In 2004, Jason deCaires Taylor (TED Talk: An underwater art museum, teeming with life) was 29 years old and working as a scuba diving instructor in Grenada. He’d studied sculpture in college, but never quite mustered up the guts to attempt life as a full-time artist. His 30th birthday served as a swift kick in the pants. “I realized I didn’t want to do that the rest of my life,” said Taylor. “So I approached the government and my dive center, and talked to marine biologists about this idea of doing an underwater sculpture garden.”

And thus, Taylor began casting giant cement sculptures that weigh thousands of pounds — and sinking them into the ocean in areas with barren seabeds. The idea: to place whimsical objects underwater, where rays of light dance across them and algae, corals and other sea creatures can make them home. The final pieces are half sculpted by him, half crafted by the ocean; these eight projects from the past decade show off their unique underwater secrets.

The Lost Correspondent

In 2006, Taylor wanted to create a new tourist attraction in Molinere Bay. “Grenada’s got only one bay that’s good for snorkeling, so everybody goes to this one pristine place. The damage was bad,” he says. Taylor hoped that he could divert people with his underwater sculpture park, and this was the second piece he made for it. “My grandfather had just died. He was an avid letter writer. This piece was my last letter to him,” says Taylor. “But it was also just about how communications seem to be changing so rapidly.”

Vicissitudes

This sculpture from 2007 features a Grenadian boy and girl, repeated in a circle. The different castings of them have grown differently over time, based on their position in the current. “The piece is about how we’re all affected by our environment,” said Taylor. Assembling it underwater was quite a to-do. “I built it in the studio and it all fit together,” said Taylor. “But when we started to connect them up underwater, there was a slight gradient to the sand. We had to dig down to install the next one, and every time we’d dig, we’d find a rock. I spent ten days underwater trying to get it all together.” Taylor deliberately looks to install pieces in areas like this where the seabed is predominantly barren — just sand — but where currents would allow marine life to flourish. Each piece is anchored to the seabed to make sure it stays put during tropical storms and hurricanes.

The Bankers

“After the financial crash I was infuriated by the short-sightedness of what was happening,” said Taylor. “I wanted to use the banker as a symbol of how little we look to the future, and how everything is about short-term gain.” Taylor crafted a first figure with his head in the sand near Cancun, Mexico, in 2009. He added additional figures in 2012, each one in a “prayer position” to show that his “god had been replaced by monetary things.” Taylor confesses he sometimes voices his frustrations in hidden ways. “The Banker has an internal cavity between his buttocks for marine life to inhabit,” he says. “We had some crustaceans and eels living there. That was part of my revenge.”

Anthropocene

Taylor was thrilled to find about 100 lobsters living at the feet of one of his pieces in Cancun. “But a week later, every single lobster was gone,” he said. “They’d been taken out by fishermen in the night.” Taylor tried again in 2011 with this piece, a cast of a Volkswagen Beetle. “We wanted to create a lobster city that fishermen couldn’t get their hooks into,” he said. The sculpture is hollow, but it still weighed nine tons — which made getting it to its location a challenge. And for two years, no lobsters. “I thought, ‘Ah, it hasn’t worked,’” says Taylor. “But I went a year ago and it had 80 lobsters inside. I turned on my torch, and just saw thousands of feelers. It felt really good.” Note: the child crying on the windshield of this sculpture has nothing to do with the recent Volkswagen scandal. “The piece is about what we’re leaving to future generations,” says Taylor.

Inertia

The television in this 2011 sculpture in Cancun holds a surprise — it’s got tiny holes that provide refuge for young fish. The man on the couch, meanwhile, is surrounded by soda bottles, packs of cigarettes and other refuse associated with a sedentary lifestyle. “I bought a McDonald’s hamburger to cast,” said Taylor. “But I got it back to the studio and it looked so limp I sculpted the hamburger from scratch.”

The Silent Evolution

This piece from 2012, also in Cancun, contains 450 life-sized cement figures. “It’s a community of people, standing in defense of their oceans,” says Taylor. He cast about 90 real-life models to create the large-scale, man-made reef which is now home to more than 2,000 juvenile corals. “A lot of the people are replicated,” he said. “Because they change so dramatically underwater, I can have two figures from the same mold, and after a year they’re completely unrecognizable.” Taylor sources his models on the street and through the Internet, but for this piece he sought out local fisherman. The casting process takes 20 to 40 minutes — each person is slathered in Vaseline, then plaster. “I don’t think people realize at the time what it means. It’s only afterwards that they realize they’ve been immortalized,” he said. Many love it. “There’s one guy who has printed out his sculpture on t-shirts, and he does his own special guided tour.”

The Silent Evolution (at night)

Taylor uses pH-neutral cement for his works, a material he found thanks to the artificial reef building company Reef Ball. “They’d worked out that this pH-neutral cement was important for coral polyps to attach to,” says Taylor. “They’d also made it really durable so that it could sustain a coral reef.” The results are vibrant in the day, but even more so after the sun sets. “I love diving at night — the torch light illuminates all the true colors of the coral, sponges and algae,” he says. “Sometimes when there is a full moon, you can turn off all the lights and it is just beautiful.”

