Secret prisons reflect a parallel legal system for prisoners who are denied access to communications, deprived of their due process rights, and hidden from public scrutiny. Investigative journalist and TED Fellow Will Potter explains.

Secret prisons are operating in the United States today. Many Americans I speak with don’t believe this could possibly be true, and think that such human rights abuses only occur in foreign countries. But the reality is that the United States has a dark history of disproportionately punishing people because of their political views, a history that has largely been ignored or forgotten.

Today, under the ever-growing banner of national security and the “War on Terrorism,” that trend has continued in secrecy.

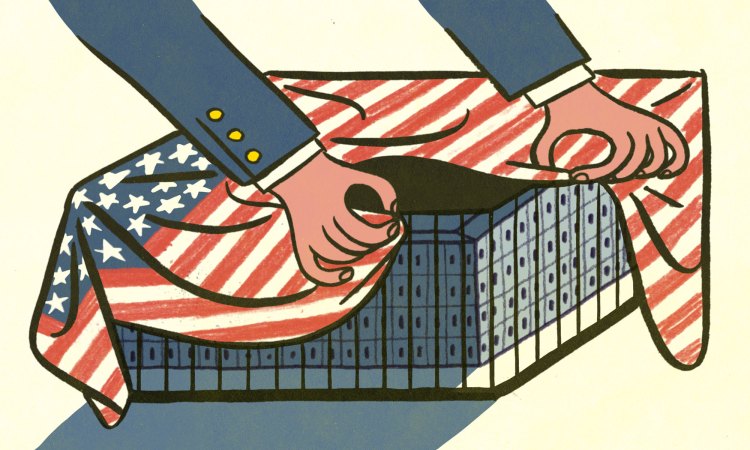

Let me be clear about the term “secret prisons,” though. I don’t mean facilities the public has absolutely zero knowledge about. After all, even Soviet gulags were known both within the country and internationally. Secret prisons are those that operate under a separate standard from traditional prisons. They reflect a parallel legal system for prisoners who, whether because of their race, religion, or political beliefs, are denied access to communications, deprived of their due process rights, and hidden from public scrutiny.

Here, then, is a brief look at that history, from institutions started in the 1940s to those that are operating today.

Japanese internment camps

Perhaps the most notorious use of this parallel legal system was the internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. All Japanese adults were required to complete a questionnaire to evaluate their “Americanness,” and the final two questions directly assessed their loyalty to the United States.

Leading up to the internment, the government had begun using a “Custodial Detention Index” to identify and surveil political activists, including those in the Japanese community. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the FBI carried out arrests of many of these individuals and sent them to detention camps as well.

Alcatraz

Around this time, Alcatraz was becoming a household word. The former military garrison was described as the “end of the line” and the nation’s most repressive prison. It housed the so-called “worst of the worst,” including gangsters like Al Capone. But Alcatraz was more than that. It was a new spectacle of retribution and secrecy. It was an island far removed from public oversight, both geographically and politically. Prisoner accounts detailed widespread brutality, and said that most torturous of all was Warden Johnston’s “silence rule,” which prohibited all communication by prisoners. It reportedly drove several prisoners insane.

Public perception of Alcatraz was that it housed violent prisoners unworthy of public consideration. It also housed some of the most controversial political prisoners of the era. Morton Sobell, for instance, was a co-defendant of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg—who were executed for conspiracy to commit espionage against the United States—and the focus of public outreach and media efforts to secure his release. Rafael Cancel Miranda was an influential figure in the Puerto Rican independence movement. Like prisoners in the modern-day Communications Management Units I visited, Cancel Miranda was only allowed visits between glass and conducted in English. He was not allowed to see his children.

USP Marion

In 1963, USP Marion was created as a high-tech replacement for Alcatraz, and 500 of its prisoners — including Miranda — were transferred there. In 1968, prison officials began a behavior modification program at Marion called the Control and Rehabilitation Effort, with the Orwellian acronym of CARE. Prisoners characterized CARE as psychological attack sessions. When prisoners protested the beating of a fellow inmate in 1973 by organizing a work stoppage, prison officials created an even more extreme program at Marion called the Control Unit.

Over the years, the Marion, Illinois, prison became infamous for this Control Unit, which kept prisoners in solitary confinement on lockdown for twenty-two hours at a time. There were accounts of widespread brutality. National organizations called the “Marion Model” tantamount to psychological torture, but the Bureau of Prisons claimed that it was necessary to maintain safety.

Like Alcatraz, though, the Control Unit did not house prisoners solely based on their propensity for violence. As former warden Ralph Arron told Mother Jones in 1990, “The purpose of the Marion Control Unit is to control revolutionary attitudes in the prison system and the society at large.” After a prison-wide strike and then the murder of two guards at Marion in the early 1980s, the entire prison effectively became a Control Unit. Later, government officials called for an even more extreme facility, and the Supermax ADX-Florence was built in Colorado.

Lexington HSU

In the 1980s, a similar unit was created for women. The High Security Unit in the federal women’s prison in Lexington, Kentucky, was created to house political prisoners belonging to any organization that, according to the Bureau of Prisons, “attempts to disrupt or overthrow the government of the U.S.” The unit housed Susan Rosenberg, a radical activist who supported the Weather Underground and Black Liberation Army, and Silvia Baraldini and Alejandrina Torres, who supported Puerto Rican independence struggles.

