Historically, science has been a male-dominated field. Despite dramatic increases in representation over the last 40 years, globally fewer than 30 percent of researchers today in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) careers are women.

Women scientists are also paid less for entry level jobs; they tend to have shorter careers with less progression and growth; and only make up about 25 percent of scientific paper authors despite publishing an equal number as their male counterparts. (It’s even less in fields like math, physics and computer science, where women authorship is 15 percent).

Yet in the face of enormous challenges, numerous women have fought their way to the fore and flourished. Here are eight lesser-known women scientists who defied the norm, excelled and made lasting impacts in their fields and beyond.

Eunice Foote, American scientist (1819-1888)

The greenhouse effect — the gradual warming of Earth’s atmosphere — is one of the foundational discoveries of climate science that is often credited to British scientist John Tyndall. But it was actually the pioneering scientist and women’s rights activist Eunice Foote who first theorized and demonstrated the greenhouse effect.

In the 1850s, she performed a series of experiments, where she filled glass cylinders with different gases, placed them in the sun, and measured temperature changes. Her findings demonstrated that the sun’s rays are warmer when passing through moist air compared to dry air — and they are warmest when shining through carbon dioxide.

In 1857, she published her groundbreaking findings in the American Journal of Science, but was largely overlooked (she even had to ask a male colleague to present her findings at a scientific conference because she was not allowed). Despite publishing her results three years before Tyndall, he was credited with discovering the greenhouse effect until recently. Today, climate scientists seeking to right past wrongs are pushing to give Foote her due credit and recognition for her early discoveries.

Lise Meitner, Austrian & Swedish physicist (1878-1968)

The discovery of nuclear fission — the ability to split atoms — changed nuclear physics and the world, laying the foundation for the development of the atomic bomb and nuclear reactors. We have physicist Lise Meitner to thank for it. She suggested her chemist colleagues, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman, try bombarding uranium atoms with neutrons in order to learn more about uranium decay. But being a Jewish woman living in Berlin in 1938, she was abruptly forced to flee to Stockholm to avoid persecution by the Nazis, and left her research behind. While she was in forced exile, Hahn and Strassman began to get some unexpected and hard-to-explain results. She partnered with Austrian-born British physicist Otto Frisch, who was also in Sweden at the time, and the duo named and described what Hanh and Strassman uncovered: fission.

Despite her involvement, the men surrounding Meitner were credited with the discovery. When a Nobel Prize was awarded to Hahn for “his discovery of the fission of heavy nuclei” in 1945, Meitner was never mentioned. She was nominated 48 times for Physics and Chemistry Nobel Prizes but never won. In 1966, Meitner was finally recognized for her contributions to nuclear fission when the US awarded her the Enrico Fermi Award alongside Hahn and Strassman. She passed away two years later.

Alice Ball, American chemist (1892-1916)

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s Disease, is a devastating, highly stigmatized bacterial infection that has plagued humankind for eons—the earliest mention of a leprosy-like disease comes from an Egyptian papyrus dating to around 1550 B.C. Traditionally, one of the most common methods for treating contagious patients was no treatment at all — they were often taken to isolated locations where they would suffer and eventually die in isolation. Oil from the chaulmoogra tree, a traditional Chinese and Indian medicine, was known to alleviate symptoms, but it was difficult to apply and couldn’t be injected because the oil didn’t mix with blood.

In 1916, African American chemist Alice Ball discovered a breakthrough in treatment. Twenty-three-year-old Ball, the first woman and the first Black chemistry professor at the University of Hawaii, discovered how to transform chaulmoogra oil into fatty acids and ethyl esters that would make the medicine injectable. Months after her faculty appointment and discovery, Ball died from complications related to a lab accident. The head of her department, Arthur Dean, continued her work and published Ball’s chemical process under the name “Dean’s method” after himself. Fortunately, one of Ball’s colleagues spoke up and helped change the name to “Ball’s method.”

Bessie Blount, American nurse, inventor and handwriting expert (1914-2009)

As a child, Bessie Blount was once reprimanded by her schoolteacher for being left-handed. So naturally, she learned how to write with both hands as well as with her mouth and toes. After becoming a nurse and accredited physiotherapist, she used her unique skill set to help young amputees returning from WWII learn new ways of accomplishing daily tasks.

She went on to invent devices that made everyday activities easier for veterans with disabilities, including a self-feeding apparatus for amputees. She shared it with the American Veteran’s Association and was the first Black woman to appear on the “The Big Idea,” a TV show about modern inventions, in 1953 — but had trouble garnering support. She eventually donated the patent for the self-feeding apparatus to the French government so people could freely benefit from the invention. Some of her later health-oriented inventions, like the vomit basin, are still in hospitals today.

