I am often asked, “What inspires you?” and “When you have a creative block, how do you unblock it?” The unhelpful answer to the first question is that I can be inspired by just about everything, both good and bad. But when you have a problem to solve — whether it’s fixing a leak, keeping deer out of your yard, or trying to mend a broken relationship — your inspiration, your first clue about what to do, lies within an analysis of the problem itself. That’s where the solution originates.

As for a creative block, my psychic Drano, so to speak, is my environment and the things and people in it. I am lucky enough to live and work in Manhattan, and when I’m stuck, I have only to talk two or three blocks in any direction and I’m instantly reminded of the resilience of humanity and our ability to create things in the face of massive indifference and mounting expense. You see examples of design that astound (MoMA, the Chrysler Building, Central Park), some that are a disaster (subway passages that are too small to handle commuter crowds, taxi off-duty lights, poorly demarked sidewalks suddenly closed for construction), and everything in between.

But you don’t need to be a New Yorker or a designer to appreciate how things are created and how they function in the world. You just have to be interested. And yes, you have to judge, often based on a first impression. Why not learn how to do it better? Here are some examples of objects and places that form my ideas about design and how it can work, or not. I encounter them in my life every day. Let’s start with one that’s very simple and often overlooked:

1. Help me organize my life, please

If you work in publishing, you will have discovered binder clips very quickly. They hold literally everything together, from manuscripts to page proofs, and I’ve found them to be an invaluable organizational tool.

If you work in publishing, you will have discovered binder clips very quickly. They hold literally everything together, from manuscripts to page proofs, and I’ve found them to be an invaluable organizational tool.

For those of you who don’t work in publishing, I urge you to get some binder clips regardless. The simplicity and elegance of these devices is utterly transparent, as opposed to say, digital folders within folders within folders. And the handles of the clip can be collapsed down so that they lie flat.

Whenever I go on a trip (once a month on average), I print out all applicable documents — boarding passes, itineraries, hotel reservation codes, rental car papers, etc. — and collect them in a single bundle with a color-coded binder clip. I drop the bundle in my tote bag (with the clip visible at the top — this is very important) and I’m off. When I need the documents, they can be located immediately by the bright hue of the clip.

As for storing all of this stuff on your phone, news flash: your phone can die. Paper does not die, because it’s already dead and resurrected. I remember being caught in a security at JFK behind a gentleman (ahem) who was trying in vain to revive his smartphone to show his boarding pass, to no avail. There were tears.

First impression: Squeeze, clamp, release. Organized.

2. Nice package

As long as there are consumer goods, there will always be physical packaging. But just because something is meant to be paid for and consumed does not mean its design has to be cloying, condescending, or screaming for your attention. The Mrs. Meyer’s cleaning products are a great recent example of how this can be done distinctively and successfully. The typography is so, well, clean. The red circle with the white interior is strategically placed in the center of the label, clearly telling you what it smells like. The product itself is biodegradable and isn’t tested on animals. The bottles are recyclable.

First impression: I can identify this immediately, and a great product will keep me a return customer.

3. Bite.

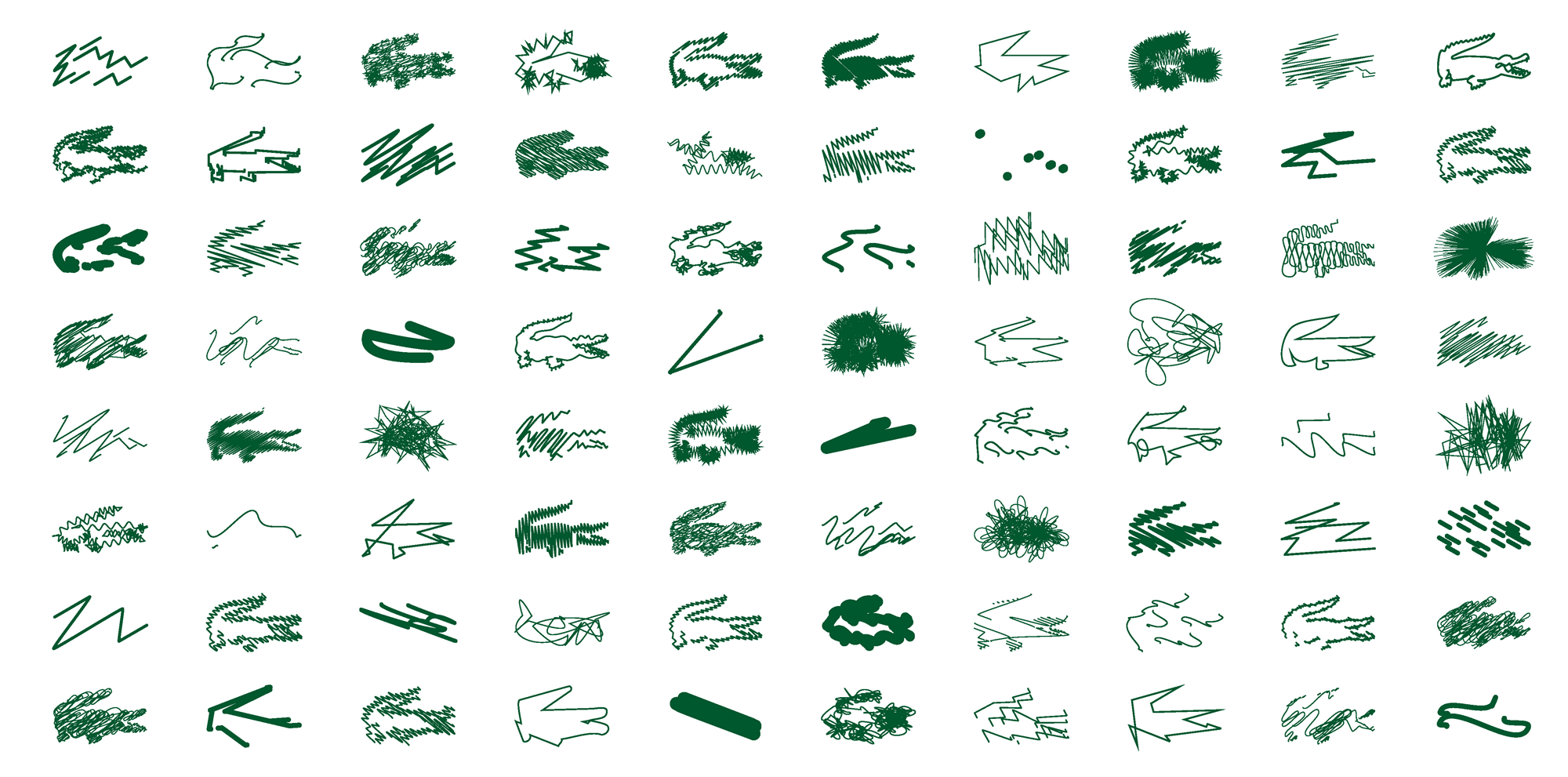

When I heard that one of my graphic-design heroes, Peter Saville — the legendary designer for Manchester, England, label Factory Records (whose recording artists included Joy Division and New Order) — was going to redesign the iconic Lacoste crocodile (below), I was as surprised as I was delighted. Here were two of my favorite worlds — preppy clothes and post-punk music — colliding unexpectedly and deliriously head-on.

The original logo was created in the 1920s by French tennis star René Lacoste, nicknamed “The Crocodile” for his tenacity on the court. For its 2013 limited edition of the shirt, the Lacoste label hired Saville to reinterpret it, and he did so with inspired fervor. He generated eighty versions in all, commemorating the 80th anniversary of the company. These abstractions are recognizable because we know both the source material and the context: over the heart on a white cotton polo shirt.

First impression of the original logo: Cool metaphor.

First impression of Saville’s variations: Even cooler.

4. Fully adjustable.

You may or may not be familiar with this side table, but the designer, Eileen Gray (1878-1976), deserves to be a household name. She is my go-to design hero for furniture and interiors, and she came to prominence after her death. Gray befriended contemporaries like Le Corbusier and Marcel Breuer, and her work was inspired by the Bauhaus, but I think she transcended that movement with just the right amount of quirk.

You may or may not be familiar with this side table, but the designer, Eileen Gray (1878-1976), deserves to be a household name. She is my go-to design hero for furniture and interiors, and she came to prominence after her death. Gray befriended contemporaries like Le Corbusier and Marcel Breuer, and her work was inspired by the Bauhaus, but I think she transcended that movement with just the right amount of quirk.

