Most of the Caribbean’s coral reefs are in bad shape, victims of overfishing, sewage and fertilizer pollution, disease, rising temperatures, and reckless coastal development. But corals are deeply important for humans everywhere, not least because they are a source of food, they protect shorelines, generate tourism revenue — and provide chemical diversity through which scientists are discovering new medicines. That’s why they are worth hundreds of billions of dollars a year. And that’s why my colleagues and I at the CARMABI Research Station in Curaçao are focused on understanding how corals reproduce, and studying what we might do to help young corals build us the reefs of the future. Here’s a peek at our world underwater and our work studying one particularly important coral species.

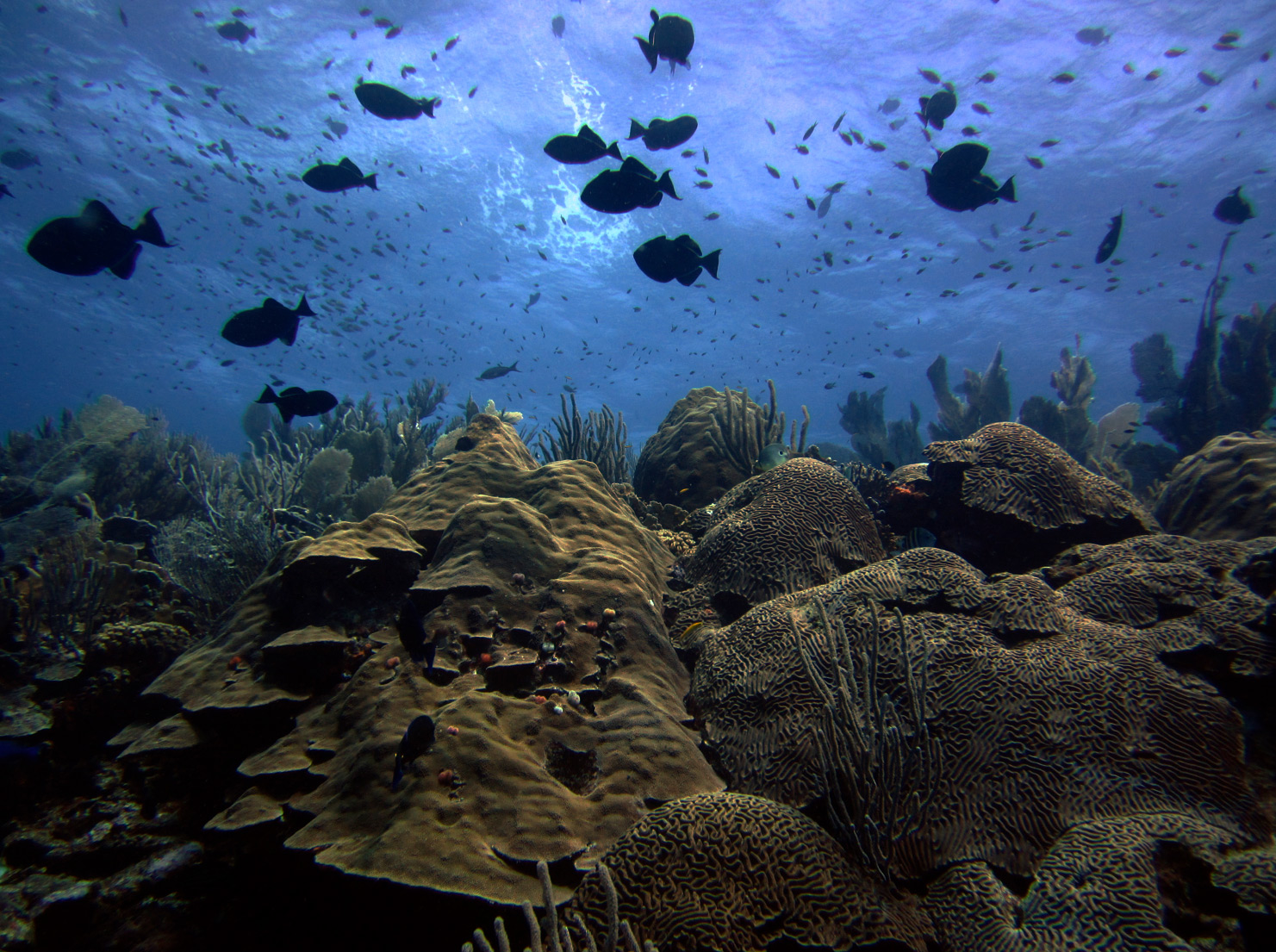

Meet the coral reef of Curaçao

Here’s the reef in Curaçao. The mountain-shaped coral in the foreground is an important reef-builder across the Caribbean that was listed as “threatened” by the U.S. Government in 2014. Each year in September, we study its reproduction during its annual mass spawning event. We dive for a few nights in a row, knowing that the biggest spawning event is usually seven or eight nights after the full moon. Photo: Mark Vermeij.

