The Vikings described a place called Vinland — a “land of wine,” bursting with berries. But where, exactly, was it? Space archeologist Sarah Parcak shares a step-by-step look at how her team used Norse texts and satellite imagery to search in eastern Canada.

Vinland. It means, quite literally, “wine land.” In their sagas, the Vikings described this place as warm enough to grow grain and grapes for wine. But where was this fabled Vinland? Many scholars have suggested it’s somewhere in North America. See, as the Vikings sailed from Greenland, they wrote about each parcel of land they encountered. For instance, they described an area with lots of rocks and miles of beaches that sounds like modern-day Labrador, the northern edge of Canada. The question is: How far south did they go?

In the 1960s, husband-and-wife adventurers the Ingstads followed the Vikings’ descriptions (much as archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann used the Iliad and Odyssey to locate ancient Troy) to rediscover an ancient site on the tip of the island of Newfoundland called L’Anse aux Meadows. This site dates back to 1000 AD, and is so far the only confirmed Norse settlement in North America. However, its discovery didn’t end the debate on where Vinland might be — it ignited it anew. The debate continues today. While most scholars accept that Vinland was likely on the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, we haven’t yet found the solid archaeological evidence to confirm that idea.

For the past 50 years, people have scoured the province of Newfoundland and Labrador — even looking as far south as New England — for Viking sites. They’ve advanced many notions, some outlandish — like that the Vikings reached Minnesota. However, no one had looked in a systematic, scientific way using new technologies to find potential Viking sites. This is what my team did. We scanned the entire eastern coastline of Canada using satellite imagery. Here’s a look at our process, and what we found.

- The key to the hunt: good research and enormous skepticism. My team and I started the search with one hypothesis: that we wouldn’t find anything Norse. When you’re looking at eastern Canada, there are two types of sites you’re much more likely to find: an indigenous site, built by one of the many native North American cultures that lived here, like the Inuit, the Dorset and Paleo-Eskimos, for starters. You’re also likely to find a historic site, built by European settlers in the mid to late 1700s. Before even looking at the satellite data, our team researched how each of these types of sites express themselves in the landscape. We got a sense of their typical size, shape and architectural configurations. At the same time, we read hundreds of articles on Norse settlements and studied satellite imagery for known Norse sites in other parts of the world to understand what they look like. We assumed that the bulk of anything we’d find using satellite imagery would be either historic or indigenous. If we’d gone in assuming we’d find something Norse, we would have had a confirmation bias as we did our analyses. We wanted the results to speak for themselves.