She was recognized by clients and the design cognoscenti of her milieu, but none of her creations were mass-produced in her lifetime, which is tragic, and she faded into obscurity after World War II. But interest in her achievements was revived in 1972 by fashion designer Yves St. Laurent, who bought some of her work at auction. In 2009, Gray’s “Dragons” armchair prototype (ca.1919) sold for more than $28 million, setting a record for twentieth-century furniture that has yet to be surpassed.

The E1027 table (shown), named after the seaside house she built in the south of France with her partner, Jean Badovici, is beautiful, functional, and affordable. This faithful reproduction is widely available now for around $99. It looks great, but the point is that it derives its form from its function: you can slide the base under your bed so that the glass top floats over your lap. The height can be adjusted via the attached key and notched chrome stem.

First impression: To quote the early-twentieth-century monologist Ruth Draper: “It’s chrome and glass and steel. It’s adorable.”

5. Counting down …

I am a habitually fast walker (because I’m always late, but that’s another story), so when these crossing signals with countdown clocks started to appear at some Midtown Manhattan intersections in 2010, I was thrilled. They take all the guesswork out of deciding whether to try to beat the light or cool your heels at the curb.

It’s not that the old system was bad, but this change makes a huge difference. Basically, when you see the white-lit walking figure (not pictured), it’s okay to cross. Then, a red-lit hand appears next to the number 20, which then counts down to zero (previously, there were no numbers). So, the image here (taken outside my apartment building) means that you now have 12 seconds left (and counting) to cross the street before you get run over. Or, stay put and wait for the walking man again. That’s the kind of clarity I need.

Of course, real New Yorkers know that even when the countdown runs out you still have about five seconds to get across, but I probably shouldn’t say that. Also, the “rule of physics” traffic law always applies to crossing the streets of New York City — that is, if there are no cars coming, go for it, regardless of what the light indicates. I shouldn’t say that, either.

First impression: 12 seconds to cross the street? An eternity. I can do that.

6. Lead us not into Penn Station.

Certainly one of the most egregious New York design crimes of the last century was the destruction of the original Pennsylvania Station in 1962, and its replacement with the abysmal drop-ceilinged, overhead-fluorescent-lit, basement-level hell-pit under Madison Square Garden that remains today. It still somehow functions as the most-used transit hub in the United States, with more than 600,000 travelers moving in and out each day, at the rate of 1,000 people every 90 seconds. And yet it’s an embarrassment of confusion and squalor, especially for a city that claims the mantle of Capital of the World (and yes, I use Penn Station all the time; I have to — I’m always on Amtrak).

In what appears to be a cruel joke, there are photos mounted on the gate pillars showing how spectacular the original vaulted Beaux Arts building used to be. Thanks a lot. But the mystery here is not only why it is so ugly, but how difficult it is to navigate through.

First impression: Airless, scuzzy, inefficient. A terrible introduction for visitors to New York City.

7. How refreshing.

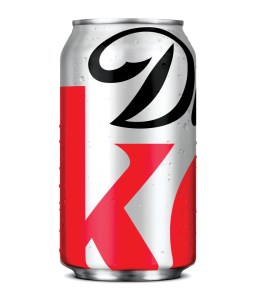

This redesign of the Diet Coke can is mysterious in the best possible way. Besides being formally striking, it assumes a level of intelligence and sophistication in its audience that is truly commendable, drawing on the “Less Is More” principles espoused by the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The visual vocabulary of the brand is reduced to its most essential parts, and we understand immediately what we’re looking at, based on very little verbal information.

This redesign of the Diet Coke can is mysterious in the best possible way. Besides being formally striking, it assumes a level of intelligence and sophistication in its audience that is truly commendable, drawing on the “Less Is More” principles espoused by the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The visual vocabulary of the brand is reduced to its most essential parts, and we understand immediately what we’re looking at, based on very little verbal information.

This is made possible by our decades-long familiarity with the logotype of the product and its application to a soda can. It’s a cherished friend in fabulous new clothes, a BFF’s makeover that you thought never could or would happen.

Truly great packaging.

First impression: Instantly recognizable; I don’t even need to be able to read it. Thank you for trusting me.

Judge This by Chip Kidd (TED Books/Simon & Schuster) is available now. Watch Chip’s talk: Designing books is no laughing matter. Ok, it is.