British lawyer Alexander McLean’s fascination with issues of inequality began at a young age. At 9, he was reading about the Civil Rights movement and the death penalty, fascinated by the power of the law to inflict punishment as well as deal out justice. At 18, he traveled to Uganda to volunteer as a hospice worker, where he saw that while patients with private resources received care, inmates sent from prisons were left neglected and untreated. His hope to do something about this disparity has over the years evolved into The African Prisons Project, helping prisoners in Uganda and Kenya access a legal education, and working to develop leaders among prisoners and prison staff. We spoke to the TED Fellow to find out more about how the project came to be — and his hopes for its future. An edited version of our conversation follows.

How did you get involved in working in Africa?

I used to volunteer at a hospice in London every Sunday, where I would spend the afternoon on the wards with patients and their families. In my first few weeks there, I met a teenage girl who was dying of brain cancer. Her whole head was wrapped in bandages, and she couldn’t move. Seeing so many people dying in hospice got me thinking that life isn’t guaranteed. We can’t put off any dreams. The experience got me interested in palliative care, so when I read about Hospice Africa Uganda, I decided to ask if I could visit.

The porter came with a trolley with a dead woman. he put his body on top of hers, and said they’d go to a mass grave together.

You were only 18 years old when you first visited Kampala. Yet it seems like it had a profound effect on what you did next. Tell us about the trip.

It was humbling. One day we went to Uganda’s main government hospital, where I cared for prisoners and abandoned patients. In Uganda, nurses almost never wash patients, feed them and so on. That’s family work. Only patients who have family and the money to stay with them in hospital receive care. I saw a man lying by the toilet on a black plastic bin bag. He had been found in a market in Kampala, unconscious. They didn’t know anything about him, but thought he had diabetes, and they were waiting for him to die. He was lying in a pool of urine, and the flesh on his back was rotten because he couldn’t move. He was just rotting away.

What did you do?

Back at the hospice, I spoke to my mentor. She said that, even if someone is going to die, they can die clean and cared for. So the next day, I found a nurse who’d been trained in palliative care to help me, and we washed him. I brought him some clean sheets, and we asked the doctors and nurses to treat him. We tried to give him food and drink. I did that for five days, and when I came back on the sixth day, he’d died. He was lying on the floor, naked. The porter came with a trolley with a dead woman. He put his body on top of hers, and said they’d go to a mass grave together.

That was a big turning point in my life. It seemed that his life had no value at all — alive or dead. He was treated like an animal, like rubbish. I saw a risk of valuing others not for our shared humanity but for how much money they earn, the job title they have, the kind of house they live in, and the letters they have after their name.

Seems like it’s safe to say this confrontation with inequality and injustice was deeply affecting. How did you get involved with prisoners in Kampala?

I spent three months caring for patients at that hospital, and it turned out a lot of them were prisoners. I started learning how difficult life could be; they simply did not have access to justice as I understood it. So I asked if I could visit Luzira Upper Prison Uganda, a maximum-security prison. It was another life-changing moment.

What did you find there?

I visited the prison hospital. An 18-year-old boy had just died, and he was sewn into a blanket to be buried. The place was gray and dark and smelly and miserable. I thought that no one deserved to die in this kind of environment. While I’d felt the same way at the government hospital, I didn’t feel there was any possibility to make a difference in such a huge place, whereas the prison hospital only had about 70 beds.

So I returned to the UK for a couple of weeks, and with family, friends, my church and my old school, I raised about £5,000. I went back to Kampala and visited every hotel, asking for mattresses, blankets and sheets. I asked paint companies for paint. I worked with the prisoners and prison staff to do the refurbishment, putting in windows and lights and solar panels, so even if prisoners were going to die, they would die in a dignified and hopeful environment. At our opening ceremony, the Condemned Choir, a choir of death-row inmates, performed.

How do you manage to gain access to such institutions — and negotiate the bureaucracy and red tape that surely pervades them?

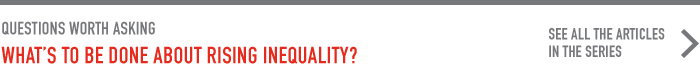

To begin with, we had to use bulldozer diplomacy. For instance, we had permission from the Commissioner of Prisons to establish a library in the maximum-security prison in Kenya, but in the prison, the officer in charge wasn’t so receptive. We’d wait hours to be shown into his office, and he’d read the newspaper. We’d sit in silence, for maybe an hour, and he’d send us home. Every day, the same thing. We got there earlier and earlier in the morning to show we wouldn’t give up. It didn’t work.

Eventually, we noticed that the Archbishop of Kenya’s office was near the prison headquarters. We had no connection to him in any way, but we managed to see him, and told him about our problem. He got a chauffeur to drive him to see the Commissioner of Prisons. We got access after that.

Lawyers can give a voice to those who are otherwise silenced. they can make society more just, and save lives.

You’re a lawyer and a magistrate in the United Kingdom. How did you bring this background into your work in Africa?

It’s not only in Africa that the people who come to court are often the poorest and most vulnerable in society. Whether you’re in a very wealthy country like the UK or in a poorer country like Uganda, Kenya or Sierra Leone, it’s always bewildering to come into conflict with the criminal justice system, and the power it has over individuals is huge. I came to realize that lawyers could give a voice to those who are otherwise silenced. They can make society more just, and save lives. They have the potential to free someone from the death penalty, or keep someone from having their children taken away from them, or from losing their house. Lawyers defend our most fundamental, basic rights.

So what was your approach in Africa?

In the UK, we take it for granted that one has access to legal representation. If someone doesn’t have a lawyer and is facing prison, the court appoints one, or at least the court clerk explains everything, and helps them through the process. In Uganda and other sub-Saharan African countries, 80% of prisoners never meet a lawyer. In countries where many people are illiterate, courts are often conducted in English, but in Uganda, for instance, maybe 50 different languages are spoken. The environment is totally alien to the average person being taken from a village to the police station and then to court. It is just a bewildering, overwhelming system.

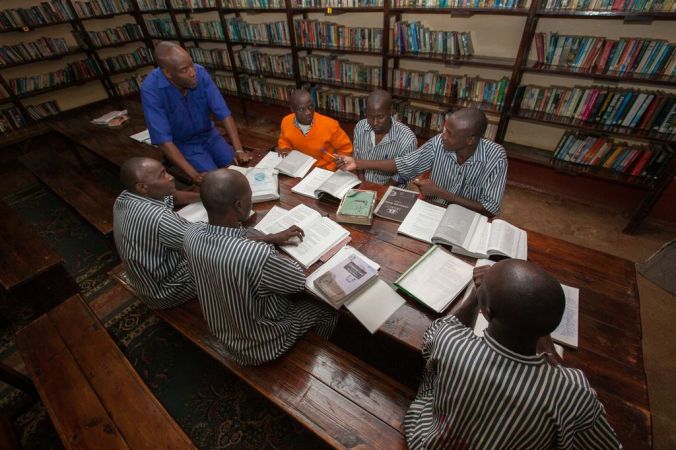

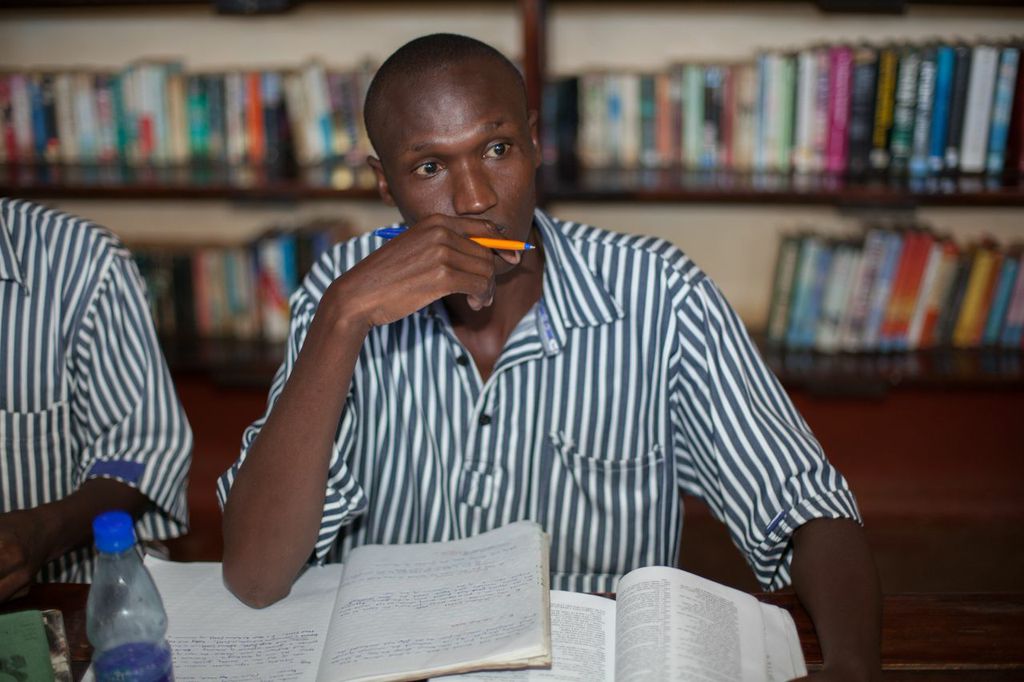

I wondered what would happen if we offered prisoners the chance to study for a legal qualification with a leading university — combined with support from local lawyers. It might help inmates navigate their own cases and those of their peers. I knew a distance course was possible, as I’d studied for my masters with the University of London while based in Kampala. So in 2011, we took applications from prisoners in Uganda to study law at the University of London. From one maximum-security prison, we had more than 150 applicants and took on nine students. Now we have a total of 16 students; this summer, we expect five of our students to graduate with diplomas in law.

justice is something we should all be able to engage with. It shouldn’t be the preserve of a particular class or something that is just done to people.

What do you hope to achieve by helping these prisoners get a legal education?

I sensed the good that could come from giving more vulnerable people in society training and support. I thought it could shake things up in societies where it tends to be wealthy people who become lawyers, and poor people who become prisoners. When people think about human rights and access to justice, it’s usually about making sure everyone has access to a lawyer. But justice is something we should all be able to engage with. It shouldn’t be the preserve of a particular class or something that is just done to people.

How are your students working out?

Three of our students have been instrumental in getting their own death sentences overturned, and a number of them have been released from prison. A soldier who was released was taken back by the Ugandan army, and they even gave him study leave to complete his law degree. He’s still working on it, but he’s already sitting in Ugandan military courts, helping to make decisions about how soldiers in those courts are dealt with.

Susan, our only female student, played a role in getting her own death sentence overturned a few months after starting her legal studies. She’s our best-performing student, nearly attaining a first-class result in the human rights module. She’ll be released from prison in early 2016, at which point she wants to become a trust lawyer. When it comes to issues of trusts and succession, women and children often suffer. When a husband dies, often his relatives come and take the land, property and possessions, and women and their children are left with nothing. Trust law can help empower people when it comes to gender inequality and matters of succession.

We’ve got to be very careful not to write people off as being inhuman. All of us have the potential to do tremendous bad and tremendous good.

What’s next for the African Prisons Project?

Besides trying to expand the number of prisoners who receive distance learning, we also train prison staff in basic legal knowledge and human rights. With this, they can help prisoners access bail, explain how trials in the magistrate court work, and so on. In an environment where so few people have legal knowledge, even just starting to understand the basics of law is a huge asset.

At one prison in Northern Uganda, three prison staff we trained helped to release 40 prisoners on bail within three months. That’s 40 people the prison won’t have to feed and who can go back to their families. Imagine the impact it could have if every single prison warden in a Ugandan prison were given this legal training.

Big picture, this is a challenge to all of us to make the best of whatever we have available in life. Our students’ resources are very limited — some of them study without the Internet, electricity or adequate sanitation — but their determination, commitment and ambition allow them to do remarkable things. Someone can come to prison totally illiterate and leave with letters after their name. They can go back to their families and their community, and say that prison added value to their life.

Do you believe that there’s a place for prisons, and do you believe that there’s a place for the death penalty?

I don’t believe there’s a place for the death penalty at all. We can never have a system that works fairly to ensure that decisions about who gets the death penalty are never arbitrary or wrong. We’ve got to be very careful not to write people off as being inhuman. All of us have the potential to do tremendous bad and tremendous good. Just because someone’s stolen something doesn’t mean they’ll always be a thief.

But I do think there is a place for prisons. Society needs to be protected from those who are dangerous and violent. Maybe I’m idealistic about the transformative potential of prison, but I’ve seen firsthand that they are places where people can be changed. And regardless of what I think, I don’t see any society moving away from them. So long as there are people in prison today, we need to think about what’s happening there and why, and how we serve those people.