than a testis, fertilizing the eggs of one female, for the rest of his life. Photo courtesy of Edith Widder.

TED speakers regularly cover extreme sea creatures and what’s happening underwater. Catch just some of their talks here:

[ted id=833]

[ted id=206]

[ted id=264]

[ted id=830]

Featured image courtesy of Edith Widder.