The past, present and future of food in space — from astronaut ice cream to “Enchilasagna” on Mars.

John Glenn was the first American to eat in space. Aboard Friendship 7 in 1962, he squeezed applesauce and puréed beef with vegetables from metal tubes down a straw and into his mouth through a port in his helmet.

The world was captivated. This strange method of consumption was so intriguing that, while tubed, puréed food was quickly abandoned, it continues to be what most people think astronauts eat.

Today, space food has come a long way. It’s no longer about astronauts simply meeting a calorie requirement while on short trips to the moon; it’s about them living semi-comfortably in space over months. Below, an overview of what’s changed since the 1960s — and what’s happening next.

The past

Yes, tubed food was a hit with America at large. But not so much with the people who actually had to eat it. By the Gemini and Apollo missions of the mid-1960s, dehydrated, freeze-dried and bite-sized foods were the trend, to cut down on equipment-damaging floating crumbs while providing a more human experience of eating.

“Space food became a kind of modernist symbol of the times to come,” says TED Senior Fellow Angelo Vermeulen, who recently led a four-month NASA study simulating cooking and eating on Mars. “It’s this idea of, ‘We’re going to change the future technologically.’ It became a strong symbol of the belief in progress in the ’50s and ’60s.”

Astronaut ice cream made a single flight into space.

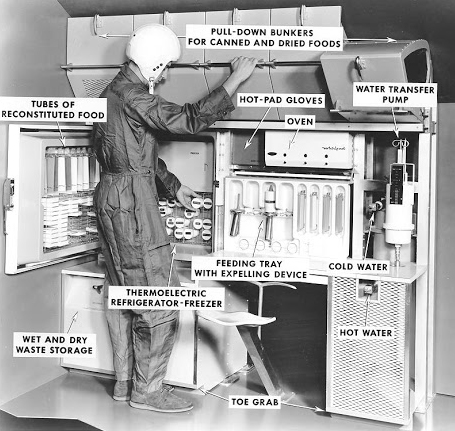

Many foods of this era were created with the help of the same people who made washers and dryers. Whirlpool Corporation debuted its Space Kitchen at a convention in 1961; with a refrigerator, freezer, water system and disposal units, all packed into a 10 x 7.5-foot cylinder, it was designed to take care of all the food and beverages needs for a 14-day mission. Between 1957 and 1973, Whirlpool completed 300 space-related kitchen contracts, and employed 60 people to design, develop and package food for space.

One famous food the company created: astronaut ice cream. But while it’s a perennial best-seller at your local science museum gift shop, freeze-dried ice cream only made a single flight into space, in 1968 aboard Apollo 7.

“Space ice cream was a special request for one of the Apollo missions,” Vickie Kloeris, manager of NASA’s Food Tasting Lab, told educators. “It wasn’t that popular; most of the crew didn’t like it.” After taking one bite (which this author did, for science), it’s easy to see why it was abandoned. It tastes vaguely like sweetened styrofoam. But the marvel lingers as kitsch.

“Space ice cream was a special request for one of the Apollo missions,” Vickie Kloeris, manager of NASA’s Food Tasting Lab, told educators. “It wasn’t that popular; most of the crew didn’t like it.” After taking one bite (which this author did, for science), it’s easy to see why it was abandoned. It tastes vaguely like sweetened styrofoam. But the marvel lingers as kitsch.

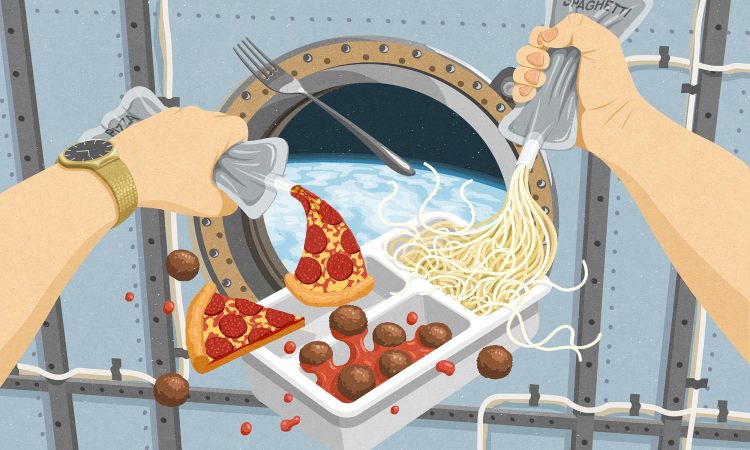

Since the early days of food in space, many other foods have been attempted and failed. Wine is a challenge, because it’s fermented and not sterile for space. Soda is stubborn too, because carbonation acts very weird in zero gravity. But one big innovation has come in the way astronauts eat. In space, your meal might float off before you’ve had a chance to eat it. The solution that developed over time? Food items are velcroed to a tray, which can then be attached to a table.

The table itself was an astronaut demand. “The original Space Station took out the table because nothing stays on it anyway,” says Mary Roach, author of Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void. (Watch her [unrelated] TED Talk, “10 things you didn’t know about orgasm.”) “But at a certain point, the astronauts said, ‘Bring back the table. Put some straps on it. We want to sit around a table at the end of the day and eat like humans.’”

The present

Human beings live aboard the International Space Station for as long as six months at a time. “Food is absolutely crucial to the psychology of your crew, and you need to handle that carefully,” says Vermeulen.

according to NASA, flour tortillas are the new bread.

Today, astronauts order off a menu — one far, far more extensive than what you’d find in a restaurant. According to NASA, astronauts are given more than 200 food and beverage choices to select from, most of them developed at the Johnson Space Center’s Space Food Systems Laboratory in Houston. About 8 to 9 months before launch, astronauts join a food evaluation session where they sample foods and pick breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks, from scrambled eggs to macaroni and cheese. Foods are tuned to give astronauts the nutrition they’ll need. While they need to consume about the same number of calories as they do on Earth, the amount of iron in their diet is limited to 10 milligrams per day. Sodium is also limited, to maintain healthy bones.

Some of the foods astronauts eat are dehydrated, to save on space and weight. These foods typically come in snippable packages, so water generated by shuttle fuel cells can be added. Other foods, like fruits, fish and meat, are thermostabilized or irradiated to kill micro-organisms and enzymes. And still other foods, like nuts and baked goods, are fine just as they are.

Salt and pepper come in liquid form. Coffee and juices come as powder. And according to NASA, flour tortillas are the new bread. “Tortillas provide an easy and acceptable solution to the breadcrumb and microgravity-handling problem,” their materials read — a theory Chris Hadfield (watch his TED Talk, “What I learned going blind in space”) confirmed in this video that showed how to make a sandwich in space.

Fresh foods, like vegetables, are available upon launch and via special delivery — but they don’t last long, and they have to travel far. And there is risk: On October 28, 2014, an unmanned resupply rocket headed for the International Space Station exploded seconds after liftoff. Onboard were 1,600 pounds of scientific equipment … and 1,360 pounds of food.

For ISS crewmembers, their menu repeats every eight days. On holidays, they can request special items that remind them of home. They also get “psychological support kits” from friends and family that can contain special treats. But having an assortment of foods isn’t necessarily enough to ward off food fatigue. The problem with space foods is that they don’t quite taste like the Earth version — “they’re either blander or there’s a weird flavor,” Roach says. “It’s highly processed, pasteurized and tweaked a million ways to deal with the packaging and the safety and the shelf life.”

And there are physical issues too. “One thing that happens in areas of microgravity is that you have more fluid in the upper part of your body, so in the first few days you’re a little congested,” she says. “You’re not smelling things as well. Food might not be as appetizing as it otherwise would be.”

Astronauts fight back against this … with sauce. “Some of them bring their own condiment bottles. They’ll bring pesto,” says Roach. “I’ve heard a lot of hot sauce gets used.”