A true Renaissance woman, at the age of 55 Blount became the first Black woman to train with Scotland Yard as a handwriting expert and went on to make a career as a forgery expert. After retirement, she started a consulting business for museums and researchers to examine the authenticity of antebellum letters and documents.

Katherine Johnson, American mathematician (1918-2020)

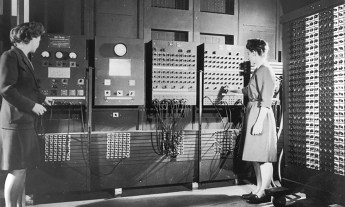

Thanks in large part to the 2016 book and movie “Hidden Figures,” Katherine Johnson, a NASA research mathematician (who were once called “human computers”), has emerged from obscurity. She began working in the NASA West Area Computing Unit in Hampton, Virginia, in 1958, and had to overcome stereotypes and adversity as a Black woman in a field dominated by white men at a time when NASA, and much of America, was still racially segregated.

She confirmed the trajectory analysis that took Alan Shepard, the first American to travel into space; verified the calculations that plotted John Glenn’s orbit around Earth; and helped to hire and promote women in NASA careers. But, likely due to the fact that she was Black and a woman, it took years for her to get the proper recognition for her work. Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015, and when she died in 2020 at the age of 101, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine called her “an American hero.” In February 2021, NASA’s Washington DC headquarters were named in her honor.

Rosalind Franklin, British chemist (1920-1958)

In school, children learn that the double helix structure was discovered by Watson and Crick, but it was crystallography expert Rosalind Franklin who took the game-changing x-ray “Photo 51” of DNA in 1952. Taking the photo itself was a huge challenge, but it took Franklin another year to fully interpret and describe the double helix structure we know today.

This is where accounts deviate. Watson and Crick, who were simultaneously trying to map the structure, came to a similar conclusion — possibly by sneaking a peek at Franklin’s Photo 51. They ran a quick analysis, made their best guess at the structure and published their findings at the same time as Franklin. The problem? Franklin’s work appeared in the same journal in the pages behind Watson and Crick’s paper, leading people to assume that her work supported their research. Tragically, she died of cancer before the papers were published and never knew about her competition.

Her work on DNA was far from her only success. For her PhD thesis in chemistry at Cambridge, she unraveled the structure and porosity of coal, which helped the British develop better gas masks during WWII. Her later work on RNA and viruses also supported chemist Aaron Klug’s work creating 3D images of viruses, which received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1982.

Elinor Ostrom, American economist (1933-2012)

For a long time, it was assumed that humans weren’t great at sharing. According to the “tragedy of the commons” theory, when individuals have unregulated access to resources — fresh water, forests, fisheries — they will act in their own self-interest and deplete those resources, even if it’s bad for the whole group. Then came economist Elinor Ostrom. She documented communities around the world that effectively and sustainably managed their shared natural resources by organizing at the local level. Based on this research, she proposed that local and regional organization is paramount to tackling the climate crisis and cautioned against relying heavily on global policy as a solution.

She became the first woman laureate to receive the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009, following in the footsteps of 62 male laureates (her cowier was the 63rd). Thanks in part to Ostrom’s work, community-based resource management has flourished and is credited with empowering rural development, reviving declining species and building resiliency against the impacts of climate change.

Carolina Vera, Argentinian meteorologist (1962- )

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, was founded in 1988 and remains one of the most authoritative global sources on climate science and plays a key role in global policy. But when it comes to authorship within the IPCC, women are underrepresented — and the barriers are even greater for women of color and for those from the developing countries.

“This bias could challenge the representativeness, legitimacy, and content of the reports if they fail to adequately incorporate the scientific expertise of developing countries, indigenous knowledge, a diversity of disciplines in natural and social sciences, and the voice of women,” according to a recent study on women scientists in the IPCC.

That’s what makes Argentinian meteorologist and climate scientist Carolina Vera an important voice for underrepresented groups. Vera serves as Vice Chair of Working Group 1 of the IPCC. Her research focuses on climate variability and simulation — from monsoons to rainfall and heatwaves — and how these models can inform our capacity for climate resilience. Despite the challenges of being a female scientist in South America (a male professor reportedly once told her, “I don’t want you to contradict me in public”), Vera continues to pave the way for other female climate scientists.

Watch Rachel Ignotofsky’s TEDxKCWomen Talk on women in science now: