How a letter written in 1855 gave Kyra Gaunt a whole new perspective on slavery.

White Americans aren’t the only ones who don’t like to remember slavery and its history.

According to the Office of Minority Health, in 2012 there were 43.1 million people who identify as African-American. I could lay money that, next year, fewer than 1 percent will publicly celebrate the 150th anniversary of June 19th, or what we call “Juneteenth” — also known as Freedom Day and Emancipation Day — even though the holiday is recognized in 43 of our so-called United States. It was on this day in 1865 that, two years after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, the state of Texas freed the last enslaved Africans in America.

Many African-Americans don’t have detailed stories about our enslaved ancestors or their escape. At least, my family didn’t. When I grew up, no one in our community talked about enslaved people. They were objects in public debates, always referred to in some generalized manner. The talk was always “we come from slaves” (not enslaved African people).

We were property, not human beings whose culture and nationality was stripped with every stroke of a slavemaster’s whip. So I was struck to my core with tears when I recently read a copy of a letter written by my great-great-grandfather in 1855. He’d recently escaped slavery in Portsmouth, Virginia, on the Underground Railroad. When he reached Philadelphia, he sent this note to a friend, entreating him to help his (first) wife and children, who were in jail — left behind as a casualty of his emancipation.

Here is the letter, unedited and in full:

LETTER FROM SHERIDAN FORD, IN DISTRESS.

BOSTON, MASS., Feb. 15th, 1855.

No. 2, Change Avenue.

MY DEAR FRIEND:—Allow me to take the liberty of addressing you and at the same time appearing troublesomes you all friend, but subject is so very important that i can not but ask not in my name but in the name of the Lord and humanity to do something for my Poor Wife and children who lays in Norfolk Jail and have Been there for three month i Would open myself in that frank and hones manner. Which should convince you of my cencerity of Purpoest don’t shut your ears to the cry’s of the Widow and the orphant & i can but ask in the name of humanity and God for he knows the heart of all men. Please ask the friends humanity to do something for her and her two lettle ones i cant do any thing Place as i am for i have to lay low Please lay this before the churches of Philadelphaise beg them in name of the Lord to do something for him i love my freedom and if it would do her and her two children any good i mean to change with her but cant be done for she is Jail and you most no she suffer for the jail in the South are not like yours for any thing is good enough for negros the Slave hunters Says & may God interpose in behalf of the demonstrative Race of Africa Whom i claim desendent i am sorry to say that friendship is only a name here but i truss it is not so in Philada i would not have taken this liberty had i not considered you a friend for you treaty as such Please do all you can and Please ask the Anti Slavery friends to do all they can and God will Reward them for it i am shure for the earth is the Lords and the fullness there of as this note leaves me not very well but hope when it comes to hand it may find you and family enjoying all the Pleasure life Please answer this and Pardon me if the necessary sum can be required i will find out from my brotherinlaw i am with respectful consideration.

SHERIDAN W. FORD.

Yesterday is the fust time i have heard from home Sence i left and i have not got any thing yet i have a tear yet for my fellow man and it is in my eyes now for God knows it is tha truth i sue for your Pity and all and may God open their hearts to Pity a poor Woman and two children. The Sum is i believe 14 hundred Dollars Please write to day for me and see if the cant do something for humanity.

I wept deeply when I read this letter and an accompanying account of a merciless whipping before his escape. His writing spoke of options I never, even as a professor, realized an enslaved person could have.

Here was a literate man well versed in writing by 1855, who clearly articulates the value of his freedom, five years after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act from the Compromise of 1850 — which ended Reconstruction and led to the discriminatory, second-class-ranking Jim Crow laws. He could have been snatched back to Virginia if ever found in Boston by his lawful captors.

This is more than any memory passed down orally and better than any autobiography published in a book. It was evidence of a liberated truth. It was a local knowledge penned by a formerly enslaved man’s full grasp of a belief in God, in his humanity and in the justice of being newly free.

It seemed like a miracle to read the words of someone I am related to, someone I could trace to my bloodline instead of some generalized story about slavery. Reading the handwritten words of my grandfather’s grandfather changed something in me.

It turns out that we were more than anything I had ever learned — more literate, more compassionate, more enlightened — and contemporary youth must be remembered to this kind of inscribed evidence of our cultural evolution. Evidence of owning not just one’s liberty but one’s own literacy. I can now claim my descendence from the Race of Africa from the words of my own kin, from within my immediate family, and not from some televised fiction.

The cherry-picked popular slave narratives or mediated memories from Alex Haley’s miniseries Roots are like secondhand clothes, mediated scripts of third-world stories. They carry no local knowledge or memory at all: they are broken memories of forced migrations thrown overboard.

When we do get to the real memories, we try to tell “the right” story, the “grotesque” how-could-they-do-this-to-us story, or the capitalism-was-built-on-the-back-of-the-debt-paid-with-our-free-labor-and-forced-sex story. There’s Toni Morrison’s beloved story of a mother killing her children rather than let them live as chattel slaves. Non-Blacks aren’t the only ones who resist remembering slavery.

My great-great-grandfather lives first-hand: “i love my freedom.” We know enslaved people taught themselves to read and write. In this exchange of ideas written in 1855, Sheridan Ford speaks to not just valuing but owning his own freedom in ways no Hollywood script by Spielberg or Tarantino could ever aptly capture. Now I can’t wait to tell about his second wife, my great-great-grandmother Clarissa Davis, who escaped to freedom dressed as a man.

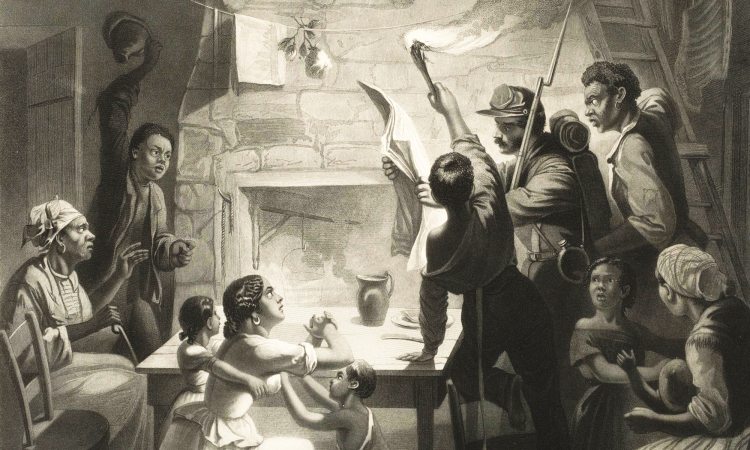

Photo: Library of Congress.