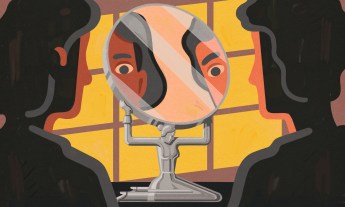

Like it or not, charisma matters when it comes to leadership. But we should be aware of the power that persuasion can have on us, says business school professor and researcher Jochen Menges.

Winston Churchill had it — but so did Eva Perón. Nelson Mandela had it — as did Adolf Hitler. Charisma is a force that can rally people during difficult times, but it can also blind people and lead them to accept unwise actions, policies or conditions. And when it comes to leadership, political and professional, charisma matters more than we’d probably like to admit.

It’s long been thought that charismatic leaders inspire their followers or, at least, stir up their emotions. But Jochen Menges, a German-born researcher on leadership and a faculty member at Cambridge’s Judge Business School in the UK, was driven to get a more detailed understanding of charisma’s impact on people (TEDxUHasselt Talk: Awestruck: Surprising facts about why we fall for charismatic leaders). In July 2008, he went to see then-presidential candidate Barack Obama address an audience of 200,000 in Berlin. Menges recalls feeling “warm inside” and “mesmerized.” When he scanned the crowd, “I was expecting to see lots of positive emotions, but people showed none,” he says. “They were just frozen.” The experience led him to embark on a series of studies.

In background research, Menges found that charisma was often viewed as a positive force. “What was missing was a critical angle,” he says. “And much of the research on emotional expressiveness has focused mostly on the leaders rather than on followers.” In one of the studies he conducted, university students were asked to recall and then write about either a charismatic leader or a general leader. After writing, they were shown movie clips while their facial expressions were recorded. One group was shown a positive video of a couple reuniting, and another group was shown a negative video of a couple losing a friend. Afterward, the participants’ faces were filmed while they were told to display a few different emotions: neutral, happy and sad. “People who had been primed with thinking of a charismatic leader exhibited less emotion while watching the clip,” regardless of whether they saw the positive or negative video, says Menges.

In another study, university students were asked to read and respond to workplace scenarios. They were told that they had been working at a company for six months and the participants had one of these kinds of bosses: high charisma, low charisma, high individualized consideration (warm, friendly), or low individualized consideration. (The terms “charisma” and “individualized consideration” were not used in the descriptions given to study participants, so as not to bias them.) In the scenario, they were told they were given responsibility for a demanding, high-profile project, and after months of hard work, they presented their ideas to higher-ups. At this point, participants were told they got either a positive outcome (“your project is so interesting to the senior management that you have been invited to a workshop next week…”) or negative outcome (“your project will not receive any further support from senior management…”). Finally, the subjects filled out an Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), a psychological evaluation tool used to assess the degree to which a person suppresses their emotions. Subjects who had a high-charisma boss significantly suppressed their emotional reactions; whether they experienced a positive or negative outcome had no impact, according to Menges. In other words, even a fictional charismatic presence, it seems, appears to inhibit someone’s emotional range.

Why does suppressing emotions matter? Some studies have shown “emotion suppression absorbs mental resources, deteriorates cognitive performance and impacts memory,” according to Menges. When a person is engaged in emotion suppression, they appear to be less able to make critical decisions, leaving them more vulnerable to individuals who have power. As a result of his findings from these two studies and one other, Menges has called this impact “the awestruck effect.” But he believes that charisma as a dominant, assertive behavior is successful only when it’s matched by submissive behavior on the part of a leader’s followers.

Of course, not all charismatic leaders are intent on manipulating people, cautions Menges. Take Nelson Mandela or Gloria Steinem, for example. “These kinds of leaders have been important when society needs to make a change,” he says. However, “if you want followers to contribute and participate, what you may need to do is distribute your message not only through speeches but through other forms.” This could include newsletters, articles or interviews, formats in which people have the distance and ability to offer a more critical assessment.

More important, we followers need to stay clear-headed. We should also realize that during certain situations, like economic crises or periods of social instability, we can be more prone to influence, so we should be on our guard when those times arrive. Keeping ourselves from falling for a charismatic leader is “tough,” Menges concedes. “But our task is to remind ourselves that he or she is an ordinary human being.”