In journalist Mikhail Zygar’s innovative series, you can watch the events of that momentous year come to vibrant life on your phone in weekly episodes.

Imagine your phone screen getting hijacked by someone else’s — and it’s the phone belonging to astronaut Neil Armstrong. All of a sudden, you start receiving urgent texts from president Lyndon B. Johnson urging you to reach the moon ahead of Soviet astronaut Yuri Gagarin.

Sound alarming? Exciting? Now you can experience this scenario for yourself, thanks to Russian journalist Mikhail Zygar and his Future History Lab. They’re bringing the drama, transformation and turbulence of a pivotal year in world history to our phones with their mobile documentary series 1968.Digital.

The series tells stories of 1968 as if they happened on 21st-century social media and other apps. Designed to be seen on smartphone, the 40 episodes — each about 10 minutes long — explore 1968 via 40 key global personalities and events. (The series can be watched on a computer, too.) “I always wanted not just to bring the audience back to history but to take the historical figures and bring them to the present — to make them alive so they could be really communicating with us,” says Zygar, a journalist, author, filmmaker, TED Fellow and founder of Russia’s only independent TV channel, Dozhd. The series premiered in late April, and as of today, seven episodes are online in Russia, France, North America, the United Kingdom and Australia. (In the latter three, the series runs under the title “Future History 1968” and is distributed by BuzzFeed News.) A new episode will be uploaded each week until December 29.

Zygar chose social media as a storytelling device because it’s how people convey information now. “If I want my books to be read by American audiences, I translate them to English,” he says. “If I want to tell the story to contemporary audiences, I must translate it to contemporary language to engage those who wouldn’t otherwise care about history, but would love the format, the plots, the idea, the bold experiment.”

Before tackling 1968, Zygar first combined social media and history with the website Project1917. This project, launched in November 2016 to mark the centenary of the Russian Revolution, explored that year through the voices of well-known figures and ordinary citizens — drawing on hundreds of primary historical sources that Zygar found while researching his book The Empire Must Die: Russia’s Revolutionary Collapse 1900–1917. “I’d started reading the diaries of people who lived 100 years ago. As a journalist, I wanted to get acquainted with them, so I was ‘interviewing’ them via their diaries, their memoirs,” he says. “They sounded like they were written today, and they would be totally understandable for today’s audience — because all their problems are today’s problems. I decided to transform that information into a social media format.”

With the help of 20 editors, Zygar took more than 3,000 archival documents and turned them into a daily Facebook feed that unfolded over an entire year. “The idea was to show any user on any single day of 2017 what was happening exactly 100 years before,” he says. “So if the date was April 11, 2017, you’d see a Facebook feed for 11 April 1917, with quotes from various characters.” Besides sharing history in an engaging format, “we wanted to show that the Revolution was not made up of unknown, nameless and faceless Reds against Whites. They were real, ordinary people like us, who used the same language and who were trying to solve the problems of democracy or dictatorship. It’s as though they were discussing their problems next door, and we were there with them.”

After Project1917, Zygar was eager to tackle a topic of broader interest. “It was very important for me to address a more universal subject next,” he says. “While 1917 was an important era to cover for Russia, it was mostly of interest to Russian audiences. We wanted to use the abilities and techniques we’d developed to make an even more ambitious art project, covering a more globally relevant history.”

1968.Digital’s storytelling format puts the drama of history into the palm of people’s hand. In contrast to the daily updates on Project 1917, 1968.Digital builds episodes around key characters and the events surrounding them. The narrative unfolds solely through the communications tools and apps that have become part of our daily lives. “The main idea is to make the viewer feel that he’s involved, that he’s engaged with the drama that is being unveiled,” says Zygar.