How we make homemade coral nurseries

A field season of studying coral reproduction usually starts with a lot of trips to the hardware store and a lot of wacky craft projects. Here are our coral spawning tents: a custom assemblage of plastic, glue, tape, funnels, zip ties, rocks, and collection tubes designed to sit over spawning corals on the reef without washing away, rusting, ripping, or hurting the corals. On a few specific nights each year, a couple of hours after sunset, we wrap these tents into bundles and haul them underwater to the reef. Photo: Emily Kelly.

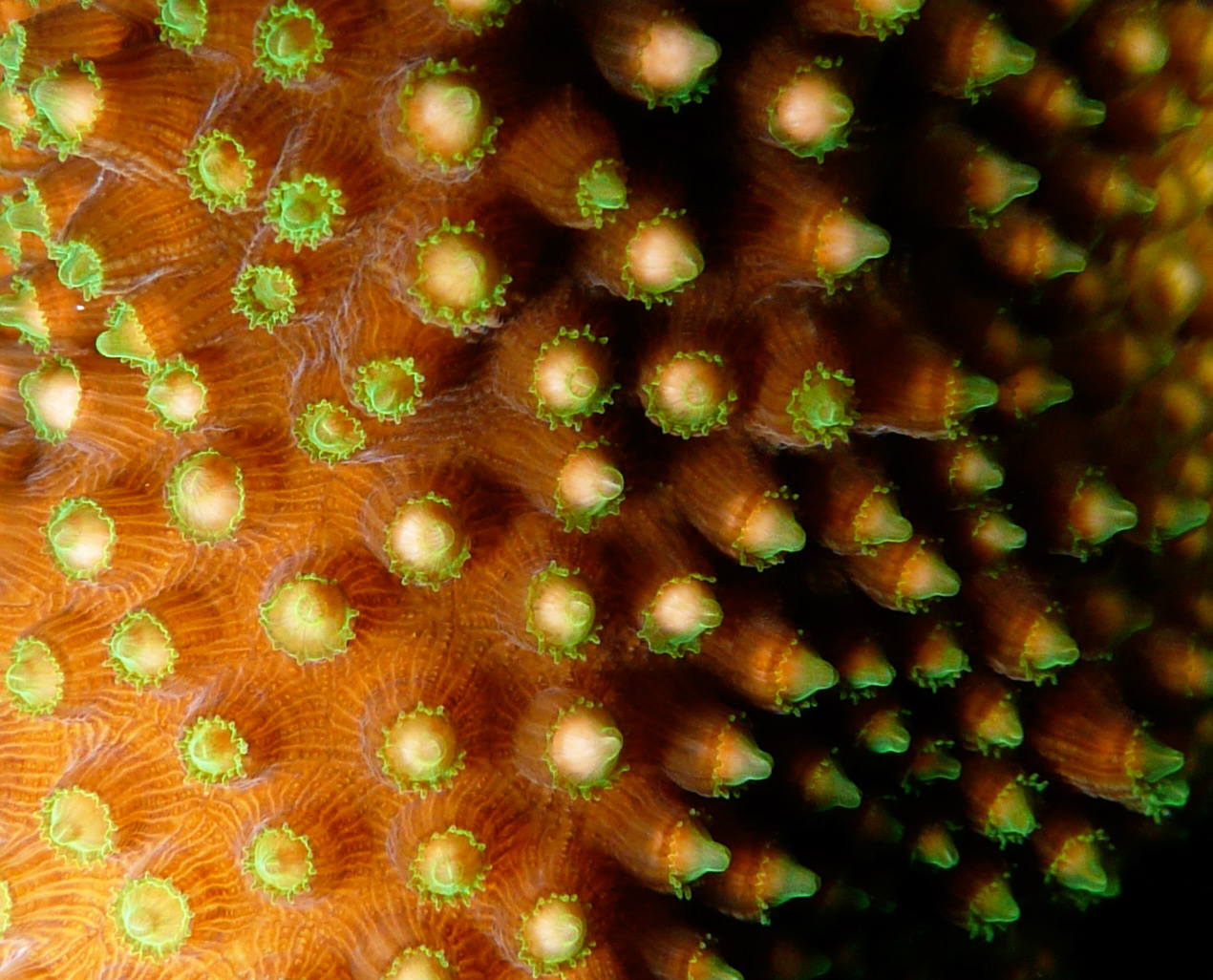

How to find a mate when you’re stuck at the bottom of the ocean

A coral reef is built by multiple coral animals, which live together in colonies. These colonies are formed by one original coral polyp — a mouth surrounded by tentacles — that divides itself in half over and over and over. All of these new twins stay connected to one another and build a skeleton underneath themselves, so that they can grow up toward the sunlight. The result is similar to a group of hundreds of tiny anemones living shoulder-to-shoulder on the surface of a rock. The star coral here is preparing to spawn, holding a bundle of gametes in each of its mouths (about 100 of them in this shot). The bright green color at the ends of the tentacles is produced by the coral’s own sunscreen-like pigments while the brown color is produced by the algae living inside the coral’s tissue. The light pink color is the gamete bundles, each made up of 50-100 eggs glued together with sperm. Yes, that’s right… they’re hermaphrodites. Not every coral is, but in this particular species each individual animal makes both eggs and sperm. But one individual coral colony can’t fertilize itself, so it still has to find a partner to mate with. How do you find a mate when you’re stuck to the bottom of the ocean? Most spawning coral species solve this puzzle by sending their sperm and eggs to meet at the water surface, cleverly turning a three-dimensional problem into a two-dimensional one. Photo: Kristen Marhaver.