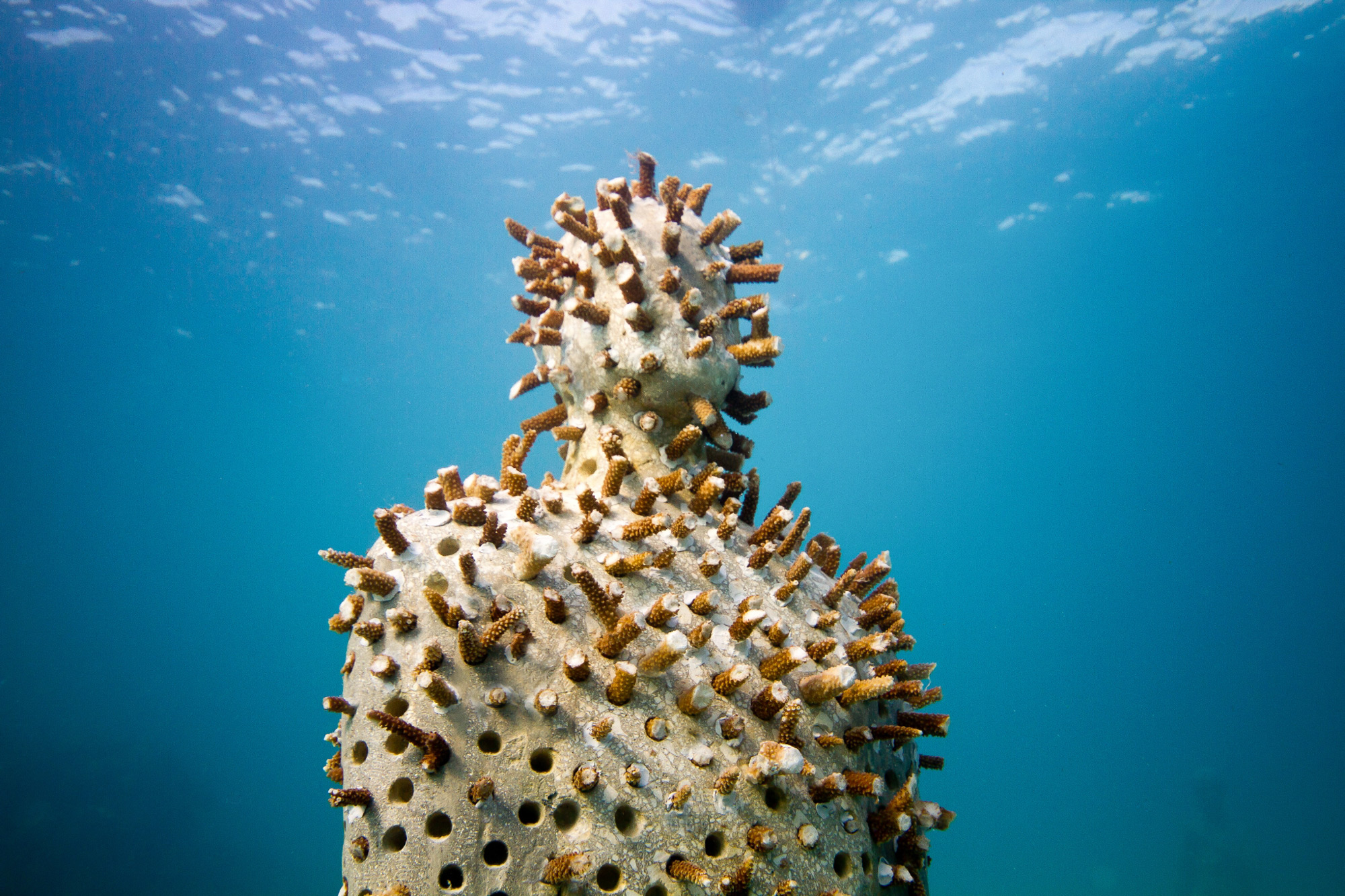

Holy Man

For this 2011 sculpture in Cancun, Taylor experimented by taking clippings of coral — just as you’d do with plants — and harvested them inside holes in the cement. “The coral interwove and created the silhouette — I just gave it a guideline of vague reference,” he says. “Some days, it’s incredible — all the fingers interlock, and you see this amazing shape with thousands of sardines swimming through. Other times, the coral might have an infection. It’s like with children — the coral goes through phases.”

Ocean Atlas

“The model here was a young Bahamian schoolgirl called Camilla,” said Taylor of this piece he created in The Bahamas in 2014. “She’s supporting the weight of the ocean on her shoulders, like Atlas.” This enormous piece weighed 60 tons when it was finished, and not many cranes can lift that kind of weight on water. “The crane’s on a barge. You have to counteract the weight with something on the other side of the boat to maintain stability,” he says. This piece took six weeks to create, which he admits was “intense.” As with all of his works, “Ocean Atlas” is designed to last. “The pieces won’t disintegrate. If anything, they will build up with more layers of calcium and growth. They will be transformed into something else,” he says. “I am making these inert objects, but the environment is giving them their souls.”