Terrorists make headlines by destroying ancient sites like Palmyra, in Syria. But there’s an even more sinister endgame, as archaeologist and TED Prize winner Sarah Parcak explains.

You’ve probably heard of blood diamonds and blood ivory. But what about blood antiquities?

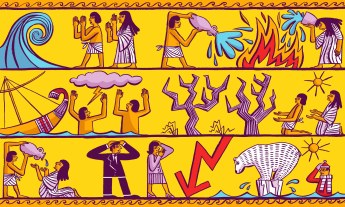

Over the past two decades, fundamentalist groups have discovered that they can get global attention by destroying irreplaceable ancient sites. The Taliban set dynamite to the standing Buddhas at Bamiyan in 2001, and now the Islamic State (ISIL) is deliberately destroying the 2,000-year-old city of Palmyra, in Syria. ISIL is all about shock value, and its leaders are laying waste to this symbol of diplomacy and culture piece by piece, so much so that you can actually predict what they’re likely to destroy next.

As a satellite archaeologist, I know this because I have been watching. I am part of a network of people monitoring what’s happening at ancient sites in Iraq and Syria — from space. We can see clearly the destruction. We can also see something else just as important that they are doing much more quietly: they are renting out the land on which archaeological sites sit to people who appear to be professional looters in order to sell priceless antiquities for profit.

‘ISIL has encouraged the looting of archaeological sites for two purposes: making money and erasing the cultural heritage of Iraq and Syria.’

There are real reasons we should all care about both the destruction and the plunder. As Andrew Keller, the co-lead for the US government’s efforts to counter ISIL’s finances, noted in September 2015: “ISIL has encouraged the looting of archaeological sites for two purposes: making money and erasing the cultural heritage of Iraq and Syria.” That’s why the FBI alerted art collectors and dealers in August that artifacts taken by ISIL are entering the marketplace. In May, US Special Operations Forces raided the compound of an ISIL finance chief and found a stockpile of historical objects. That finance chief is described as the head of “ISIL’s oil and gas, and antiquities division.” Think about that: the same person within ISIL is in charge of revenue from oil — an obvious money-maker — and antiquities. Looting is systematic, controlled — and of great strategic importance to a terrorist organization.

Keller estimates that as many as 5,000 archeological sites sit in territory ISIL controls, and that the group has earned several million dollars from antiquities sales since the middle of 2014. But when you use satellite imagery to map these areas, it’s clear that thousands of archeological sites in the region haven’t been mapped or surveyed yet. There is still so much we just don’t know.

We have no idea of the value of what’s being taken. We don’t know how the money flows. Documents suggest ISIL is collecting a 20 percent “khums” or sales tax on the proceeds of looting — but we just don’t know exactly. And we don’t know the extent of the networks involved. We suspect that the sale of antiquities is connected to gun running, drug and human trafficking, and that they are potentially following the same routes to black markets in the East and West. But we don’t know which criminal elements are involved.

In archaeology, context is everything. Objects allow us to reconstruct the past. Taking artifacts from a temple or an ancient private house is like emptying out a time capsule. We’ll eventually get the box, with nothing inside. Looting has an immense impact on our ability to understand our global cultural heritage; once these objects are gone, so too is our chance of piecing together humanity’s shared story.

We need to spread the word that the purchase of blood antiquities supports criminal networks.

Of course, looting has always happened. The pyramids in ancient Egypt were looted not long after they were officially sealed, 4,500 years ago. Looting speaks to a lack of economic opportunities — frankly, we all would loot too if our families’ continued survival depended on it. It’s not something we can fully stop, but it’s something we must take action to lessen.

Ultimately, we need to shut down the markets for blood antiquities. There are many places to buy antiquities legally: online marketplaces where you can get cylinder seals from Mesopotamia for a couple hundred dollars, or auction houses where you can buy a cache of cuneiform tablets for $200,000. But objects coming from Syria, Iraq and other parts of the Middle East right now may well be looted. (The owner of the US-based arts and crafts chain store Hobby Lobby, for example, is under investigation for buying “illicit artifacts” from this region.) We need to spread the word and let collectors know that, just as it does with blood diamonds or blood ivory, the purchase of blood antiquities supports criminal networks.

Back in the 1950s, people loved fur. Now, very few people wear it. If we can raise awareness of the ethical issues involved in buying antiquities, we can find ways for everyone to be a part of understanding our shared history. The past should be in our hearts, not on our shelves, and we should all be mindful of the true impact of looting, which affects us all, whether we know it or not.

.

With the 2016 TED Prize, Sarah Parcak has built a citizen science platform for archaeology, called GlobalXplorer, that invites the world to help locate and protect ancient sites. DigitalGlobe has provided satellite imagery; National Geographic Society has contributed rich content and exploration support; and you’ll provide the analytical power.

Photo of The Temple of Bel in Palmyra, Syria, by iStock.