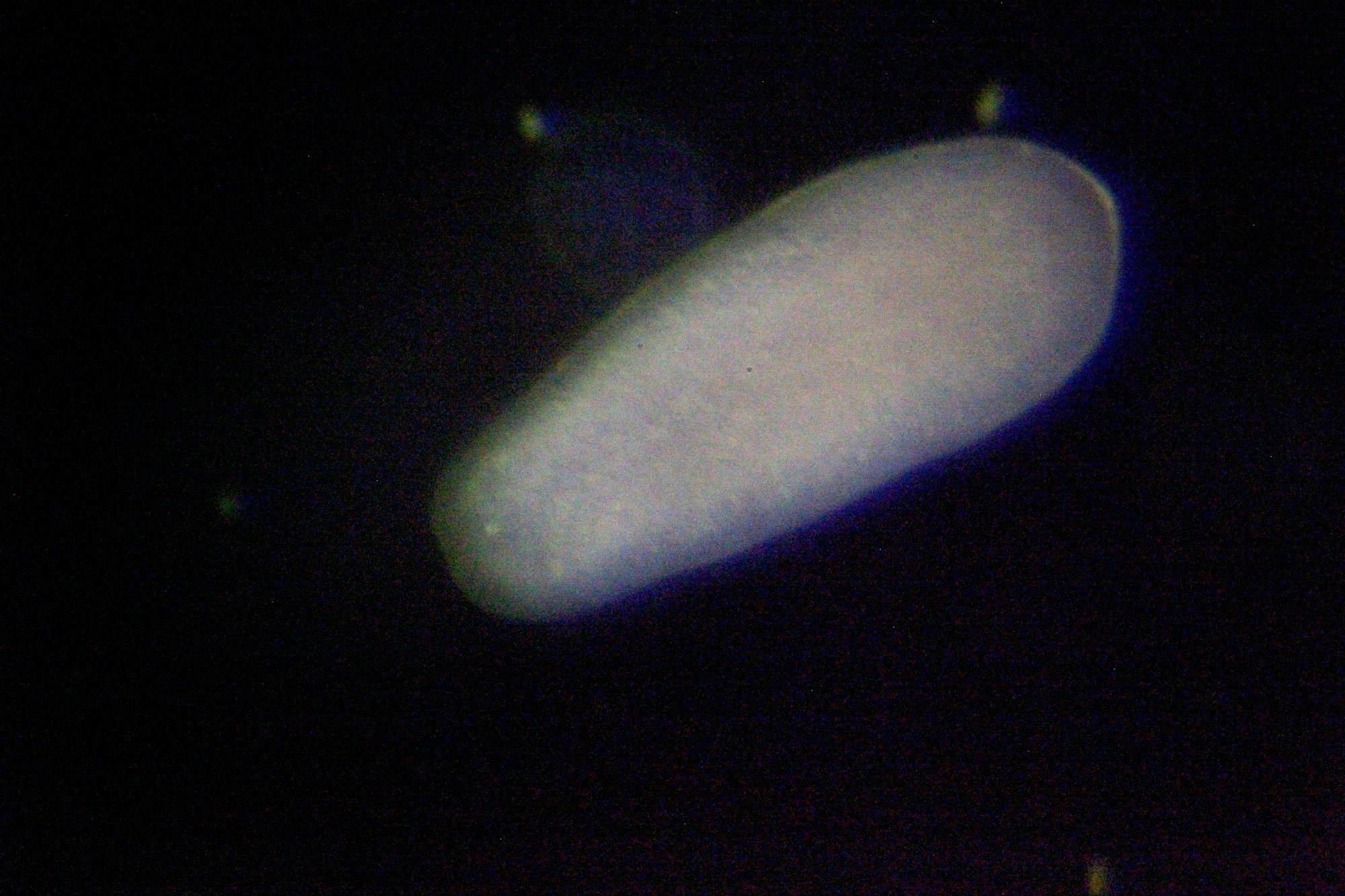

The synchronized mating ballet of star corals

Star corals synchronize their spawning times using the rising temperature of the seawater in the summer to choose the right month, the day in the lunar cycle to find the right night, and the local sunset time to find the right minute. They can’t do an elaborate mating dance, but their synchronized reproductive ballet is no less impressive. Across the reef, dozens of colonies all release their bundles into the water simultaneously. With the seawater swirling around, a diver has the surreal feeling of being inside of a snow globe. Although they’re animals, corals typically don’t display a lot of obvious behaviors, especially during the day. And then in one minute, at night in September, they throw a flamboyant confetti party. Photo: Kristen Marhaver.

