Climate change, coral bleaching, ocean acidification, overfishing … it can be easy to feel depressed about the ocean. But when you look at the big picture of ocean health, some good news emerges.

Marine conservation researcher Ben Halpern calls himself an “ocean optimist.” But getting there wasn’t easy — it’s taken more than eight years of research to reassure himself that maybe, just maybe, our seas are not doomed. How did he get there? By collecting and studying data from the oceans, and synthesizing billions of data points into maps that reveal previously untold stories in swirls of blue, green, orange and red. Here’s a look at some of the reasons Halpern sees hope beneath the waves.

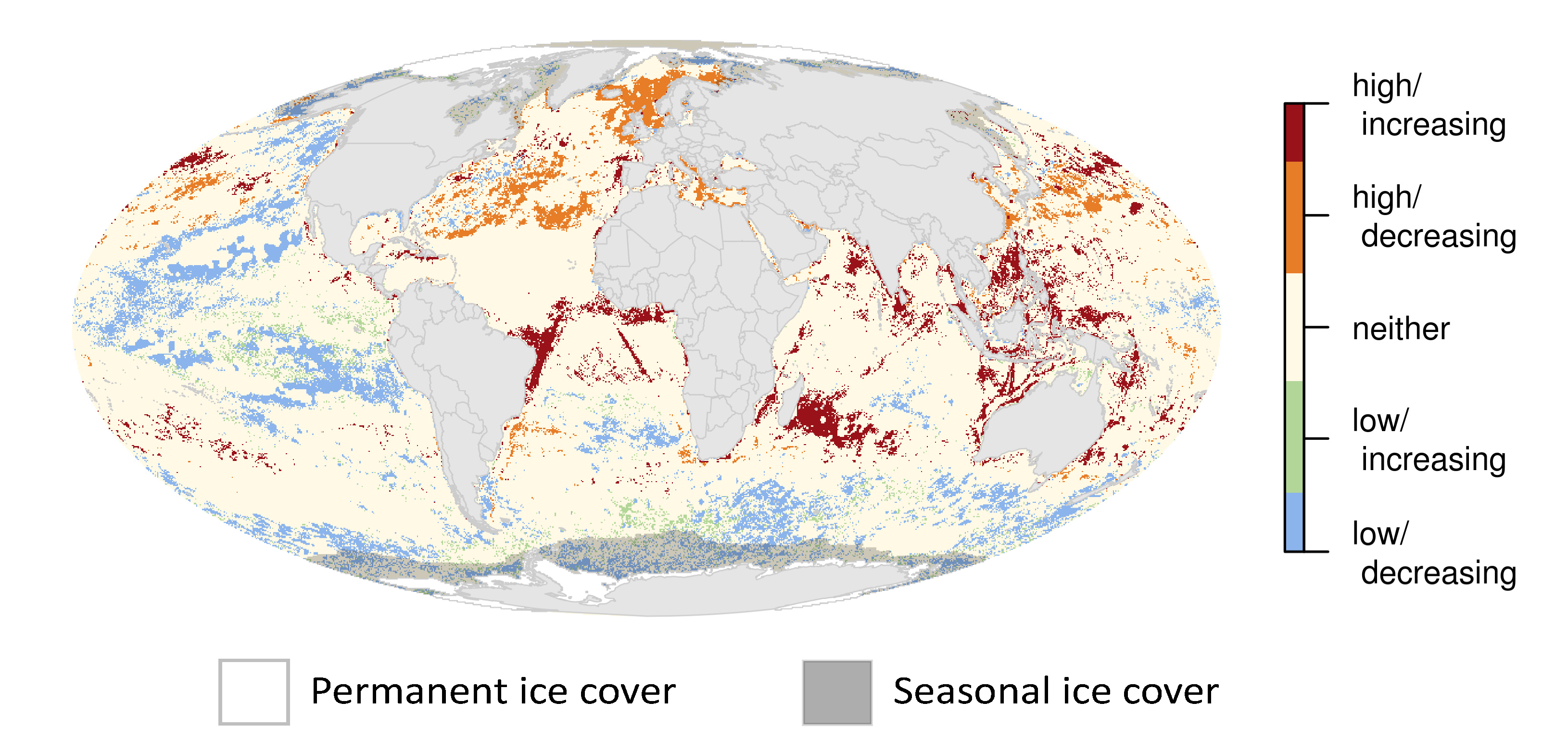

13% of oceans saw a decrease in human impact between 2008 and 2013. In 2008, Halpern and his colleagues at the University of California Santa Barbara’s National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis created a map to look at 17 ways that humans affect the ocean — from fishing to plastic pollution. Some dimensions had been mapped before, but no one had attempted to bring them all together cumulatively. “Mapping one thing at a time misses the big picture,” says Halpern. This new map gave that high-level vision — and provided a baseline to measure against. Last year, the team published a comparison in Nature Communications. While it probably won’t shock you that cumulative human impact got worse for two-thirds of the world’s oceans in the five years to 2013, 13% of them actually enjoyed less human impact. “That’s nearly 50 million square kilometers where things are getting better,” says Halpern. “These places give us hope that with concerted action, we can improve the state of the ocean.” He points to Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands as places where focused action influenced the big picture. While climate change and pollution increased there, strong regulation of commercial fishing offset the negative effects.