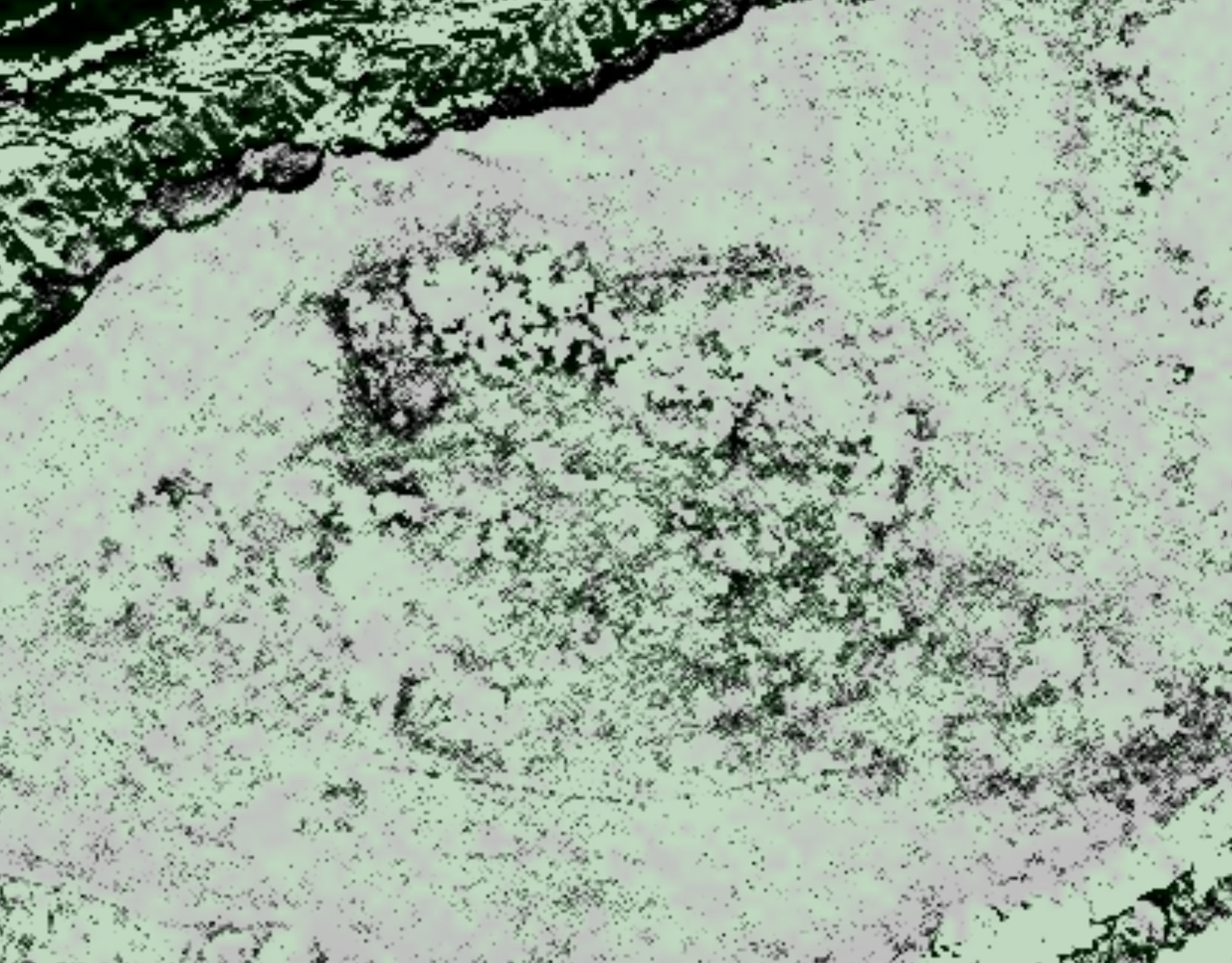

. - We started with Google Earth to identify areas of interest. Capturing data for all of eastern Canada would have cost tens of millions of dollars, so we started our search in Google Earth to scan for anomalies in vegetation health, looking for circular or rectangular formations that wouldn’t occur naturally and that might match the patterns of historic, indigenous or Norse settlement structures. We identified 50 areas of interest that way. Google Earth imagery has a resolution of about 50 to 60 centimeters per pixel — which is good, but we needed more detail. So we ordered high-resolution aerial photography for the 50 areas we selected, with a resolution of under 10 inches, or 25 centimeters, per pixel — so we could see things as small as a laptop screen. That, in turn, helped us narrow our search to down to just three sites. From there, we got high-resolution multi-spectral satellite imagery that let us see chemical signatures on the ground below. This final step helped us identify the two most promising sites.

Satellite imagery with .5m resolution shows the anomalies the team spotted from space. The darker areas hinted at the potential for turf structures, indicated by differences in the health of the vegetation on the surface. Image courtesy DigitalGlobe. - From there, we went in on the ground. A year and half ago, a team of two went out to do initial ground-based survey work at the two sites we’d identified. One seemed problematic, but the other site — located far south of L’Anse aux Meadows — seemed promising based on our readings. We planned a dig for June 2015. We had a six-person team co-directed by Gregory Mumford, my husband and archaeology partner, and Frederick Schwarz, an expert with more than 30 years of experience working in eastern Canada who would be able to tell us immediately if we had a historic or indigenous site. On the dig, we found a hearth and probable turf walls — not typical structures for indigenous or historic cultures (at least not outside the Arctic). Frederick told us, “I don’t know what I’m digging anymore.” He’d never seen anything like it — it was completely unfamiliar.

Peeling back the upper layer of grass reveals the southern edge of a potential turf feature, photographed on June 19, 2015. Photo: Greg Mumford. - We let the materials tell the story. Our expert told us, “If this is an indigenous North American site, it’ll have flint. If it’s historic European, you’re going to be able to fill buckets with ceramics.” We didn’t find either, even as we dug testing trenches in multiple spots. The absence of flint and ceramic isn’t conclusive, but we should have found them. Meanwhile, the Vikings needed a lot of iron for their farming equipment and ships. Iron production was a major part of their culture — it’s no coincidence that one of their important gods, Thor, was a master smith. The Vikings wouldn’t have settled anywhere where they didn’t have a good source of bog iron, a favorite raw material. Bog iron gathers at the base of roots in swamps; it’s rusty and crumbly until you roast off the impurities and smelt it down. As we excavated our site, we found 18 pounds of a glassy, blackened material, which we had analyzed by a Norse-metallurgy expert. As it turns out, the material is evidence of bog iron roasting, the first phase in Norse iron production. No indigenous groups worked metal in Newfoundland. Neither did any known historic groups.

This odd lump may be evidence of roasted bog iron, a characteristically Norse practice. Selected samples were analyzed by Dr. Thomas Birch, an expert in early metals, and microscopist Dr. John Still. Photo: Greg Mumford - And we’re planning for future work. The site we found, called Point Rosee, would have been a good place to settle. It has streams for fresh water and a nearby beach for fishing — not to mention a landing area for ships. Beyond that, the site is close to the only valley in Newfoundland warm enough for agriculture. Could this site have been a Norse settlement? The bog iron processing certainly suggests it’s a possibility. Right now, all we know for sure is that the site doesn’t match other known cultures in the area; the only culture it matches at present is Norse. Still, we have a lot of work to do before I’m comfortable calling it a Norse site. The site appears to be bigger than our first survey suggested, so it will take multiple seasons of excavation to understand this site’s specific purpose and function. As of now, we don’t know if we’ve found a site in what the Norse people called Vinland. This, however, we can say for sure: New technologies offer new approaches in the search for lost ancient sites. That’s an exciting start.

.

Sarah Parcak is the winner of the 2016 TED Prize. With the $1 million award, she’s built a citizen science platform called GlobalXplorer that allows anyone to join the search for archaeological sites. DigitalGlobe has provided satellite imagery; National Geographic Society has contributed rich content; and you’ll provide the analytical power.

Check out the Nova special “Vikings Unearthed,” for more on Parcak’s search for Norse sites.