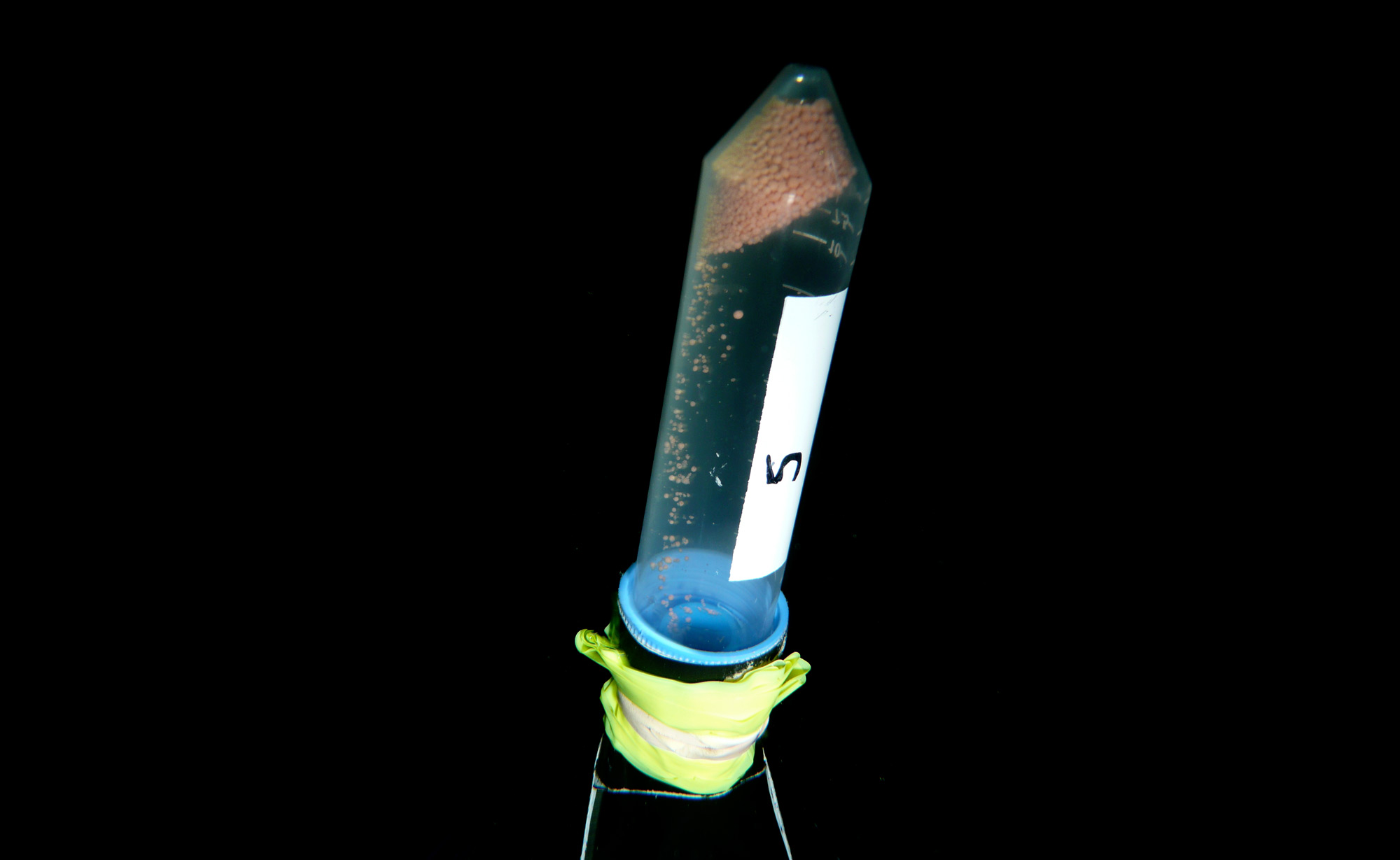

Coral egg and sperm donations — in the name of science

Each year, a few coral colonies help us with our research by spawning underneath one of our collection tents and donating their eggs to science. (Thank you, corals!) The egg-sperm bundles are buoyant; they rise slowly in the seawater thanks to the large amount of fat in the eggs. Once the corals spawn, we make sure the tents aren’t wrinkled or pinched around the colonies as we wait for the bundles to rise into the collection tubes at the tops of the tents. We can collect a few hundred or even a few thousand bundles in a single tube (we’re always careful to collect only what we can work with). At this point, we are also swimming around underwater taking photographs, surveying how many colonies are spawning, coordinating tasks between divers, and even cheering through our scuba regulators. Photo: Kristen Marhaver.

How to build a coral colony in the lab

In Curaçao, the star corals spawn at about ten o’clock pm. Underwater in the dark, with just a couple of small flashlights, watching bundles of coral eggs flow upwards into the collecting tubes is one of the most thrilling moments of the year. It means the corals spawned again! It means we timed it right! It means the species is still making eggs and sperm, despite all of the stresses we humans have dumped on them! And it means it’s about to be a LONG but exciting night in the lab. When the corals have mostly finished spawning, we remove the collecting tubes, cap them, and swim back to shore. In the parking lot near our cars, with care and excitement, we mix the egg-sperm bundles from different parents; on a big spawning night, bundles from as many as 20 colonies go into the mix. Meanwhile, other divers help collect the tents and bring them back to shore. Photo: Kristen Marhaver.