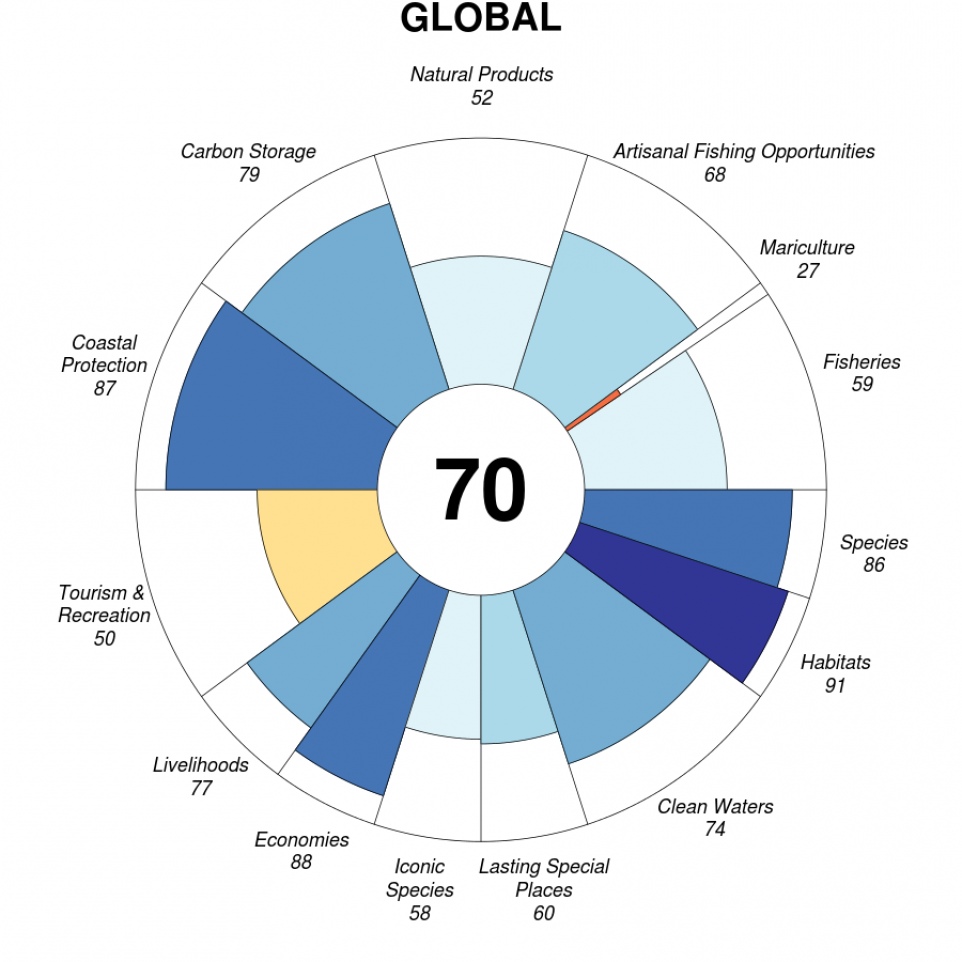

Ocean health improved 1% in the last three years. Halpern took the big-picture approach a step further with the Ocean Health Index, launched in 2012. Just as a fitness tracker monitors a person’s heart rate and steps, the index measures ten health goals for the ocean — such as providing ample food, supporting livelihoods and having thriving biodiversity. The index parses many different kinds of data and boils them down into a single ocean health score for the world, on a scale of 0 to 100. The world’s score for 2015: 70. Sure, that’s the equivalent of a C- in school — but in 2012 the world got a 69, meaning that ocean health ticked up one point within three years. “I wouldn’t run out into the streets and hold a ticker-tape parade,” says Halpern. “But we are hearing so many stories about the decline of the environment that any improvement is, in my mind, a big deal.” Many factors contributed to the improvement, such as a sharp uptick in the protection of marine areas, and coastal economies bouncing back from the global recession. Halpern also notes that in 2012, 20 countries received scores of under 50 — and all but nine had pulled themselves over that line in 2015. So why haven’t we heard about the improvement? “There’s real concern about the decline of the environment. Scientists and policy makers know we’re at a tipping point,” says Halpern. “I think there’s a fear that positive stories take the momentum away.”

Governments use ocean data to guide policy. The Ocean Health Index’s cumulative approach shows how specific actions can change the big picture. Mozambique, for example, received a poor score of 65 in 2012, in large part because of the dramatic effects of climate change there. In the years since, the government protected large marine areas and strategically increased the sustainable harvest of natural products like seashells; in 2015, Mozambique’s score nudged up 8 points to 73, above the global average. Sometimes, of course, action is a coincidence, but sometimes it’s a direct effect of the index. After Colombia got a low score of 52 in 2012, government ministers gathered to discuss how to do better. They worked with the Ocean Health Index team to prioritize actions and draw up what they called their “Agenda Azul.” The plan has had a measurable effect. In 2015, Colombia boosted its score to 61. More than 30 countries — including Ecuador, Israel and China — have now worked with the Index team to help them better assess the status and health of their marine resources.