What are the foods the astronauts love? According to Roach, shrimp cocktail rates very highly. “It was the most popular item for a long time because it held up really well. The flavor of the frozen shrimp and the cocktail sauce didn’t change much,” she says. “There was one astronaut who went through his menu for breakfast, lunch and dinner for all of them: shrimp cocktail, shrimp cocktail, shrimp cocktail.”

But NASA is always upping its foodie game. “The birth of the Food Network and all of the mainstream cooking shows has trickled down,” says Roach. “A number of celebrity chefs have stepped up to design and create recipes for NASA.” Space foods are also being developed that reflect “the diversity of the crews up there,” she says. One example? Space kimchi.

But mission lengths are still expanding, and the effects on the body are yet unknown. For this reason, twin astronauts Scott and Mark Kelly have volunteered for a year-long mission — Scott up at the ISS, Mark here on Earth — starting next March, to test and compare how the space-bound twin is affected by a long stay. (Watch Mark’s unrelated TED Talk with wife Gabrielle Giffords, “Be passionate. Be courageous. Be your best.”) Posting one twin to space and keeping one on Earth stands to teach NASA a lot about the effects of space on the human body. Still, on that 365-day mission, an eight-day rotation of food might start to feel pretty boring.

The future

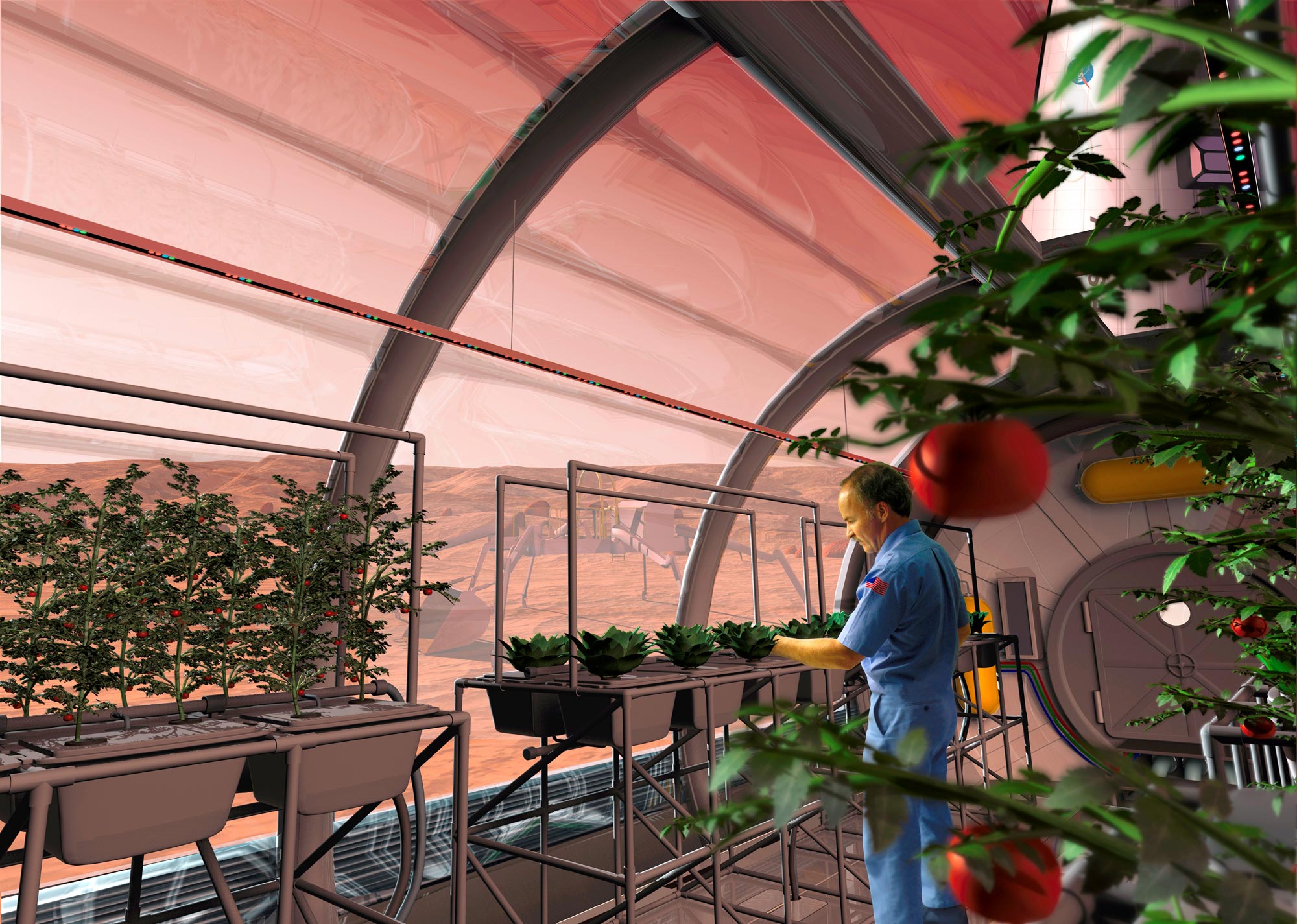

And this brings us to the next phase: figuring out food systems that could feed astronauts on missions lasting years. This means that NASA’s current standard for shelf life — 18 months — will no longer cut it. Up to five years will be more like it. According to NASA materials, the agency imagines astronauts eventually building “hydroponic growth labs,” where they will grow vegetables, potatoes, soybeans, wheat, rice and beans.

With missions lasting years, the issue of menu fatigue escalates to a serious problem. “One of the solutions is to allow the crew to cook,” says Vermeulen. “Cooking empowers you over your food. You can make endless variations, and there’s a bonus: it improves social cohesion. You talk about food, you share food. It’s a basic human thing.”

Someday, hydroponic growth labs could allow astronauts to grow vegetables, soybeans and rice.