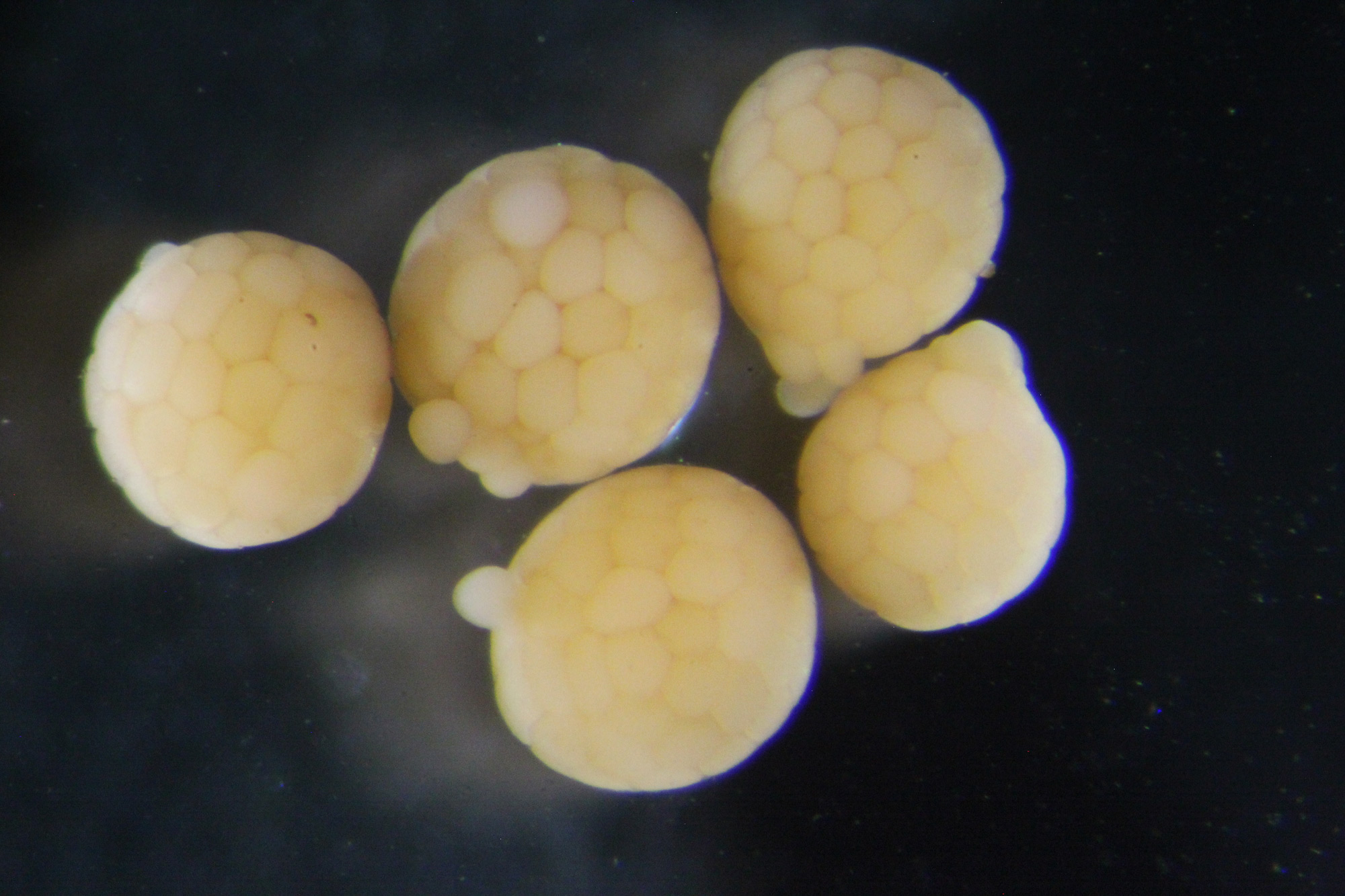

Watch in wonder: The birth of a coral polyp

The gamete bundles from the star coral are perfectly round and a pinkish-orange color (in other words, a beautiful shade of… coral). The sperm and egg cells are only viable for an hour or so, beginning when the bundles break apart at the surface of the ocean. Back in the lab, we can watch this process under the microscope. The bundles in this picture are just beginning to break up: the tiny clouds of sperm are visible and a few eggs are starting to separate. It’s amazing to see, and humbling to work with; each bundle is the entire reproductive effort for a coral polyp for the entire year. Photo: Kristen Marhaver.