The Lexington HSU existed belowground, in total isolation from the outside world and with radically restricted prisoner communications and visitations. The women were subjected to constant fluorescent lighting, almost daily strip searches, and sensory deprivation. The purpose of these conditions, according to a report by Dr. Richard Korn for the ACLU, was to “reduce prisoners to a state of submission essential for ideological conversion.” The Lexington HSU was closed in 1988 after protest by Amnesty International, the ACLU, the Center for Constitutional Rights and religious groups.

Barrington Parker, the judge in this case, said that the prison units were illegal because they disproportionately punished political dissidents. “The designation of prisoners solely for their subversive statements and thoughts is the type of overreaction that the Supreme Court has repeatedly warned against,” he said in his ruling.

Communication Management Units

And yet the closure of the HSU was hardly the end of the story. Today, Communications Management Units, or CMUs, are the modern extension of the Bureau of Prisons’ history of operating pilot programs outside the confines of the Constitution. In April 2006, the Justice Department proposed new rules for “Limited Communication for Terrorist Inmates.” Proposals included limiting prisoner communication to one fifteen-minute telephone call per month, one six-page letter per week and one one-hour visit per month. During the required public comment period, civil rights groups protested that the program was inhumane. The backlash prompted the government to drop the proposal. Or so it seemed.

A few months later, the Justice Department quietly opened the first CMU in Terre Haute, Indiana. Two years later, they opened another in Marion, Illinois.

In October 2011, the U.S. Bureau of Prisons reported that federal prisons house 362 people convicted in terrorism-related cases. However, the government will not disclose who is housed in the CMUs, why they were transferred there or how they might appeal their designation. CMUs are intended to isolate prisoners with “inspirational significance,” to use the government’s language, from the communities and social movements of which they are a part. These secretive prisons are for political cases the government would rather remove from the public spotlight.

Even federal judges sometimes don’t know about the CMUs. Attorneys for environmental activist Daniel McGowan, sentenced in 2007 to seven years in jail for his role in two acts of arson, argued in court that if he was sentenced to prison as a “terrorist,” he could end up in a secretive prison unit. Judge Ann Aiken replied, “Now, defendants raise the specter that anyone with a terrorism enhancement is automatically doomed to a dungeon, so to speak, at the U.S. Penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana. It’s a very emotional argument, but nothing more, because it’s not supported by the facts.” In a way, Aiken’s comments are true. The argument was not supported by facts, because it was incredibly difficult to learn the details of these prison units.

That’s still the case today. I was able to visit Daniel McGowan in the CMU, making me the first and only journalist to visit the facility. As I detailed in my book, Green Is the New Red, prison officials threatened to punish McGowan if I interviewed him, and later punished him for writing about the units for the Huffington Post.

Black sites

Secret prisons aren’t only housed within the United States. Abroad, the CIA has operated “black sites” — facilities that were used to interrogate and torture people outside the scope of the American judicial system. The Guantánamo Bay detention camp, which has become synonymous with indefinite detentions and human rights abuses since it was opened in 2002, is likely the most famous of these. A 6,700-page government report details the scope of these operations and the CIA’s use of torture. But right now, the report is being kept hidden, even from members of Congress and government officials. As the New York Times noted, “the Justice Department has prohibited officials from the government agencies that possess it from even opening the report, effectively keeping the people in charge of America’s counterterrorism future from reading about its past.”

Homan Square

This notion of a parallel legal system has crept into local law enforcement as well. In Chicago, the police department is operating an interrogation compound called Homan Square. It is off the books, which means that Americans locked inside are not listed in police databases and cannot be found by friends and family.

As Spencer Ackerman reported for The Guardian, arrestees are denied access to attorneys, and some have reported police beatings. The facility is a nondescript warehouse on Chicago’s west side, where people are held in interrogation rooms for between 12 and 24 hours. Unlike at the police precinct, no one is booked and charged here, and lawyers are turned away at the door.

“It brings to mind the interrogation facilities they use in the Middle East,” said arrestee Brian Jacob Church, one of the so-called NATO 3 arrested in the leadup to mass protests in Chicago in 2012, who spent 17 hours in the facility. “It’s a domestic black site. When you go in, no one knows what’s happened to you.”

There is a common thread between all of these secret prison units, both foreign and domestic, past and current. They reflect the slow, steady dissolution of core constitutional rights in the name of national security.

When the CMUs were opened, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, Harley Lappin, testified before the U.S. Congress that they were for “second-tier” terrorism inmates. “We do not have to have them as restricted, but we want to control their communications,” he said. This benign characterization of these prisons is a chilling reflection of how, bit by bit, year by year, post-9/11 rhetoric of terrorism and national security have swelled into a form most Americans think can only occur in other countries.

If there is one thing that should be learned from history, from governments that have gone down this path, it is this: secretive prisons for “second-tier” terrorists are often followed by secretive prisons for “third-tier terrorists” and “fourth-tier terrorists,” until one by one, brick by brick, the legal wall separating “terrorist” from “dissident” or “undesirable” has crumbled.

This pattern is easier to identify when it occurs elsewhere or in history books. Restraint and reason have a way of surfacing with distance and time. The true challenge, though, is for Americans to shed this skin of exceptionalism we have worn, acknowledge that we, too, are vulnerable, and confront what is happening right now, at home.

Illustration by Hannah K. Lee for TED.