Space agencies haven’t yet explored this avenue in practice for a few key reasons: Cooking requires water and energy — two things that are extremely precious in space. It also requires time — and astronauts lead very busy lives completing their orders. Finally humans in space are currently in microgravity, where cooking isn’t really possible.

But Mars has gravity, about 38% of Earth’s.

In 2013, Vermeulen was a part of the NASA-funded Hawaii Space Exploration Analog & Simulation — otherwise known as HI-SEAS. He participated in a four-month study to test the feasibility of astronauts cooking their own food. “The main goal of our study was to see if we could develop a different sort of food system,” he says. “The premise was: if you allow astronauts to cook their own food once they’re on a planetary surface or on the moon, then they might regain their original appetite.”

The rules of this study: the six crew members could only cook on anointed days. They could only use limited energy between their hotplates, oven and water boiler. All the food they had at their disposal was shelf-stable — flour, rice, sugar honey, and freeze-dried ingredients — important, as it saves on the mass and energy needed for refrigeration.

“We all preferred the days when we were allowed to cook. Those meals were just better,” says Vermeulen. “During our mission we always cooked with two people, and this had an interesting psychological benefit. When people are in the kitchen cooking, they are also talking. It’s a good way to keep the communication lines open. It’s also a really good outlet for creativity — something you really crave for when you’re locked up in a small space. And then when the food is served, you’re actually proud of what you made and you’re serving it to your colleagues. It generates more social cohesion,” says Vermeulen. “The disadvantage is that it does take a little more effort and time. So it’s a trade-off. Do you want your crew to be super-efficient and just heat something up in a couple of seconds and then continue working, but over the long term suffer from psychological consequences? Or do you give the crew time to make sure that the appreciation of food and the social and psychological benefits are maximized? I think for a future long-term stay on a surface, it’s probably going to be a combination of both. Some days you’ll just want to keep working, and then other days you’ll really enjoy having an original meal.”