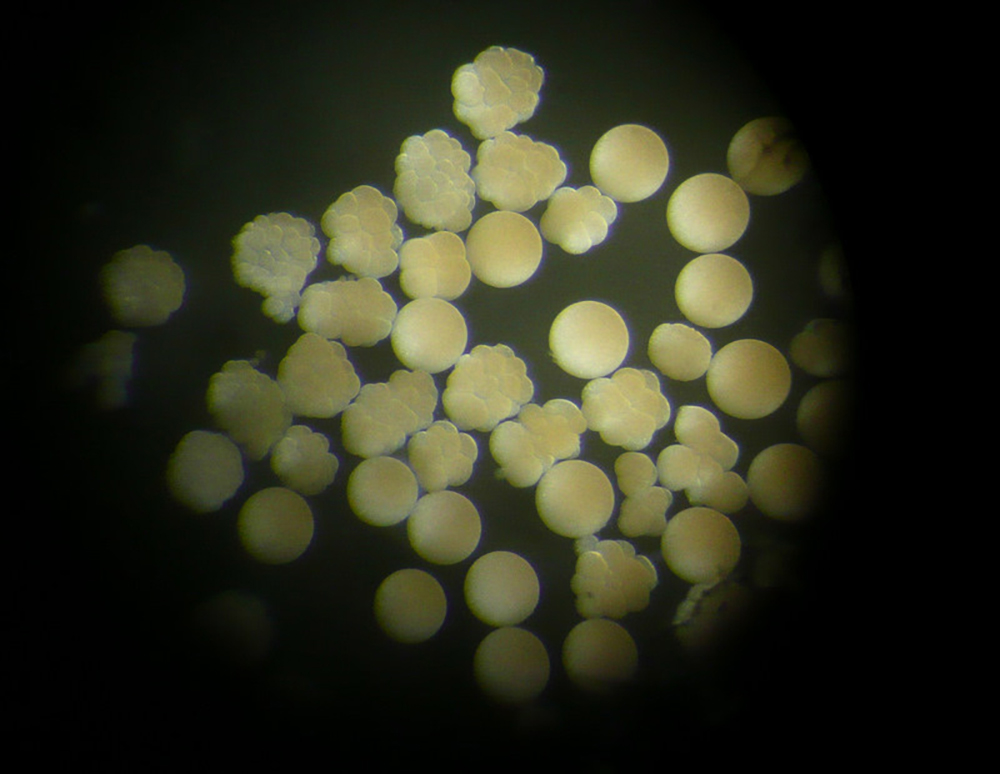

How it happens: Coral fertilization in action

Star coral eggs take almost two hours to start dividing after they’re fertilized, which sometimes feels like much longer! After 90 minutes of fertilization, we carefully move the embryos to filtered seawater to reduce the number of bacteria that can attack and kill them. We keep the embryos in dozens of plastic containers, each one holding about a liter of water. Every few minutes, we sample a small number of embryos and check them in a petri dish under the microscope. Finally, some of the eggs begin to pinch in half, forming two cells. It’s happening! The cells continue dividing in half over and over, each cell becoming tinier in the process. At this stage we can score fertilization rates for our cohort: the perfectly round cells are eggs that didn’t fertilize or failed to divide. In this image, fertilization is a little over 50%, not a great result but not terrible either. On nights when the fertilization rate is very high, we immediately send some of the embryos back to the ocean. We can’t keep them all alive in the lab, and we relish the chance to carry the “karma bin” out to the end of the pier. Photo: Kristen Marhaver.