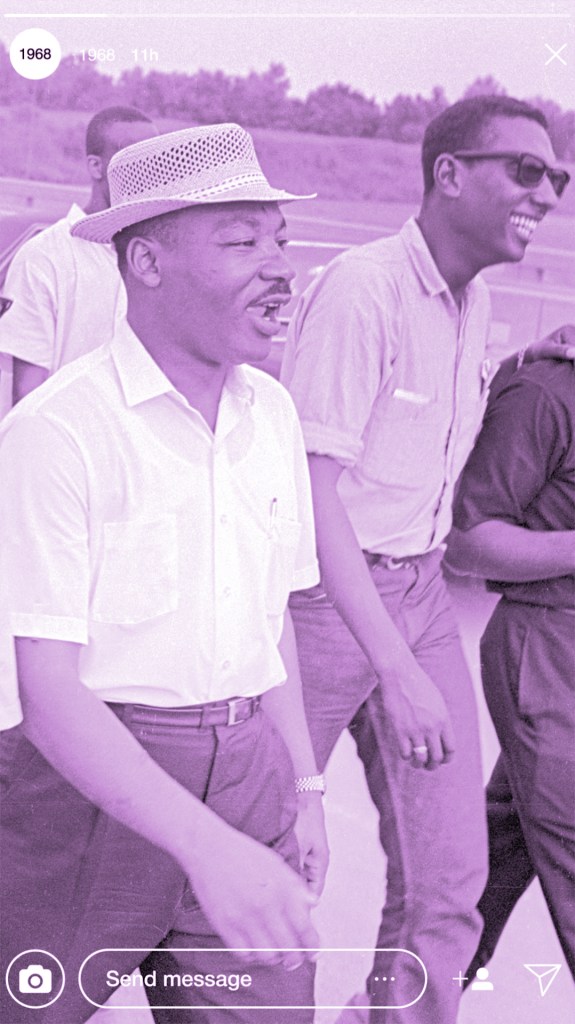

The result is an experience that’s as fast-moving and immersive as your daily social media activity. To create the documentaries, Zygar and his team — which includes Future History co-founder Karén Shainyan and producer Timur Bekmambetov, who came up with the “screen life” vertical format that scrolls like a newsfeed — gathered memoirs, interviews, documentary clips and archival footage and worked them into material for their characters to communicate via their iPhones. “We wanted to make it specifically to watch on a phone screen — not a desktop or TV,” says Zygar. “We’re following the characters through the lenses of their smartphones.” The 40 episodes will cover a wide swath of 1968’s political and cultural changes, spanning the US, the USSR, the UK, France, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Vietnam, China, Japan, Israel, Palestine, Mexico, Brazil and Cuba.

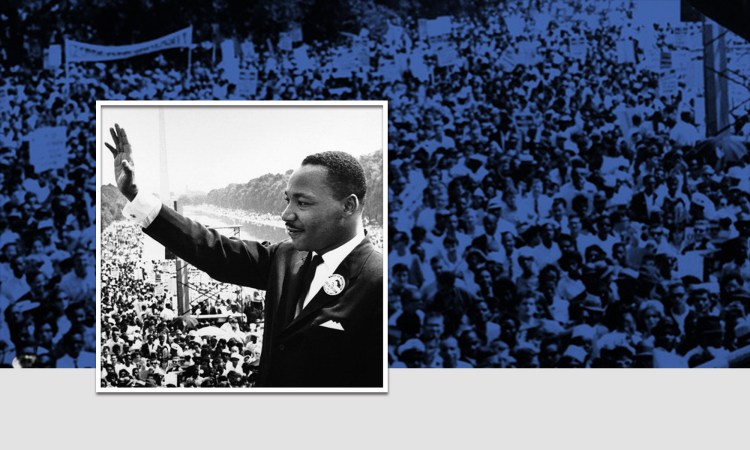

In creating the project, Zygar realized that every country had its own unique take and stereotypes about 1968. Americans, for example, might think about the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and RFK, the student protests against the Vietnam War, and civil-rights demonstrations. “Western Europeans remember 1968 as eventful for France, because of its student uprising,” says Zygar. “In Eastern Europe, most people would say the year was about the Prague Spring. In Russia, it was the year of the Soviet dissident movement. It was also the last year that the USSR was ideologically powerful, because after the Prague Spring, it lost popularity among European cultural elites. In China, 1968 is remembered as the peak of the Cultural Revolution.”

While Future 1968.Digital episodes delve into these specific political events, they also cover the cultural shifts taking place. “The most important things about 1968 were cultural — particularly the idea of human rights, which became a mainstream concept as a result of that year,” says Zygar. “It was also the most important year of the sexual revolution, of second-wave feminism and women’s rights.” Episodes are dedicated to feminist activist Betty Friedan, fashion icon Yves Saint Laurent, boxer Muhammed Ali and artist Andy Warhol, as well as to the rise of contraceptives and the sexual revolution.

Why should people care about 1968 today? The year is significant not only because we’re marking its 50-year anniversary. As far as Zygar is concerned, it was a moment of political and cultural upheaval that gave us the world as we now know it — so it bears mining for insight and connecting the dots. “History is just a rehearsal of what’s happening now,” says Zygar, who is busy completing the series and also creating The Russian History Map, a history-based game aimed at young people. “There’s a new Cold War; Black Lives Matter is similar to the 1968 campaign for civil rights; and #MeToo is the new wave of feminist protest.”

Our constant connectivity has accelerated some of the innovations that began back then. “In 1968, the first-ever propaganda TV program on Soviet television was established,” Zygar says. “It still exists, but back then, it was the only piece of Soviet propaganda. Those who are out to influence the public are more technologically advanced than they used to be, and the number of methods and leverages is much more diverse.”

By considering 1968 and how far we’ve since come — or not — we can get some long-term perspective on where we are and how we might proceed. “If we take history as a pretext, we can think more clearly about possible future scenarios,” says Zygar. “If we see we still have similar problems as we did 50 years ago, we must learn from the successes and failures of our predecessors.”