Marine protected areas are a real thing now. In 2014, Barack Obama created 490,000 square miles of protected ocean around US islands in the Pacific — an area that’s about three times the landmass of California. In 2015, then-British Prime Minister David Cameron created the largest contiguous ocean reserve around the UK’s Pitcairn Islands in the southern Pacific — 322,000 square miles of ocean safe from seafloor mining and commercial fishing. “It’s like countries are competing to have the largest marine protected area in the world,” says Halpern, who points to a 2010 international agreement challenging countries to protect 17% of their land and 10% of their oceans by 2020. “Countries are realizing they’ve got to get going,” he says. Marine protected areas let species thrive and boost ocean resilience; the benefits come quickly and improve over time. “Species that have shorter life cycles and reproduce each year can respond within a year or two,” says Halpern. “It takes longer for species like big tuna, grouper or snapper to rebound. They live for decades, and don’t reproduce until much later. So even 15 years after creating the marine protected area, you’re still seeing increasing benefits.”

Aquaculture is also on the rise. Halpern predicts that one factor just starting to blip in the Ocean Health Index will have big impact down the road: the growth of aquaculture, or the farming of marine animals and plants. This practice will likely decrease the need for mass fishing, and it’s becoming a major industry in countries such as Chile, Norway, Thailand, Ecuador — and most notably China. “Aquaculture can be very sustainable,” says Halpern. “In the coming decade, we’ll see it take off and change the way that food from the sea is provided to people in a positive way. There’s a real set of opportunities here.” Right now, the world’s score for aquaculture is 27 — low, despite a 2% increase since 2012. But if it becomes more widespread, positive impact could influence other goals. “Shellfish aquaculture sequesters carbon,” says Halpern. “That’s a great source of protein with positive environmental impact. This is one part of the solution to addressing climate change.”

The Ocean Health Index has an optimistic idea at its core: that what’s good for the ocean can also be good for human beings. Restoring coastal habitats absorbs carbon while increasing safety for people who live there. Strengthening water regulations is good for aquatic animals and beach-goers. Protecting endangered species can boost coastal economies with tourism opportunities. “Ocean health is not just about pristine-ness,” says Halpern. “People are everywhere on the planet, interacting with the ocean. A healthy ocean requires those interactions to be sustainable. The momentum is already under way.”

Ben Halpern was one of 20 speakers aboard Mission Blue II, a TED conference focused on the oceans, organized with TED Prize winner Sylvia Earle. Watch talks from the event.