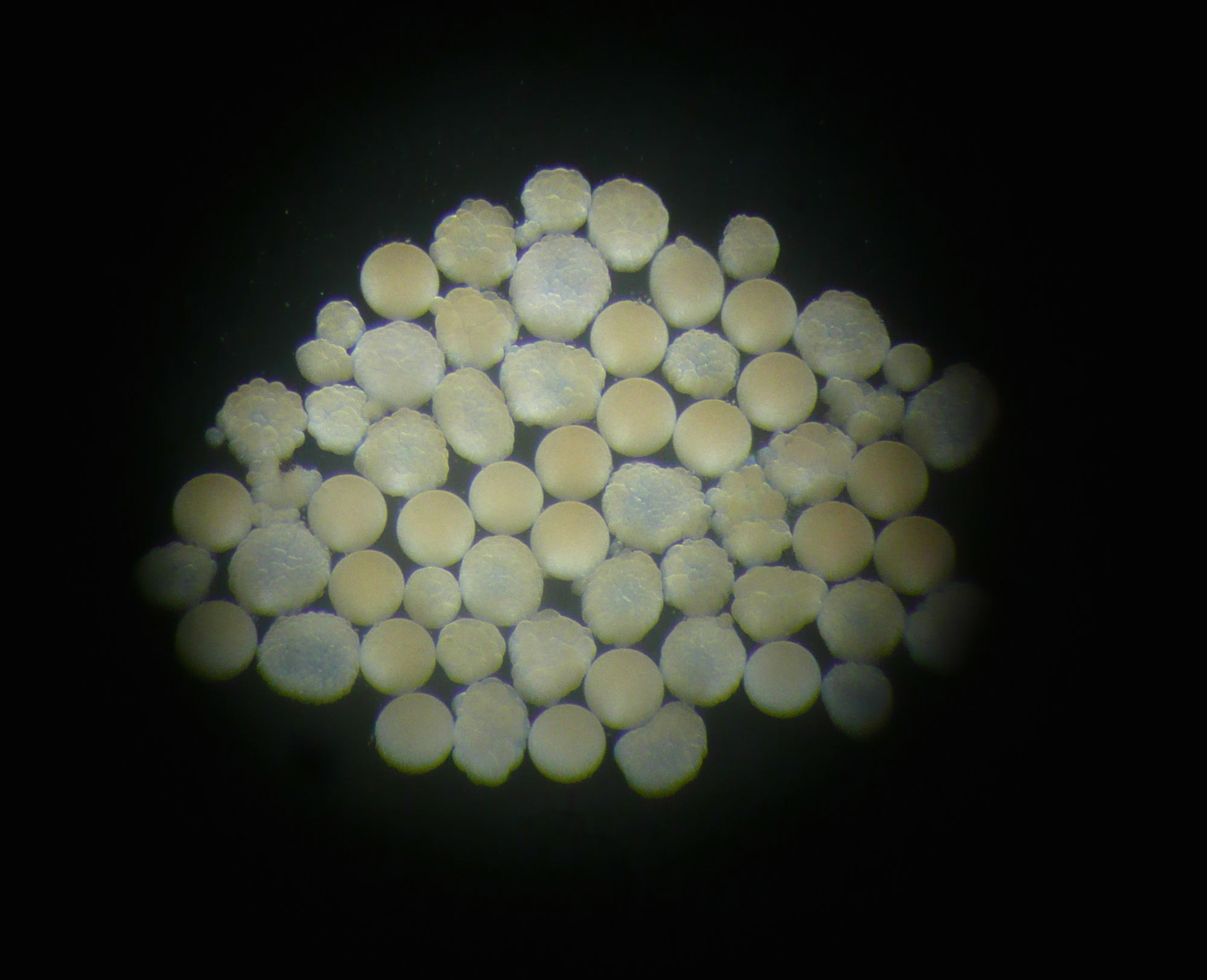

The magic of the blastocyst stage

The cells keep dividing until they form a hollow ball; this is the “blastocyst” stage that all animals — even humans — go through in their early development. Even though I’ve watched coral spawning for years, I still love staying up all night in the lab, watching this magic happen under the microscope. It’s still mind boggling to me that this is how corals are born. At this point in the night we can even FEEL the biology happening: the temperature in the lab goes up from all the biological activity going on. Those coral cells are copying all of their DNA every 40 minutes and rearranging their cellular material furiously, and they’re burning a lot of energy to do it! Photo: Kristen Marhaver.

Coral larvae — they grow up so fast

The next morning, the embryos have developed into larvae. At first, they are round and move only a bit from side to side, but then they grow up FAST. By the afternoon, they have truly learned to swim. The spheres have elongated into pear shapes like you see here, and they begin to swim across the water surface. They use small hairs called cilia to propel themselves in the water, and they’re pretty fast! We’ve measured them swimming a few millimeters — the equivalent of a few body lengths — in a second. Not bad for something so tiny. They need to be able to swim so that they can search a coral reef for exactly the perfect place to attach. Given that they usually spend their entire lives in that same place, this is a critical decision to make and these larvae have amazing sensory abilities to help them make the right call. As such, this is where we do the most research. We’ve studied how corals sense and react to different surfaces, sounds, light levels, colors, bacterial species, algae — even other coral species. It turns out coral larvae have very strong “opinions” about where they want to live. And human-induced threats like fertilizers, sewage, and temperature change all stress them out and reduce their ability to settle and survive. By studying their settlement choices and survival rates in lab experiments, we can help make sure the right settlement cues and habitats still exist for them out in nature. For some species, we can even return a few precious settlers to the reef to try to jumpstart the next generation. Photo: Kristen Marhaver.