Vermeulen says that the mission brought a lot of surprise. For one, that freeze-dried vegetables are actually good. “There are two ways to turn vegetable into a shelf-stable ingredient — dehydration and freeze drying,” he says. “When you rehydrate dehydrated vegetables, they’re chewy — they don’t have that crispiness and they turn a little brownish. With freeze drying, you take the vegetable and it doesn’t weigh anything at all. It’s super light. You put it in water, you see a sizzle and it pops back to life. The vegetables retain much of their original texture and color. It’s quite nice to have fresh, green stuff on your plate.”

Egg crystals were also a surprisingly successful ingredient. “It looks like yellow sugar — you mix it with water and you get the same substance as a few raw eggs scrambled,” he says. “That can be applied to so many things. Even making a simple omelet in the morning can make such a big psychological difference.”

The crew in the study was highly multicultural, and Vermeulen says that he noticed a few cultural differences in terms of foods people wanted to cook. They enjoyed Latino food, Russian food, American food. “My North American crewmembers would tend for things like shelf-stable bacon,” he says. “Personally, I’m not a big fan of bacon, but for some of my American crew members, it was a big moment.”

He did feel that kind of excitement for bread, though. “It was always a joy to have fresh bread, to have the smell of the bread going through the habitat,” he says. “You take a bread machine — it’s not that heavy. All the ingredients for it are all shelf-stable, so you can bake bread for years.”

The crew was also quite mixed in terms of cooking ability. Vermeulen says that while he’s at a medium level, some of his crew members were cooking novices, while three were notably excellent cooks. “Having six genius cooks doesn’t represent the typical astronaut crew,” he says.

Once a meal was prepared, each member of the crew passed by a station and weighed and photographed every single item of food. The crew members evaluated the food before they ate it and then evaluated it again after eating. Then at the end of the day, the cooks would write a report giving an overview of the recipes. This data is now at Cornell University being analyzed.

Anecdotally, the most popular foods made during the study: mashed potatoes (from flakes and granules) and the assortment of soups, from seafood chowder to Russian borscht. Apple pancakes were also popular. “We had dehydrated apple slices and then we could make our own pancake batter, adding white sugar and lemon juice,” he says. “Oh my god. I could have it now – it’s perfect. You could do that on Mars, as it’s all shelf-stable.”

The least popular dish: Kung Fu Chicken. “Whenever we had that, everyone would be like, ‘Oh no, another can,’” says Vermeulen. “But you’re so hungry that at least you eat some of it.”

Allowing astronauts to cook is really about giving them autonomy.

Experiments happened too. For example, the crew created “Enchilasagna,” enchiladas meets lasagna.

Allowing astronauts to cook is really about giving them autonomy, says Vermeulen. “Autonomy is a big item for the future of space exploration,” he says. “At this point, astronauts are almost constantly in contact with mission control — they have to carry out protocols, and their daily schedule is broken down into like five-minute segments. We won’t be able to retain this … because of the communication delay. Giving people autonomy is highly motivational. If you want to keep people sane on a three-year trip to Mars, you [can’t] control every single minute of their lives.”

Roach imagines technology advancing to the point where living on Mars isn’t so different from living on Earth. “For a Mars mission, if they were to have a rotating habitat where there was gravity, you could actually put food on the plate and eat it with a fork and not have to deal with making the consistency goopy enough where it’s not going to leave the spoon,” she says. “I think that would be a huge benefit.”

In space, what people want is comfort food.

But neither Roach nor Vermeulen think that there will be restaurants to choose from there. Vermeulen imagines a community more like ones in the polar regions, tiny settlements geared toward functionality rather than aesthetic pleasure. At best, they’ll have a canteen, he thinks.

Roach agrees that the pinacle will be a quiet victory. “With space food, the future is unlike what you might think. It’s not moving toward a more high-tech situation — it would be moving toward a more low-tech, more familiar and human situation. That’s really the holy grail with space food. What people want, ironically enough, is comfort food.”

Featured illustration by John Holcroft for TED.