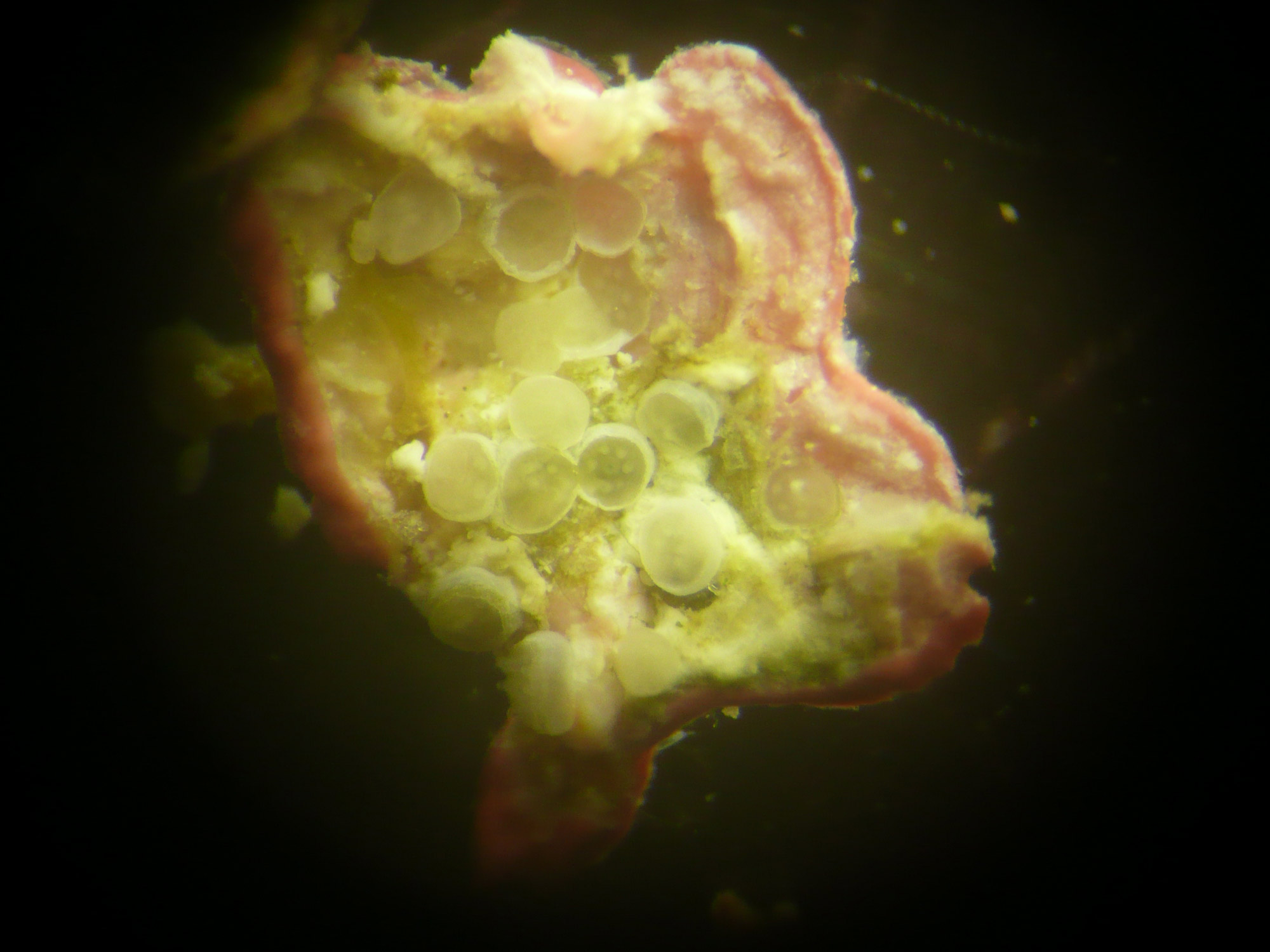

The star coral settle into their first homes

Here, about a dozen star coral larvae all chose to settle on the underside of a piece of pink coralline algae that we collected from the reef. The corals have now gone through the full settlement process including attachment, metamorphosis (growing their tentacles, mouth, and digestive system), and are beginning to grow their skeletons (the small white cups). They are still only 1-2 millimeters wide and very fragile. They often prefer to settle somewhere protected so they aren’t crushed by mobile animals like crabs. The delicate nature of the process, and the many ways human activity interrupts it, explain why coral settlement in the Caribbean is so much lower than it used to be. Photo: Kristen Marhaver.

Prime real estate — if you’re a star coral

Encouragingly, though, we’ve recently seen corals settle in some surprising places on a few reefs in Curaçao. For instance, a few new star coral colonies started their lives on a concrete block that sunk in a storm. The species only grows about a half an inch a year, so this colony is probably three or four years old. We’ve found that they really prefer vertical surfaces — perhaps because they seem to be safer places, with fewer animals walking around, and where there’s less sediment and sand piling up. From these tiny humble beginnings, a star coral can build a massive and impressive structure. Photo: Kristen Marhaver.

The beauty of a healthy coral reef metropolis

This is me diving on the north shore of Curaçao; the star coral here could be over 500 years old so even with my fins, I’m still not big enough to be the scale bar! Each coral colony tries to grow vertically toward the sun while it competes for space horizontally with other corals. You can see here how different colonies have grown up right next to one another. A healthy coral reef is like the center of a huge city — there’s almost no free space and competition for a place to live is fierce! Some of the reefs on Curaçao have suffered a lot in the past years, but the reefs furthest away from humans, and some of our luckiest reefs in town, still have some beautiful stands of coral. Photo: Mark Vermeij

We have some of the best remaining reefs in the Caribbean, but we won’t be able to keep them alive just by luck. Fortunately for the corals and the humans who depend on them, the government of Curaçao has started taking some bold steps to protect and nurture its coral reefs. What we learn in our research at CARMABI can be applied not only on the island but across the Caribbean, and even to other coral species in other oceans. By studying how corals reproduce, we can help give coral babies — the reefs of the future — their very best chance at surviving in our human world.